Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on November 4, 1997

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: NOVEMBER 04, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 110401np.217

Type: FEATURE

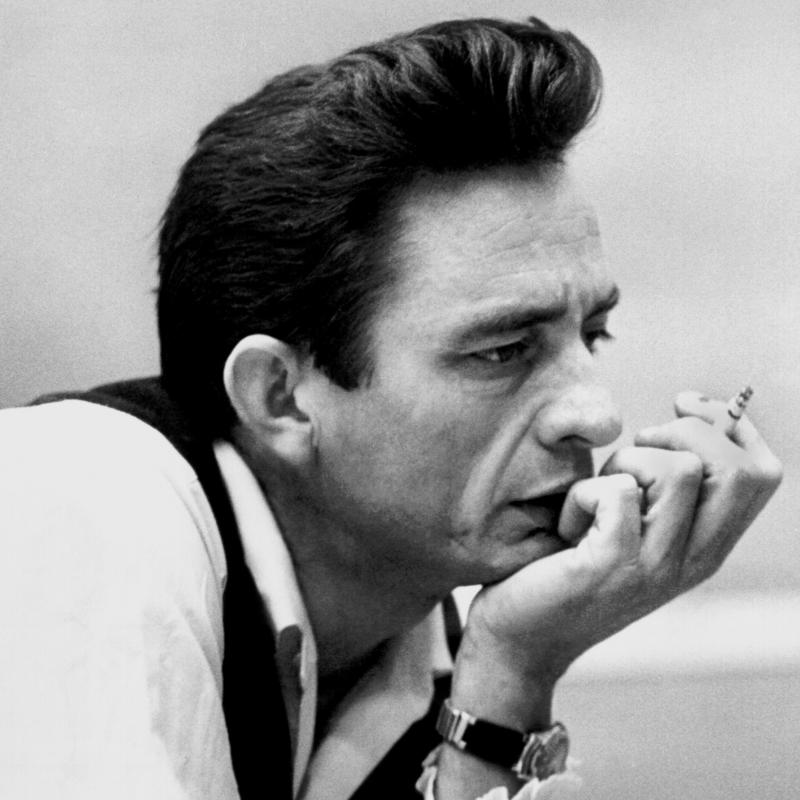

Head: Johnny Cash

Sect: Entertainment; Domestic

Time: 12:05

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is Fresh Air. I'm Terry Gross.

Last week, Johnny Cash announced that he has Parkinson's Disease, which interferes with movement, causing rigidity and tremors. He canceled the book tour that he had just begun. Today, we'll hear the interview we recorded shortly before he ended the tour.

At the age of 65, Johnny Cash is already a survivor of drug addiction and heart disease. Johnny Cash is in the Country Music Hall of Fame and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

As Cash says in his new autobiography, after his hits in the '60s, he didn't sell huge numbers of records but he kept making music he's proud of. But in 1994, he hooked up with record producer Rick Rubin, who had produced many rap and rock hits. And as the autobiography says, the Cash and Rubin collaborations transformed Cash's image from Nashville has-been to hip icon. And it gained him a new, young audience. Let's begin with a song from the latest Cash CD called "Unchained." This is called "Spiritual."

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP OF "SPIRITUAL")

JOHNNY CASH, SINGER:

Jesus, I don't want to die alone,

Jesus, oh, Jesus. I don't want to die alone.

My love wasn't true,

Now all I have is you.

Jesus, oh, Jesus, I don't want to die alone.

GROSS: That's "Spiritual" from Johnny Cash's latest album,

"Unchained." Johnny Cash, welcome to Fresh Air. A great pleasure to have you on the show.

CASH: Thank you. Thank you very much.

GROSS: The song we just heard isn't exactly a conventional hymn, but it is a hymn by a man who doesn't want to die alone and is feeling kind of...

CASH: Yeah.

GROSS: ... forsaken. You've always sung hymns of one sort or another during your career, of every sort, I suppose. Why have they always spoken to you so deeply?

CASH: Well, I don't know. It's the -- I didn't write the song. It was written by a young man named Josh somebody; I've forgotten. And it's as -- so it's named "Spiritual." But the thing is, I got this song under my skin when I first heard it. And the song is so honest, you know. The way he was, he was trying to get to God, and from a very low place, from the depths. And it just really moved me and I just felt like I just had to record it.

