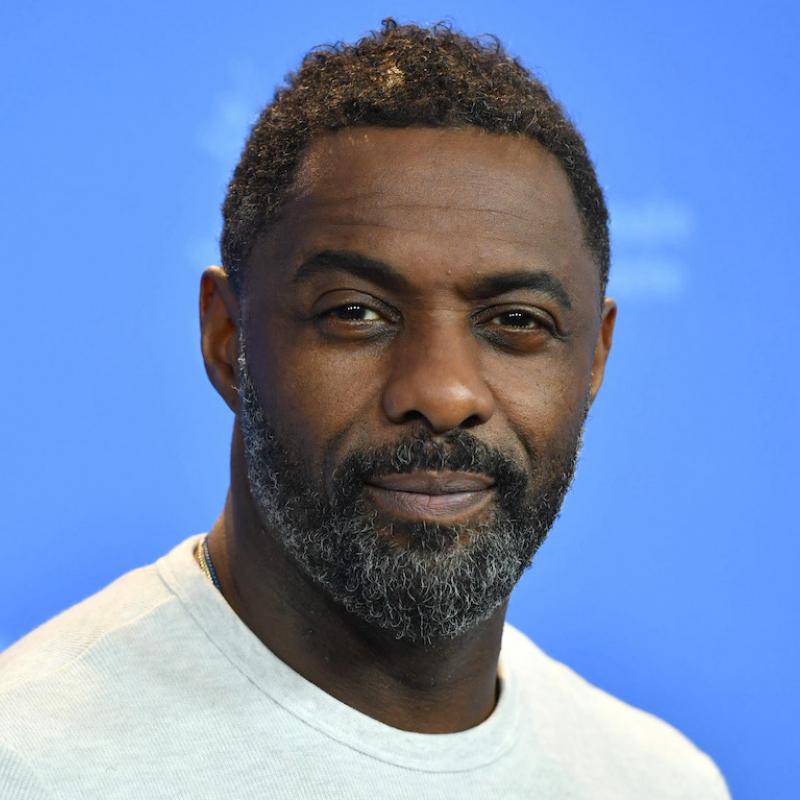

Clark Johnson, On Screen and Behind the Scenes

Clark Johnson has worked as a director on several of TV's most memorable cop shows, including The Shield, Homicide: Life on the Street and the pilot episode of the critically acclaimed HBO series The Wire. This season, he's appearing on camera as well, as The Wire's City Editor Gus Haynes.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on January 21, 2008

Transcript

DATE January 21, 2008 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Clark Johnson, actor and director for "The Wire," on

"The Wire," "The Shield," "Homicide," directing and his life

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

We're big fans of the HBO series "The Wire" so we have a "Wire" double-header.

Tomorrow we'll hear from the actor who plays Omar, Michael K. Williams. My

guest today is Clark Johnson. He directed the pilot of "The Wire," the second

episode, and the series finale, which will shown in a few weeks. And on this

fifth and final season, he's also on camera as Gus Haynes, the city editor of

The Baltimore Sun. Johnson also directed the pilot and several other episodes

of the FX cop series "The Shield," including the series finale, which has not

yet been shown.

Many of us first saw Johnson in the '90s on the TV series "Homicide," playing

Detected Meldrick Lewis. "Homicide" was based on a book by David Simon, who

later created "The Wire" which, like "Homicide," is set in Baltimore. Simon

has described "The Wire" as really about the American city and how we live and

about how institutions affect the individuals within them and the compromises

those individuals are often forced to make. In this final season, Simon has

added a new institution, the newspaper, specifically a fictionalized version

of The Baltimore Sun, where Simon used to work. Clark Johnson as Gus Haynes,

the city editor, is upholding journalistic values that the editors above him

seem willing to compromise. They want colorful stories that will get

attention, even if the facts don't quite check out.

In this scene, Gus is talking to a reporter named Scott Templeton, who was

assigned to write a color story about the Orioles game. The story he's handed

in is about a 13-year-old African-American boy who's in a wheelchair because a

stray bullet left him paralyzed. The kid wants to see the game, but can't

afford to buy a scalped ticket. The reporter says he only knows the kid's

nickname, no full name, no photo. Gus, the editor, expresses his skepticism

to the reporter. Later in the scene, the managing editor intervenes.

(Soundbite of "The Wire")

Mr. CLARK JOHNSON: (As Gus Haynes) The kid is nowhere to be found. I sent

photo down there to try to dig him up. Nothing. Probably left. OK, so we

got a poor black kid, in a wheelchair, with no ticket. He rolls himself from

somewhere in west Baltimore to--to the shadow of the mighty brick-faced

coliseum known as Oriole Park, listening to the--the cheers from the crowd

which told the whole tale.

Unidentified Actor #1: (In character) I got a five.

Mr. JOHNSON: (as Gus Haynes) We're going to give good play to a 13-year-old

known only as E.J., who declines to give his name because he skipped school.

He's got no parents. He lives with his aunt. I mean, I'm not saying that

this kid isn't everything you say he is, but Scott, damn, as an editor, I need

a little more to go on if I'm going to fly this thing.

Mr. THOMAS McCARTHY: (As Scott Templeton) I resent the implication.

(Soundbite of phone ringing)

Mr. JOHNSON: (as Gus Haynes) I'm not implying anything. I'm on your side.

But the standard for us has to be...

Unidentified Actor #2: (as Jim) Scott, just finished your story. Good read.