GROSS: Your career has in many ways been about both the sacred and the profane. You've always been Christian and have always sung hymns. And, on the other hand, there were times in your life when, as you write in your book, when you'd been in and out of jails, hospitals, car wrecks, when you were a walking vision of death. And that's exactly how you felt, you say in your book.

CASH: Mmm-hmm.

GROSS: Have you always been aware of that contradiction? You know, the sacred and the profane, running through your life?

CASH: Yeah. Kristofferson wrote a song, and in that song was a line that says -- he wrote the song about me -- "He's both a -- He's a walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction." And I've always explored various areas of society, and the lovely young people. And I had an empathy for prisoners and did concerts for them. Back when I thought that it would make a difference, you know, that they really were there to be rehabilitated.

GROSS: You grew up during the Depression. What are some of the things that your father did to make a living while you were a boy?

CASH: My father was a cotton farmer first. And -- but he didn't have any land, or what land he had he lost it in the Depression. So, he worked as a woodsman and cut pulp wood for the paper mills. Rode the rails on -- in boxcars, going from one harvest to another to try to make a little money picking fruit or vegetables. He did every kind of work imaginable, from painting to shoveling to herding cattle. And he's always been such an inspiration to me because of the varied kinds of things that he did and the kind of life he lived. He inspired me so, that all the things he did, so far from being a soldier in World War I to being an old man on his patio, sitting on the porch watching the dogs, you know. I think about his life and it would inspire me to go my own other direction. And I just like to explore minds and the desires of the people out there.

GROSS: You know, it's interesting that you say your father inspired you so much. I'm sure you wouldn't have wanted to lead his life, picking cotton.

CASH: I did. Until I was 18 years old, that is.

GROSS: Mmm-hmm.

CASH: Then I picked the guitar and I've been picking it since.

GROSS: Right. Did you have a plan to get out? Did you very much want to get out of the town where you were brought up and get out of picking cotton?

CASH: Yeah. I knew that when I left there at the age of 18 I wouldn't be back. And it was kind of common knowledge among all the people there that, when you graduate from high school here, you go to college or you go get a job or something, and do it on your own. And, having been familiar with hard work, it was no problem for me. But first, I hitchhiked to Pontiac, Michigan, and got a job working in the Fisher Body, making those 1951 Pontiacs. I worked there three weeks, got really sick of it, went back home and joined the Air Force.

GROSS: You have such a wonderful, deep voice. Did you start singing before your voice changed?

CASH: Ah, yeah. I've got no deep voice today; I've got a cold. But, when I was young, I had a high tenor voice. I used to sing Bill Monroe songs. And I'd sing Dennis Day songs like...

GROSS: Oh, no.

CASH: Yeah. Songs that he'd sing on the Jack Benny Show.

GROSS: Wow.

CASH: Every week he'd sing an old Irish folk song. And next day, in the fields, I'd be singing that song; if I was working in the fields. And I always loved those songs and, with my high tenor, I thought I was pretty good, you know. Almost as good as Dennis Day. But, when I was 17, 16, my father and I cut wood all day long and I was swinging that cross-cut saw and hauling wood; and when I walked in the back door late that afternoon, I was singing "Everybody gonna have religion and glory. Everybody gonna be singing a story." I'd sing those old Gospel songs for my mother, and she said, "Is that

you?" And I said, "Yes, ma'am." And she came over and put her arms around me and said, "God's got his hands on you." I still think of that, you know.

GROSS: She realized you had a gift.

CASH: That's what she said. Yes. She called it the gift.

GROSS: Well, how did you feel about your voice changing? It must have stunned you, if you were singing like Dennis O'Day and then suddenly you were singing like Johnny Cash.

CASH: Well, I don't know. I guess, when I was a tenor I just -- and when it changed, I thought, well, it goes right along with these hormones. And everything's working out really good, you know. I felt like my voice was becoming a man's voice.

GROSS: Right. Right. So, did you start singing different songs as your voice got deeper?

CASH: Mmm-hmm. "Lucky Old Sun." "Memories Are Made of This." "Sixteen Tons." I developed a pretty unusual style, I think. If I'm anything, I'm not a singer, but I'm a song stylist.

GROSS: What's the difference?

CASH: Well, I say I'm not a singer, so that means I can't sing. But-- doesn't it?