I'm putting it out front. I think you've really captured the disparity of the

two worlds in this city in a highly readable narrative. I wouldn't change a

word.

Mr. McCARTHY: (as Scott Templeton) Thanks, but I'm not sure everyone shares

your enthusiasm.

Mr. JOHNSON: (as Gus Haynes) Jim, aren't you just a little bit concerned

that we don't even have a last name for this kid? I mean, I thought we held

ourselves up to a...

Actor #2: (as Jim) It's not an ideal situation, no, but the boy's reluctance

to give his last name clearly stems from his fear of being discovered as a

truant. Do you have a problem with it?

Mr. JOHNSON: (as Gus Haynes) A little bit, kind of, yeah. I'm just saying

that the standards we have...

Actor #2: (as Jim) I think we're on terra firma here.

Mr. JOHNSON: (as Gus Haynes) Gotcha. Man made a call. You're good to go.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Clark Johnson, welcome to FRESH AIR. Did you expect to get an acting

part on the show after having directed the first two episodes years ago?

Mr. JOHNSON: I hadn't really thought about it. I kept wanting to regain

contact with the show because, you know, after having done the pilot and the

first couple, I went off into feature film land and "The Shield" and things

elsewhere, so I couldn't get back. So I had hoped to do one of the ones in

the last season, and then the role came up and it was a regular role for the

season and I thought, what a better way to, you know, to finish this loop for

me, to be involved as an actor and a director.

GROSS: What did the creator of the show, David Simon, tell you about your

part as the city editor at the Baltimore Sun and about the problems that Simon

himself faced during the period of cutbacks and buyouts at the Baltimore Sun

when he worked there?

Mr. JOHNSON: Well, first of all, he let me know that the character was

loosely based on him and his experiences in a sense. And then Bill Zorzi, our

other former Sun reporter who is now a producer and a great writer for the

show claims that the character's loosely based on him so I took it from both

of them and that became the character.

GROSS: David Simon was a reporter, not an editor, right?

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah, yeah. He was a reporter, but the newspaper guy, you

know? It was the sensibility, the righteous indignation that comes out of my

dialogue comes from his take on the state of print journalism so...

GROSS: I'm a huge fan of "The Wire" but I didn't pick it up right away. I

found it hard at first to keep track of all the characters because there are

so many. You've got the cops, you've got the drug dealers, you've got the

city government that you're following, and when the characters were all being

introduced, I just couldn't keep track and I--it took me a couple of seasons

before I really went back and followed them. And I've actually heard this

from other people, too, that it was initially hard for them to follow

everything because there's so many characters to figure out early on. Now I

love these characters so much, but I'm wondering, when you started directing

it and you were doing the episode, seeing all these characters that you had to

establish in one hour, how did you handle that? Like, what were some of the

challenges for you?

Mr. JOHNSON: I think most of the characters were so well defined and so

creatively drawn that I didn't have a problem with it, with the pilot. Now

when I came back this season and had to reconnect, it was dense because, you

know, people had come and gone and people were referred to that weren't on the

show anymore, and it was pretty, you know, it was a lot of homework to get up

to speed. And I think that that's one of the things that people attribute our

so-called lack of a huge audience is that very thing, is that you got to work

at it. You've got to get in there and really get to know these people. It's

dense, and--but as you experienced, once you do, you're kind of hooked. And

that's why we have a great, passionately loyal fan base.

GROSS: That's why DVDs are so great, because you can always pick it up.

Mr. JOHNSON: Right.

GROSS: What were some of the guiding principles behind how the show was

supposed to look when you started directing it?

Mr. JOHNSON: Basically the show itself has two things. It has a look of its

own and that the place that it's set in is an important character. Now,

Baltimore was an important character in this series, and the look of the show

was quite different from the look of, say, "The Shield," which was frenetic

and handheld and run-and-gun 16 mil embedded type of a format, of a style,

whereas "The Wire," because of the theme of the show, which is to surveil and

to observe and to watch from a distance, we took the idea to do it with a long

lens and just to be more settled and to watch from afar, and that's been the

look of the show throughout, is that detached, you know, view of it.

GROSS: Have you learned a lot of street slang from doing "Homicide" and "The

Shield" and "The Wire"?

Mr. JOHNSON: Well, the language evolves, you know. The colorful thing about

any sublingo, if you want, is that it completely evolves. You can go all the

way to the streets of London where they have that Cockney slang, where that

bangers and mash means absolutely something else, and that would change and

morph into another phrase, so if you don't keep up with it, it becomes

irrelevant really quickly. It's fine for, you know, a TV show but it doesn't

really represent what the kids are speaking like now.

Like for instance, my daughter goes to school in Paris. She's in college in

Paris and they--she's learning colloquial French in addition to her great, you

know, school-taught French, and one of the phrases they use there is...(French

spoken) which means, `What up, homey?' in colloquial French. (French spoken).

So things change...

GROSS: But what does sit mean? I lost you.

Mr. JOHNSON: `What up, homey?'

GROSS: `What up, homey?' Oh, oh.

Mr. JOHNSON: (French spoken). And I mean, you know, so things change and,

you know, we try and to keep up with it. And David Simon has a great ear for

it and, you know, all those years on the beat, you know, as a, you know, just

a service reporter, he would collect those things and then, of course, he'd

have to update them. And the the kids that we hire on the show, a lot of

times come right off the street, so we tend to stay fairly current with that,

I think.

GROSS: So where does that leave you as a director when you're directing young

people who have some, like, instinctual talent but they're like not trained?

Mr. JOHNSON: Well, that instinctual talent is what I nurture and try to

bring out, whereas we had a lot of stunt casting with reporters or former

reporters from The Sun and people that Simon and Zorzi knew. And, you know, a

lot of them, God bless them, great writers but couldn't act worth a damn, you

know, so it was easier getting stuff out of the kids who were, you know, open

books, fresh, you know, takes on it than jaded hard-core reporters trying to

play themselves. Be funny because a lot of them are really charismatic and

interesting off camera. Soon as they say "Action!" they freeze up...

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. JOHNSON: ...whereas with the kids it didn't happen too often.

GROSS: So tell me what kind of advice you gave the kids?

Mr. JOHNSON: I didn't really--I don't give advice unless it's asked for,

generally. I mean, I just--what I do as a director is I--because I'm an

actor, I watch, and as I watch I'll tell the actor what I just saw, and if

that's not what the actor was trying to present, then we'll discuss it and

we'll say, `Well, how can we get that across? Because it looked to me like

you were doing this.' So that's--pretty much applies to the way I raise my

kids or the way I direct actors, you know. It's like, OK, here's what I saw.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Clark Johnson, and in the

current series of "The Wire" he plays Gus Haynes, who's the city editor at The

Baltimore Sun, and he also directed the first two episodes of "The Wire" and

directed the finale of "The Wire," which is coming up in just a few weeks. He

played Detective Meldrick Lewis on "Homicide," and also directed the pilot and

several other episodes of "The Shield."

In the first seasons, the gangs, the drug gangs are in high-rises and

low-rises of the housing projects.

Mr. JOHNSON: Right.

GROSS: And the low-rises, where the kids dealing the drugs stay is like on

the lawn in front of the low-rises and they're sitting on like beat-up easy

chairs and beat-up couches and kind it's of like their office on the lawn.

Was that a housing project that you were shooting in?

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah, that was. I mean, that couch actually--that's funny that

you remind me of that because it's been a while, but Bob Colesberry, it was, I

think it was his idea with that couch, because it was just this old mangy

couch and we thought, OK, it's an office. And that wouldn't be inappropriate.

I mean, kids, they're hanging out, and they're kids, I mean, that's the

tragedy of it. What would these kids be doing if they were channeling these

energies into something constructive other than drug dealing, which is often

the only option some of them feel that they have. So that was really

important for us to show them hiding in plain sight their activities.

The other complication in Baltimore was a lot of those towers came down, and

they were, you know, replaced with a more diverse housing situation that

supposedly, you know, it gives people a little more sense of pride than just

those impersonal high-rises. I remember in Philadelphia when I was a kid, the

towers in the Forties off of Market Street. I'm walking by there, because I'm

from West Philly, and my uncle said--he looked up at towers, he said, `They

just getting us ready for prison.' Because, you know, the chain-link fence

outside that marks the hallways that are outside the building. So this is

really relevant to us and to this story, that idea of future incarceration,

bleak as that may seem.

GROSS: My guest is Clark Johnson. He directed the first two episodes of "The

Wire" as well as the upcoming series finale. And on this finale season, he

places Gus Haynes, the city editor of The Baltimore Sun. We'll talk more

after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Clark Johnson. On this season of the HBO series "The

Wire" he plays Gus Haynes, the city editor of The Baltimore Sun. Johnson also

directed the pilot, the second episode and the upcoming series finale.

Were you around for the auditions for "The Wire"?

Mr. JOHNSON: For the pilot?

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. JOHNSON: Oh, absolutely. I mean, the director, that's my job is to be

with, you know, Alexa Fogel is our casting director, and her and myself and

Simon and Colesberry would have sessions and bring in hundreds of actors from

New York and LA and Baltimore. Dominic...(unintelligible)...came from London.

And then we'd take our primary choices out to HBO, and Carolyn Strauss and

Albrecht would look at them and then we'd make our decisions as to who got the

roles. But yeah, that's--casting to me is as important as anything there is

in a successful drama presentation.

GROSS: Can you tell us one of your favorite casting stories?

Mr. JOHNSON: I could, but it's visual, and it's "The Shield," you know? Do

you want to talk about "The Shield" for a second? Because it's the classic...

GROSS: Sure.

Mr. JOHNSON: ...audition tape of all times.

GROSS: Sure.

Mr. JOHNSON: Well, the opening in the pilot of "The Shield," Mike Chiklis

and his strike team are chasing this drug dealer through thick and thin, all

over the place, and this kid is swallowing his drugs and throwing stuff away

as they're chasing him, and they catch him finally when he gets to a fence

that he can't open, and he turns around and says, `You lose. You lose, G-man'

or something like that. And Chiklis, you know, punches him in the stomach,

yanks down his pants, and he's got his drugs--more drugs taped to his groin,

and Chiklis tears the tape off and the kid screams in agony and he

says--whatever his line is.

So we had this kid came in to audition, and he, you know, it's a standard

thing in the audition process. It's a bleak little room with a bunched couple

of chairs, and the director and the casting people are sitting there looking

at the poor actor who's standing at a piece of tape and he's reading to a

casting person off camera. And this kid came in and he said his name and what

role he was reading for, and we said `Action' and he took off running. He

left the room. We could hear his footsteps receding down the hall. We were

sitting there, we're so `What the hell's going on?'