LAUGHTER

GROSS: Well, but, I mean, that's not true. I understand you're making a distinction, but you certainly can sing. Yeah. Go ahead.

CASH: Thank you. Well, a song stylist is, like, to take an old folk song like "Delia's Gone" and do a modern, white man's version of it. A lot of those I did that way, you know. I would take songs that I'd loved as a child and redo them in my mind for the new voice I had. The low voice.

GROSS: I know that you briefly took singing lessons, and you say in your new book that your singing teacher told you, you know, don't let anybody change your voice. Don't even bother with the singing lessons. How did you end up taking lessons in the first place?

CASH: My mother did that. And she was determined that I was going to leave the farm and do well in life. And she thought, with the gift I might be able to do that. So she took in washing. She got a washing machine in 1942, as soon as they got electricity, and she took in washing. She washed a school teacher's clothes and anybody she could. And sent me for singing lessons, for $3 per lesson. And that's how she made the money to send me.

GROSS: What was your reaction when the teacher told you, don't let anybody change what you're doing, don't, you know, I'm not going to teach you anymore?

CASH: I was pretty happy about that. I didn't really want to change, you know, I felt good about my voice.

GROSS: My guest is Johnny Cash. He has a new autobiography. More after a break. This is Fresh Air.

(BREAK)

GROSS: Back to our interview with Johnny Cash, recorded a couple of weeks ago.

You left home when you were about 18. And then, how old were you when you actually went to Memphis?

CASH: Well, I went to Memphis after I finished the Air Force in 1954. I lived on that farm until I went to the Air Force. I was in there four years. And when I came back, I got married and moved to Memphis. Got an apartment. Started trying to sell appliances at a place called Home Equipment Company. But I couldn't sell anything. And didn't really want to. All I wanted was the music. And if somebody in the house was playing music when I, when I would come, I would stop and sing with them. Like one time, Gus Cannon, the man who wrote "Walk Right In," which was a hit for the Rooftop Singers, and I sat on the front porch with him, day after day, when I found him, and sing those songs.

GROSS: When you got to Memphis, Elvis Presley had already recorded "That's All Right." Sam Phillips (ph) had produced him for his label Sun Records. You called Sam Phillips and asked for an audition. Did it take a lot of nerve to make that phone call?

CASH: No. It just took the right time. I was fully confident that I was going to see Sam Phillips and to record for him. When I called him, I thought, I'm going to get on Sun Records. So, I called him and he turned me down flat. Then two weeks later, I called. Turned down, turned down again. He told me over the phone that he couldn't sell gospel music. So -- because it was independent and not a lot of money, you know. So, I didn't press that issue. But, one day I just decided that I'm ready to go. So, I went down with my guitar and sat on the front steps of his recording studio and met him when he came in. And I said, I'm John Cash. I'm the one that's been calling. And if you'd listen to me, I believe you'll be glad you did. And he said, Come on in. That was a good lesson for me, you know, to believe in myself.

GROSS: What was the audition like?

CASH: It was about three hours of singing with just my guitar. Songs, a lot of them, like the songs that are in my first American Recordings album.

GROSS: So, what did Phillips actually respond to most of the songs that you played him?

CASH: He responded most to a song of mine called "Hey, Porter," which was on the first record. But he asked me to go write a love song, or maybe a bitter weeper. So, I wrote a song called "Cry, Cry, Cry," went back in and recorded that for the other side of the record.

GROSS: You say in your book that you had to do 35 takes of "Cry, Cry, Cry." Why did it take so many takes?

CASH: It was too simple. We were trying to make something complicated out of it and it was the simplest song in the world, ever written. And, invariably, at some time during a take the guitar player would mess up or the bass player or I would mess up and we'd have to do it over. It's not unusual, though, to do a song 35 times.

GROSS: Were you nervous because it was your first recording?

CASH: No. Not at all. I had confidence that I was going to do it. I'd been singing in Germany in the Air Force. I'd been singing with my little group called the Lansburgh (ph) Barbarians. And we played in honky-tonks and gasthauses (ph) and wherever we could, you know, when we weren't working.

GROSS: Well, why don't we hear "Cry, Cry, Cry," which was on the

first single that Sun Records released by you.