And we kept rolling and then the kid--we could hear his footsteps getting

louder and he came back and he came back to his mark. He said his line, he

said Chiklis' line, he punched himself in the stomach, he pulled his own pants

down. The camera girl, God bless her, tilted down because we knew no one

would belive us, and there he was in all his glory. He had taped something--I

didn't look that closely--to his groin, and yanked it off himself. We panned

up and he finished the scene, and we just sat there just in rapt amazement at

just the energy and the great effort that this kid had done to play

everybody's role in the scene. And sadly he didn't get the part, but it was

the most remarkable...

GROSS: He didn't? After all that, he didn't get the part?

Mr. JOHNSON: Isn't that pathetic? No, he didn't.

GROSS: Why? Why not?

Mr. JOHNSON: Because there was an actor that was better. I mean, actors

live in a hard, harsh reality of `too tall, too short, too happy, too sad,'

you know. That was one of the problems of me being a director. I'm glad I

was an actor first because if I knew then what I know now, oh my God. It's

daunting how decisions are made.

GROSS: So is there anything that you started, in terms of a shooting style or

mood or whatever, when you started doing "The Wire" that you think really kind

of stuck and you can see that influence continuing now?

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah. The long lens look, and I actually got sick of it

after--no, I mean, it's, you know, "Homicide" was an amazing experience for me

because, you know, a young actor, I had done another cop show before that

called "Night Heat," and before that I was a driver, you know, in the movies.

And so the experience of "Homicide" and the way that show was shot just

completely stuck with me, you know. And oddly enough--and this is not just a

hindsight thing--at the time, because the camera was so frenetic and always in

places where you didn't expect it to be, it took a while for us actors to get

used to that conceit, and that was specific to that show. We predated "NYPD

Blue."

And so once "Homicide" became the cool look, you couldn't watch a Ford

commercial without seeing that same camera style. When "The Shield" came out

with--what we used--Ronn Schmidt and I had a real specific look to that show,

and a lot of it had to do with adjusting the shutter, the angle of the shutter

so it gives it sort of a choppy look that you can't quite pick up with your

eye. That was really specific for that show. And then you see it in

everything now, and you see the camera moving and being part of the other

actors' perspective, like if somebody's got something in his hand, we tilt

down and we tilt up. Now I see it everywhere.

Not that we're--you know, invented the wheel, it's just that once an idea

hits--and I've, you know, stolen from "Homicide," I'm not saying otherwise,

but once something becomes part of the popular mosaic, it gets tired really

quickly. When you have something that's really as ground breaking as the look

of "Homicide" or the look of "The Wire" or the look of "The Shield," it

becomes part of the mainstream and then, you know, anything like that, you

don't want to do it anymore because, OK, now everyone's doing it. So I don't

know. David Mamet once said, `I don't know if that answers your question, but

it's a damn good answer to something.'

GROSS: That's a very good answer. You did well on the answer. I'm assuming

you're not going to tell us anything about how "The Wire" ends, even though

you shot it and you're probably in it, your character's probably in it, and

plus I want to be surprised, so even if you're going to tell me, I probably

wouldn't...(unintelligible)...

Mr. JOHNSON: See, the thing is, HBO gives us mind control drugs and I don't

even remember what happened now because they've erased it from our memories.

I'm going to have to watch it with you because I don't know.

GROSS: But I'm wondering what it was like to be--like, to shoot the final

part and know like, OK, now that the show is really over, you know, having

worked on the first and the last episode? And I'm also wondering if you went

back and watched the pilot before shooting the last one.

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah, I did. I went back and watched the pilot, for sure, and,

you know, a few other episodes as well. But it was bittersweet. You know, I

think "Homicide" went on two seasons too long. I mean, financially, I don't

think so but I think creatively it went on maybe two seasons too long. We

were desperately trying to stay on the air, and our powers-that-be were trying

to, you know, second-guess the audience's needs so--but "The Wire," I think,

to me, I would love the show to go on. I would love to spin off Gus Haynes

and have a newsroom show. I mean, I think there's a lot of life left in this

idea, but since it was decided that it was time to go, it ended really

strongly in my opinion. It ends, you know, it's a good way to wrap it up. So

it was bittersweet.

But it took forever to shoot because every time we would wrap a character, a

series wrap for a character, we'd stop and acknowledge their work, and they'd

speak, and then we'd all cry and then we'd start shooting again so it took

weeks to finish.

And then after that, I went out to California--this is a couple of months

later--and did the same thing on "The Shield," because "The Shield" was now

ending and I shot the very last...

GROSS: Oh no.

Mr. JOHNSON: ...one of "The Shield." So it was like, what am I, the series

killer now? And so...

GROSS: Not a serial killer but a series killer.

Mr. JOHNSON: And so--the series killer. So it was, again, bittersweet

because, you know, I really was fond of that show, too, and it was well

written. So when you look at the television landscape now and you see

what--how much crap is on there, and especially now with this writers' strike,

it's that much more poignant that we are losing two great shows like this, and

"The Wire" especially, that, you know, it still could have gone on, in my

opinion. I think there's way more cities in that--stories in that naked city.

GROSS: Clark Johnson will be back in the second half of the show. He

directed the pilot and the upcoming series finale of the HBO series "The

Wire." And this season he plays Gus Haynes, the city editor of The Baltimore

Sun. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with Clark Johnson. On this

fifth and final season of the HBO series "The Wire," he plays Gus Haynes, the

city editor of The Baltimore Sun. Johnson also directed the pilot and the

second episode of "The Wire" as well as the forthcoming series finale. He has

a similar place of honor on the FX cop series "The Shield," having directed

the pilot, the forthcoming series finale and some episodes in between. And

back in the '90s on yet another cop series, "Homicide," he played detective

Meldrick Lewis.

Here's a scene from "Homicide" in which Meldrick is interrogating a drug lord

named Luther Mahoney, who's been charged with conspiracy to commit murder.

Meldrick and another detective from narcotics are trying to get a confession

of murder from the drug dealer. The narcotics detective speaks first.

(Soundbite of "Homicide: Life on the Street")

Ms. TONI LEWIS: (As Detective Terri Stivers) You know, we did a raid on Bo

Jack Reed's stash.

Mr. ERIK DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) Ah, the late Mr. Reed. He had a

nice, long run before he fell. You find any of that poison?

Ms. LEWIS: (As Detective Terri Stivers) We did--not all of it, probably, but

enough to convince us that the bad bags were from his crew.

Mr. DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) Oh, I'll bet they were.

Mr. JOHNSON: (As Meldrick Lewis) Well, he was pointing the finger at you.

Mr. DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) Are you suggesting a motive?

Mr. JOHNSON: (As Meldrick Lewis) Well, we have, say, a theoretical drug

slinger, you know, he's marketing a viable product, proper purity, proper cut,

until some no-name, no-nothing old school, just-out-of-Jessup knucklehead

starts messing around with his home chemistry set and he starts killing off

the customers quick.

Ms. LEWIS: (As Detective Terri Stivers) As opposed to killing them slow.

Mr. JOHNSON: (As Meldrick Lewis) Even if this drug slinger, this theoretical

drug slinger, was a reasonable man, I mean, that guy might be compelled to

act.

Mr. DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) You know, your case makes sense. I like

it.

Mr. JOHNSON: (As Meldrick Lewis) I like it, too.

Mr. DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) Except I don't sling bags and I didn't kill

Bo Jack Reed.

Ms. LEWIS: (As Detective Terri Stivers) Then who did?

Mr. DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) A guy named Carlton Phipps.

Mr. JOHNSON: (As Meldrick Lewis) No, he's dead, too.

Mr. DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) You know, I heard that.

Mr. JOHNSON: (As Meldrick Lewis) Hm. See, our problem is that we don't have

any way of connecting Carlton Phipps with the murder of Bo Jack Reed. Well,

see, I worked that case.

Mr. DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) Mm-hmm.

Mr. JOHNSON: (As Meldrick Lewis) I talked to Carlton's people. You know

what they told me? They said he was despondent, that he may even have taken

his own life.

Mr. DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) He killed himself? He shot himself in the

back of the head? Who are you fooling? He was murdered. Bo Jack's people

came back on him. I mean, he had the gun that killed Bo Jack right on the

table in f...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. JOHNSON: (As Meldrick Lewis) Let me ask you this: How you know where

Carlton caught that bullet? And let me ask you this: How in the hell'd you

know what was on the table in front of the man?

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. DELLUMS: (As Luther Mahoney) Well, the word was all over about what

happened to Carlton.

Mr. JOHNSON: (As Meldrick Lewis) Oh, Luther, Luther, Luther, you just fell

for the oldest trick we got, baby.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's my guest, Clark Johnson, as Detective Meldrick Lewis on an

episode of "Homicide."

How'd you get the part on "Homicide"?

Mr. JOHNSON: You know, that's--I got to tell--but before I...

GROSS: Go ahead.

Mr. JOHNSON: Erik Dellums is--he's a great actor and he played Luther

Mahoney, and I've used him a few times. I call them "the Clark Johnson

players," and he's one of my actors that I--he played Bayard Rustin, a pivotal

character in my first film "Boycott," pivotal in the civil rights movement, a

completely different guy than that. It just--you know, from a saintly civil

rights activist to a ruthless drug lord is a great switch.

GROSS: Well, how'd you get the part in "Homicide"?

Mr. JOHNSON: The classic actor's story, you know? I was in California and I

really despised the town of Los Angeles in a lot of ways. It's just--I was

struggling there and I, you know, sleeping on a friend's couch. Two young

kids back East and trying to get going, and the one last audition before I go

home with my tail between my legs was this thing--this Barry Levinson, it was

the only name I knew at the time--audition for a new cop show. And I go to

read for the casting director, and there's no script. There's a book, and

it's a book by David Simon, "Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets," and

they said, `Pick anything from there and read from it.' So--what? So I read

from the actual book, and then of course the process continued and I went back

to New York and met Fontana and Barry, and, you know, subsequent auditions

later got the part, but that was the initial audition...

GROSS: But...

Mr. JOHNSON: ...and I read that and went `this is something that's going to

be groundbreaking, I just know it.'

GROSS: Was there a lot of dialogue in it that you had to read?

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah. I mean, his book, I mean, I don't know if you read it or

remember it but his book is like a screenplay in a lot of ways. There is a

lot of dialogue in it, so it wasn't hard to pick stuff out. And I think my

character is a combination of elements of that book that Paul Attanasio and

Simon--I mean, and Fontana and Barry Levinson concocted, but also elements of

my own experience of having played a cop on another series and my uncles back

home in Philadelphia with the porkpie hats. So it was a combination of things

that arrive at that character.

GROSS: Did they ever explain to you why they had you read from the book

instead of reading from a script?

Mr. JOHNSON: There was no script yet.

GROSS: Oh.

Mr. JOHNSON: As far as I know, there was no script yet. So, you know...

GROSS: So tell me about your uncles in Philadelphia who you just referred to.