CASH: OK.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP OF "CRY, CRY, CRY")

CASH:

Everybody knows where you go when the sun goes down,

I think you only live to see the lights uptown,

I wasted my time when I would try, try, try,

'Cause when the lights have lost their glow, you'll cry, cry, cry.

Soon your sugar daddies will all be gone,

You'll wake up some cold day and find you're alone,

You'll call for me, but I'm gonna tell you, 'bye, 'bye, 'bye,

When I turn around and walk away, you'll cry, cry, cry.

You're gonna cry, cry, cry and you'll cry alone,

When everyone's forgotten and you're left on your own,

You're gonna cry, cry, cry.

GROSS: That's Johnny Cash. His first single. And Johnny Cash has a new autobiography which is called "Cash: The Autobiography."

So, this record was the beginning of your recording career. What was it like when you started to go on tour? You know, after coming from the cotton fields, it's true, I mean, you'd been in the Army and you'd been abroad, you know, with the Army, but what was it like for you in the early days? Of getting recognized? You know, traveling around the country?

CASH: Well, when I started playing concerts, I went out from Memphis to Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee. Played the little towns there. But I would go out myself in my car and set up the show, get the show booked in those theaters. And then, along about three months later, Elvis Presley asked me to sing with him at the Overton Park Shell in Memphis. And I sang "Cry, Cry, Cry" and "Hey, Porter." And from that time on, I was on my way. And I knew it. I felt it. And I loved it. So, Elvis asked me to go on tour with him and I did. I worked with Elvis four or five tours in the next year or so. And I was always intrigued by his charisma. I just -- you can't be in the building without Elvis -- with Elvis without looking at him, you know? And he inspired me so, that -- with his fire and energy -- that I guess that inspiration from him really helped me to go.

GROSS: It's funny, I think of your charisma and his charisma as being very different forms of charisma. Because, I mean, he would move around so much on stage, and I think of your charisma as being a very, kind of, still, stoic kind of charisma.

CASH: Mmm-hmm. Mmm-hmm. Well, I'm an old man to him. I'm four years older than he was.

LAUGHTER

So, I was 23 when I started recording and Elvis was 19. And I was married. He wasn't. So, we didn't have a lot in common, common family life. But we liked each other and appreciated each other. So, he asked me to tour with him.

GROSS: Did you want that kind of adulation that he was getting from girls who would come see him?

CASH: I don't remember if I wanted it, but I loved it. Yeah, I did.

LAUGHTER

But, I didn't -- I only got it to a very small degree compared to Elvis.

GROSS: Right. What were the temptations like for a young married man like yourself on the road, you know, slowly becoming a star?

CASH: Fame was pretty hard to handle, actually. The country boy in me tried to break loose and take me back to the country, but the music was stronger. The urge to go out and do the gift was a lot stronger. And, the temptations were women -- girls, which I loved -- and then amphetamines. Not very much later, running all night, you know, in our cars on tour, and the doctor's got these nice pills that give us energy and keep us awake. So, I started taking those and I liked them so much I got addicted to them. And then, I started taking downers or sleeping pills to come down and rest after two or three days. So it became a cycle. I was taking the pills for a while and then the pills started taking me.

GROSS: I want to play what I think was your first big hit, "I Walk

the Line."

CASH: Mmm-hmm. That was my third record.

GROSS: And, you wrote this song. Tell me the story of how you wrote it. What you were thinking about at the time.

CASH: In the Air Force I had an old Wilcox-Kay (ph) recorder, and used to hear guitar runs on that recorder, going: dhoun, dhoun, dhoun dhoun. Like the chords on "I Walk the Line." And I always wanted to write a love song using that theme, you know, that tune. And so, I started to write the song. And I was in Gladewater, Texas, one night, with Carl Perkins and I said, "I've got a good idea for a song." And I sang him the first verse that I had written. And I said, "It's called, 'Because You're Mine'." And he said, "'I Walk the Line''s a better title." So I changed it to "I Walk the Line."

GROSS: Now, were you thinking of your own life when you wrote this?

CASH: Mmm-hmm. Mmm-hmm. It was kind of a prodding to myself to play it straight, Johnny.

GROSS: And was this -- I think I read that this was supposed to be a ballad. I mean, it was supposed to be slow, when you first wrote it.