Mr. JOHNSON: Oh, I idealized my uncles. I'm actually writing my parents'

life story right now, and they're a colorful bunch. And my Uncle Duke in

particular was the coolest cat I knew, and then my Uncle William was the

second coolest, and they both wore little porkpie hats but my Uncle William's

hat was always just a little too small.

GROSS: Which your character wore. Yeah, go ahead.

Mr. JOHNSON: Right. And my Uncle William's hat was always just a little too

small, which I thought that was hysterical. So I thought Mel's just got a

porkpie hat that's just a little too small. It used to fit.

GROSS: Right. Now, what did your uncles do?

Mr. JOHNSON: You know, regular round the way stuff from West Philadelphia.

My Uncle Duke was a, you know, late-night maintenance guy in a downtown office

building. And my Uncle William, God bless him, really didn't have a job since

he got out of the Army after the second world war, but he managed to get by.

He managed to get by. He always had something on the go. They were very much

influential in my young life.

I wanted to--and the scripts always supported this--I wanted to police the

streets of Baltimore from a position of being from the streets of Baltimore,

from, you know, knowing why a guy says what he says and why he had to say what

he says, not so much what made him think that but what made him have to say

what he said, and you only know that from knowing where he's coming from. I

mean, you know, you could say one thing to somebody when it's just me and you

in the room, Terry, but if my homey's right beside me, I might not be able to

respond to your question the way, you know, I honestly would if my homey

wasn't there. You know what I mean? So that dynamic as the cop that I'm

playing respects and understands that dynamic and the specifics of it so you

can't do that if you just drive around in a radio car.

I mean, that was the difference between--say, for instance, on "The Shield,"

with the LAPD it's a big, huge jurisdiction. You can't walk foot there. You

can't get to know your neighborhood. You don't have a neighborhood. It's

got, you know, 500 square miles is your neighborhood. So they're detached.

They're in their cars. They don't know there are Damon Runyon characters in

the neighborhood whereas in Baltimore, you arrested that guy eight times last

week, you know, he sat in the same coffee shop as you did this morning, so

it's a completely different way of looking at things.

GROSS: How familiar were you with the kind of streets that you patrolled in

"Homicide" and that you told stories about in "The Wire"?

Mr. JOHNSON: Well, I come from West Philadelphia and, you know, it's a rough

and tumble neighborhood. And that I drew from, but, you know, I don't do

drugs and I don't sling drugs and so I, you know, obviously I don't have a

specific reference about that, but we did get in there and get talking to

people and get hanging out, and then I rode around with the cops like every

cliched actor does. And in fact, the second day that we were in Baltimore,

Kyle and I were riding with some--with a uniform, one patrol car and they had

a call that they were responding to. It seemed like a minor domestic thing,

and went up into the high-rises, and over their radio and a couple of minutes

later we heard `shots fired, shots fired' and that turned out to be a cop was

shot.

And it became part of the storyline for us. Lee Tergesen played the cop that

was shot, and in this case killed, but our character survived and was blinded.

So this is me driving with some cops and watching him deal with the reality of

their world. It sort of humbles you that, you know, we're a bunch of

spoon-fed actors, but we have to play these guys for real, and that involves

seeing what their world is like. And it's pretty important for us to get out

there and feel it with them, but no more so than is supported by the writing.

GROSS: My guest is Clark Johnson. He played Detective Meldrick Lewis on

"Homicide." Now he co-stars on "The Wire" as the city editor of The Baltimore

Sun, Gus Haynes. He also directed the first two episodes of "The Wire" as

well as the upcoming series finale. We'll talk more after a break. This is

FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Clark Johnson. In the current season of "The Wire," he

plays the city editor at The Baltimore Sun, Gus Haynes. He also directed the

first two episodes of "The Wire" and directed the season finale, which is

coming up in a few weeks. he directed the pilot of "The Shield" and several

other episodes, as well, and played Detective Meldrick Lewis in the series

"Homicide."

Your parents are from very different backgrounds. Your father is

African-American. Your grandmother on his side cleaned houses for a living.

Mr. JOHNSON: Uh-huh.

GROSS: Your mother is white. She grew up, I read, on like Fifth Avenue or

something in New York.

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah. Partially, yeah.

GROSS: So did you feel like you had a foot in two really different worlds

when you were growing up?

Mr. JOHNSON: No, because--and that's part of what my script is that I'm

writing about my parents--is that my mother was disinherited. Her maiden name

is Clark. She comes from, you know, quite a successful family. You know,

parents split up and they both remarried, and her mother remarried quite

successfully in the financial sense, and so my mother on that side went to

Spence and, you know, had a doorman building on Park and 72nd in Manhattan.

But when she married my father, that was taken from her. Her father said that

she died in Europe and never spoke to her again. So she became--my

grandmother...

GROSS: Was she disinherited because your father is African-American or for

other reasons?

Mr. JOHNSON: Right. Right. Right. Because they, you know, they shamed the

family. I mean, that's the tragedy of that. Deeply disappointed her father,

and that completely surprised my mother because he had been one of the

military lawyers in the Nuremberg trials and large involvement in the

desegregation of the Army in the Truman administration, you know, so he was a

liberal for his time, but it's that classic "not next door and not my

daughter," you know? So it took her by surprise. So, to answer your

question, I never really had that side of the family until years later. So

there wasn't--and both my parents got involved in the civil rights movement

fairly early in my young life, so she became one of us as opposed to me

straddling the fence of two worlds.

GROSS: So when you were growing up, did you identify as African-American or

bi-racial?

Mr. JOHNSON: Absolutely. Always. And that was totally encouraged by both

parents. And, you know, the idea of walking down the street and only being

affected by half, in terms of racism, you know, it really doesn't make much

sense, you know? I didn't have--I come from people that had to sit in the

very back of the bus, not either/or, you know, so my blackness was never an

issue.

GROSS: Well, what about as an actor? Has race been an issue as an actor, and

have you played people of different racial backgrounds in movies and TV shows?

Mr. JOHNSON: Not really. I mean, you know, early in a young actor's career,

unless they're very lucky, you tend to--you know, you start getting the roles

of cop number one or dead guy on the street. And it says African-American and

a lot of times they'd look at me and go, `Oh, he's too light-skinned' or they

wouldn't say it outright but I'd know that they want somebody more ebonically

speaking or more whatever that fits their stereotype of what it means to be an

African-American. So early in your career you deal with those prejudices and

preconceptions. But then as you go along, obviously race was a factor in me

playing Gus Haynes on "The Wire," for instance, but it wasn't something that

they went, `oh well, he's not black enough to play this role.' So they start

to forget that sort of thing when you have a track record as an actor. You

start to get roles because you can play the role as opposed to what you look

like at that moment.

GROSS: Did you say race was a factor in "The Wire"?

Mr. JOHNSON: Well, to a certain extent. I mean, I'm sure they--you know, it

was interesting to them to have an African-American in the newsroom. The

Baltimore Sun, sadly, is pretty much lily white, and I think it was Simon--a

little jab at the Sun, saying, you know, diversify. It's a city that's 60 or

80 percent black and yet this isn't reflected at all. So that had something.

But there was like two speaking characters in that whole newsroom that were

black so it didn't really go too far. But so I'm sure that had something to

do with it. Not in a sinister way, but you know, just reflecting what it is,

is all.

GROSS: Now, your parents--I think your father is or was a professor?

Mr. JOHNSON: He was, yeah.

GROSS: Of?

Mr. JOHNSON: Kinesiology. He taught phys ed and kinesiology.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. And your mother set up development or relief programs in...

Mr. JOHNSON: Right.

GROSS: ...developing countries?

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah. She worked for relief organizations like Save the

Children and, you know, sending university students overseas and, you know,

very, very energetic and enlightened, you know, global citizen. She spent a

lot of time in Africa and in the third world in general, setting programs up,

setting up teachers or engineers or whatever is needed in a particular area.

So as a kid, instead of going to summer camp, we would be in Bogata, Columbia,

or Haiti, or someplace where there was a real need for American help. And

that's what she did. So we're proud.

GROSS: That must give you an interesting perspective on race and ethnic

identity when you're a kid, to travel like that.

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah, for sure. I mean, my upbringing is interesting because,

leaving West Philadelphia as a kid and growing up partially in Toronto, it's a

different perspective on what--I didn't learn the word "ghetto" until I came

to Toronto. I never heard that word in Philadelphia, so a different

perspective on, `oh, that's what you--oh, that's how you see'...

GROSS: How did you know that acting was right for you?

Mr. JOHNSON: My mom took me to an audition--because we were all in church

choir and always sang in the kitchen and goofed around, and my mother thought

it would be fun to take me to an audition. Me and my actually younger sister

Molly to an audition for a production of "South Pacific" in New York, and we

got it. And so they would--when there was an East Coast show starting up--and

this is in the '60s, you know, the big touring musicals, they'd say, `Get

those Johnson kids,' so the four of us would be in these great shows like

"Porgy and Bess" and "Finian's Rainbow" and "South Pacific" so I got the bug

early, but didn't really--again, you know, I went to one audition. I wasn't,

you know, a stage brat. I just did one audition and I grew up in the wings.

GROSS: So what's one of the best songs you got to sing?

Mr. JOHNSON: Oh. Mm. God. The very first song I sang was in French, and I

didn't even know that there was a French language. I was nine, and I sang

"Dites-Moi" in "South Pacific" and that was--that was fun. I'll sing it for

you right now.

GROSS: Please.

Mr. JOHNSON: No. I'm not.

GROSS: Oh, come on.

Mr. JOHNSON: I got a cold. I was nine.

GROSS: Aw, it's always something. No, you grew up partially in Canada and

live partially there now...

Mr. JOHNSON: Right.

GROSS: ...and you did some of your early film work with the great Canadian

director David Cronenberg...

Mr. JOHNSON: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...and I think you worked on "The Dead Zone," "Videodrome" and "The

Fly"?

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah, I did special effects.

GROSS: Tell me something great you learned doing special effects for David

Cronenberg.

Mr. JOHNSON: That he loves blood.

GROSS: Yes, he does. We talked about that. And he's so like into the

different kinds of blood.

Mr. JOHNSON: I know. I know. He's such a--I mean, he's really--I mean, I

was like the fifth special effects hand on all his movies. I barely had the

courage to say hello to him when I worked on his crews. But I got the sense

that he's just a really nice guy, a really normal guy--you know, crazy

thoughts but a normal guy. And to see the movies, you go, wow, that's the

same guy? And I'm sure that's true of other directors, but I thought that was

interesting. You know, I cut myself on "The Dead Zone," I fell off a truck

and opened up my arm, took about 38 stitches and a pint or two of blood, and

he came with little pail and said, `Let's keep the blood.'

GROSS: Oh no. Really?

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah. He was joking around, but...

GROSS: Did he use it in the film?