CASH: Mmm-hmm. That's the way I sang it, yeah, at first. But Sam wanted it up, you know, up tempo. And I put paper in the strings of my guitar to get that "oonch-ch, oonch-ch, oonch-ch" sound, and with a bass and a lead guitar, there it was. Bare and stark, that song was, when it was released. And I heard it on the radio and I really didn't like it. And I called Sam Phillips and asked him to please not send out any more records of that song.

GROSS: Why?

CASH: But he laughed at me. I just didn't like the way it sounded, to me. I didn't know I sounded that way. And I didn't like it. I don't

know. But he said, "Let's give it a chance." And it was just a few days until -- that's all it took to take off.

GROSS: That's funny. I mean, you'd heard your voice before, hadn't

you?

CASH: Mmm-hmm.

GROSS: But -- so it was something in your own singing, you weren't liking when you heard it?

CASH: Well, the music and my voice together. I just felt like it was really weird. And -- but I got used to it very quickly. I don't know that I didn't -- I didn't hate it, but I just didn't like it. I thought I could do better.

GROSS: Well, let's hear "I Walk the Line." This is a great record. It was great then and it still is. This is Johnny Cash.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP OF "I WALK THE LINE")

CASH:

I keep a close watch on this heart of mine,

I keep my eyes wide open all the time,

I keep the ends out for the tie that binds,

Because you're mine, I walk the line.

GROSS: We'll hear more of our interview with Johnny Cash in the second half of the show. Johnny Cash has a new autobiography called "Cash." I'm Terry Gross and this is Fresh Air.

CASH:

Yes, I'll admit that I'm a fool for you,

Because you're mine, I walk the line.

(BREAK)

GROSS: This is Fresh Air. I'm Terry Gross. Back with more of our interview with Johnny Cash. It was recorded a couple of weeks ago, just a few days before he announced that he has Parkinson's Disease and canceled the rest of his book tour and his concerts through the end of the year. He has a new autobiography.

A little later, we'll hear Johnny Cash talk about his recent records,

produced by Rick Rubin, records which won Cash a new, young audience. We're going to hear a track from the first of those collaborations. The song is "The Beast in Me." And before we hear it, we'll get the story behind the song from the man who wrote it, Nick Lowe (ph), who is also Cash's former son-in-law. In 1995, Nick Lowe told me why he wrote "The Beast in Me" for Johnny Cash.

NICK LOWE, SONGWRITER: It was a little task I set myself, I suppose. I suppose I thought about it originally in 1980, and I thought up this terrific title, "The Beast in Me," which I thought would be so right. That's a start, I thought, for Johnny Cash. And I wanted to get a few, sort of, crypto-religious term, you know, terms in there and things like that. You know. It was a kind of a cynical exercise, except I thought the title was really good.

GROSS: But what was cynical about this?

LOWE: Well, because, you know, it was a sort of paint-by-numbers kind of thing, I suppose I was thinking of. You know, I thought "This is a big man, torn down" you know, because of this terrible thing within him, you know. And, I thought this is right up John's street. And I thought up the song and the first verse came very, very quickly. And it's one of those songs, really, where I said it all in the first verse. I couldn't really think of what else to say. Nonetheless...

LAUGHTER

being the consummate professional that I am, I went ahead and I finished the song rather quickly, really. And John, being the lovely man and wonderful musician that he is, spotted this. And he could see that I'd rushed this thing. And he said to me, gently, "Look, you're on to a good thing here, but you haven't quite got it right. I think you should have another shot at this." Which I did. Periodically. I'd, sort of, mentally get the song out and dust it off. Generally, after I'd seen him in the intervening years. As I say, this was in 1980 when I first thought it up. And he always, you know, when, after I'd seen him, say "How's 'The Beast in Me' song going, Nick?" So I'd dust it off a bit and I wouldn't really get any further. And he'd always ask me how it was going. And then, the year before last, I had a, sort of, a revelation. I realized the song wasn't actually really about Johnny Cash at all, it was kind of about me -- and most people I know. And once I realized that, suddenly, you know, a kind of a light went on and I managed to finish the song quite easily. And it all seemed to fall into shape. And I can't understand what all the trouble I had with it was.

GROSS: So, as you realized that it was about the beast in you also, there was more to be said?

LOWE: It's more the beast in one.

LAUGHTER

GROSS: The beast in one. I like that.

Songwriter and singer Nick Lowe, recorded in 1995. Well, let's listento Johnny Cash's recording of "The Beast in Me."

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP OF "THE BEAST IN ME")

CASH:

The beast in me is caged by frail and fragile bars,

Restless by day, and by night rants and rages at the stars.

God help the beast in me.

The beast in me has had to learn to live with pain,

And how to shelter from the rain,

And in the twinkling of an eye,

Might have to be restrained.

God help the beast in me.

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with Johnny Cash, recorded a

couple of weeks ago.

I think it was in the late 1950s that you started doing prison concerts, which you eventually became very famous for. What got you started performing in prison?

CASH: Well, I had a song called "Folsom Prison Blues" that was a hit just before "I Walk the Line," and people in Texas heard about it at the state prison and got to writing me letters asking me to come down there. So, I responded, and then the warden called me and asked if I would come down and do a show for the prisoners in Texas. And so, we went down, and there's a rodeo at all these shows that the prisoners have there. And in between the rodeo things, they asked me to set up and do two or three songs. So, that was what I did. I did "Folsom Prison Blues," which they thought was their song, you know, and "I Walk the Line," "Hey, Porter," "Cry, Cry, Cry." And then the word got around on the grapevine that Johnny Cash was all right and that you ought to see him. So the requests started coming in from other prisoners all over the United States. And then the word got around. So, I always wanted to record that, you know, to record a show, because of the reaction I got. It was far and above anything I had ever had in my life. The complete explosion of noise and reaction that they gave me with every song. So, then, I came back the next year and played the prison again. A New Year's Day show. Came back again a third year and did the show. And then I kept talking to my producers at Columbia about recording one of those shows. It's so exciting, I said, that the people out there ought

to share that, you know, and feel that excitement, too. So, a preacher friend of mine named, Floyd Gressett (ph) set it up for us. And Lew Robin (ph) and a lot of other people involved at Folsom Prison. So we went into Folsom on February 11, 1968 and recorded a show live.

GROSS: Before we hear one of the tracks from that live album, tell me what it was -- what kind of reaction surprised you the most when you were performing for prisoners.

CASH: Well, what really surprised me was, any kind of prison song I could do no wrong, you know. Whatever the prisoner song or San Quentin song of mine. But they felt like they could identify with me, I suppose, where I came from. I sang songs like "Dark as a Dungeon" or "Bottom of a Mountain," songs about the working man and the hard life. And, of course, they'd been through the hard life, all of them, or they wouldn't be there. So, they kind of related to all that, I guess, with the songs I chose. Very little of love songs. Very few. Mostly, you know, songs about the down-and-outer. And so, then, requests started coming in for me to go to other prisons. And they got overwhelming. So, I decided I would do two or three and I wouldn't do any more. Because, one thing, my wife was scared to death and the other women on the show were, too. So, I decided not to. It was still a great experience to get on stage and perform for those people.

GROSS: Well, why don't we hear "Folsom Prison Blues" from your "Live at Folsom Prison" record. This is Johnny Cash.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP OF "FOLSOM PRISON BLUES")

CASH: Hello. I'm Johnny Cash.

SOUNDBITE OF APPLAUSE AND CHEERING

I hear the train a-coming,

It's rolling 'round the bend,

And I ain't seen the sunshine since I don't know when.

I'm stuck in Folsom Prison.

And time keeps draggin' on.

But that train keeps a-rollin',

On down to San Antone.

When I was just a baby,

My mama told me, "Son,

Always be a good boy. Don't ever play with guns."

But I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die.

When I hear that whistle blowin',

I hang my head and cry.

GROSS: That's Johnny Cash "Live at Folsom Prison." And Johnny Cash has a new autobiography that's just been published.

: I guess Merle Haggard was in the audience for one of your San Quentin concerts.

CASH: Mmm-hmm.

GROSS: It must have been pretty exciting to find that out. That was before he...

CASH: Yes.

GROSS: ... recorded, I think, that he was in there.

CASH: Yeah, '68 and '69, right on the front row was Merle Haggard.

GROSS: Yeah. And, who knew?

CASH: I didn't know that until about 1963, '62. He told me all about it. And so, every show that I did there -- of course, the rest is history. For Merle. He came out and immediately had success himself.

GROSS: You know, it's interesting. You've always, or almost always,

worn black during your career. And I was interested in reading that your mother hated it, too.