Mr. JOHNSON: That was really--no!

GROSS: Oh, OK.

Mr. JOHNSON: I was doing effects. I was blowing stuff up. I was--we

were--we were making--we were doing a scene were we had Chris Walken--this is

going back a ways. Chris Walken is in a burning room, and it was a big, huge

scene. And he took the time to come and see if I was OK.

GROSS: So, did you hurt yourself while Christopher Walken was getting blown

up?

Mr. JOHNSON: Yeah. Yeah. That's part of it, you know.

GROSS: Did you get a good shot out of it?

Mr. JOHNSON: Well, I guess they did. I'm just, you know--I limped off. I

mean, what am I going to do? I'm just the...

GROSS: What were you doing? What were you doing in that shot?

Mr. JOHNSON: I was--I was the effects guy. I was off camera. You know, I

forget what specifically--I think I might have been tripping a bomb, you know,

knocking something or lighting a fire bar--I can't remember. But it was a big

scene where the whole room catches on fire.

GROSS: OK.

Mr. JOHNSON: The good old days. I still love effects. I kept doing special

effects up until right--halfway through "Homicide" I would still take calls to

go, you know, flip a car or something. I got a kick out of it. Still do.

GROSS: Well, Clark Johnson, it's been great to talk with you. Thank you so

much.

Mr. JOHNSON: Fun to talk to you, too, Terry. Thanks for having me on.

GROSS: Clark Johnson directed the pilot and the upcoming series finale of the

HBO series "The Wire," and this season he plays Gus Haynes, the city editor of

The Baltimore Sun.

Tomorrow we'll hear from the actor who plays Omar on "The Wire," Michael

Kenneth Williams.

Coming up, jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews two albums featuring pianist

and singer Andy Bey. This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Kevin Whitehead on newly-issued live album from Andy Bey

TERRY GROSS, host:

Andy Bey was a child piano prodigy and teenage pop singer before he began

touring in the vocal trio Andy Bey and the Bey Sisters. Later, in the 1970s,

he recorded with Horace Silver, Stanley Clarke and others. But Bey's career

really took off when he was rediscovered in the '90s. Jazz critic Kevin

Whitehead reviews a newly issued Andy Bey live album that isn't exactly new.

(Soundbite of "It Ain't Necessarily So")

Mr. ANDY BEY: (Singing) Jonah, he lived in a whale

Ohhhh

Jonah, he lived in a wave

For he made his home in that fish's abdomen

Oh, Jonah, Jonah, Jonah, Jonah

He lived in a whale...

(End of soundbite)

Mr. KEVIN WHITEHEAD: Andy Bey on piano and vocals, bringing out the gospel

in "It Ain't Necessarily So" from "Porgy and Bess." It's on Bey's album "Ain't

Necessarily So," a belatedly issued live date from 1997, early in his ongoing

revival.

Bey has extraordinary range as a singer. He can play the romantic baritone

like Billy Eckstine, but he'll also swoop over and under a baritone's normal

range from a strong falsetto to a sub-basement. And he may fade from a holler

to a whisper as he does it. He doesn't mind showing off what he can do, but

doesn't lapse into mere showboating.

(Soundbite of "It Ain't Necessarily So")

Mr. BEY: (Singing) I'm preaching, preaching

Preaching preaching my sermon so

I heard it ain't, that it ain't, that it ain't

Necessarily so

Preaching...

(End of soundbite)

Mr. WHITEHEAD: Andy Bey has a great feeling for Duke Ellington's music. He

can jab the piano like Ellington and has recorded a few of his tunes. Duke's

"I Let a Song Go out of My Heart" gets knockout treatment here. Ellington

loved eccentric soloists but didn't always hire the best singers, so it's

tempting to imagine what he might have done with this virtuoso.

(Soundbite of "I Let a Song Go out of My Heart")

Mr. BEY: (Singing) I let a song go out of my heart

It was the sweetest melody

I know I lost heaven

Because you were the song

Since you and I, I, I have drifted apart

Life really doesn't mean a thing to me

Please, please come back, sweet music

I know I was wrong

(End of soundbite)

Mr. WHITEHEAD: Andy Bey's made some very good records since his comeback,

but this superior one gets an extra boost from the base and drum team of Peter

Washington and--no relation--Kenny Washington. They lock in with Bey the

pianist and make him more of a rhythm singer, as on this upbeat version of

depression-era tearjerker "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?"

(Soundbite of "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?")

Mr. BEY: (Singing) Once in khaki suits, gee we looked swell

Half a million men went slogging through hell

I was the kid with the drum

Say, don't you remember my name

Is Al

It was Al all the time

Say, don't you remember

I'm your pal

Brother, can you spare a dime?

(End of soundbite)

Mr. WHITEHEAD: Bey's taste for pushing the limits goes back to the family

act he had with elder siblings Salome and Geraldine 45 years ago.

Bey fans may have missed, but shouldn't have, a recent reissue of 1966's

"'Round Midnight" by Andy and the Bey Sisters. There's more Ellington, more

risk-taking and plenty of evidence Andy was already special way back

when--even if he had to wait another 30 years for the payout.

(Soundbite of "'Round Midnight")

Mr. BEY: (Singing) Memories always start

'Round midnight

Haven't got the heart

To stand those memories

When my heart is still with you...

And midnight knows it too

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Kevin Whitehead teaches English and American Studies at the University

of Kansas and he's a jazz columnist for emusic.com.

You can download podcasts of our show on our Web site, freshair.npr.org.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.