LAUGHTER

CASH: She -- yeah. Yes, she did.

GROSS: So we have something in common. Mothers don't like black.

CASH: Mmm-hmm, Yeah. But I love it.

GROSS: Me, too.

LAUGHTER

But you gave in for a while. She started making you bright, flashy outfits. Even a nice white suit.

CASH: Yeah, mmm-hmm.

GROSS: What did it feel like for you to be on stage in bright colors? Or all in white?

CASH: Well, that was 1956, and I hadn't been wearing the black for

very long. It was OK. I would wear anything my mother made me, you know. I just couldn't afford to turn her down. But before long I decided to start with the black and stick with it because it felt good to me on stage. That figure there in black and everything coming out his face. That's the way I wanted to do it.

GROSS: My guest is Johnny Cash. He has a new autobiography. More

after a break. This is Fresh Air.

(BREAK)

GROSS: Back to our interview with Johnny Cash.

You married your second wife -- your wife, June Carter, now June Carter Cash, in 1968. How did you first meet the members of the Carter family, the, kind of, first family of country music?

CASH: I met June at the backstage at the Grand Ol' Opry, when I did my first appearance as a guest artist. And that was five years again -- five years more 'til I saw her again. And we started working together, touring beginning in Des Moines on -- in January 1962. And we've been together ever since. I met her family on about my second tour that we had June on, because I asked them to all come and be a part of the show. So, I kind of got into those people and became one of their family. And it felt good to go out with them.

GROSS: What was it like, traveling with a family instead of being on your own? Being on your own, leaving the family behind?

CASH: I really don't like to do an appearance without June Carter. And what it would be like, being alone? It would be awfully lonely to me. I'm very comfortable with, you know, how we do it, with my wife and my son on the show, and a daughter or two. And it feels so good. I would hate to think that I had to do it all alone.

GROSS: Did it change your life to have a family that really understood the performing life because it was their life, too?

CASH: Very much so. Yeah. Right.

GROSS: What was the difference? I mean, why was that so important?

CASH: Well, there's something about families singing together that is just better than any other groups you can pick up or make, you know. If it's family, if it's blood-on-blood, then it's gonna be, it's gonna be better. The voices, singing their parts, are going to be tighter and they're going to be more on pitch. Because it's, as I said, it's blood line on blood line. And, it's always really comfortable and easy for me to sing a tune, or any of those girls.

GROSS: A few years ago, you started making records with Rick Rubin. Tell me how you and he first met up. It seemed, initially, like a very improbable match. He had produced a lot of rap records and produced the Beastie Boys, and the Red-Hot Chili Peppers. You know, it would seem like a surprising match. It ended up being a fantastic match. How did he approach you?

CASH: Well, my contract with Mercury-Polygram (ph) Nashville was about to expire and I never had really been happy. The company, the record company just didn't put any promotion behind me. I think one album, maybe the last one I did, they pressed 500 copies. And I was just disgusted with them. So I decided I'd just do my thing. I'll do my tours and writing and that's all I need. So, that's what I was trying to do, but I got hungry to be back in the studio, to be creative and put something down, you know, for the fans to hear. And about that time that I got to feeling that way, Lew Robin, my

manager, came to me and talked to me about a man called Rick Rubin that he had been talking to, that wanted me to sign with his record company. It was American Recordings. I said I liked the name. Maybe it'd be OK. So, I said I'd like to meet the guy. I'd like for him to tell me what he can do with me that they're not doing now.

So, he came to my concert in Orange County, California -- I believe this was, like, '83, when he first came -- and listened to the show. And then, afterwards, I went in the dressing room and sat and talked to him. And, you know, he had -- his hair, I don't think it's ever been cut --and very -- dresses like a hobo -- usually. Clean. But was the kind of guy I felt comfortable with, actually. I think I was more comfortable with him than I would have been with a producer with a suit on.

"Well," I said, "what are you going to do with me that nobody else hasbeen able to do to sell records with me?" And he said, "Well, I don't know that we will sell records." He said, "I would like you to go with me and sit in my living room with a guitar and two microphones and just sing to your heart's content, everything you ever wanted to record." I said, "That sounds good to me." So, I did that. And day after day, three weeks, I sang for him. And when I finally stopped -- he had been saying, like the last day or so, he'd been saying, "Now, I think we should put this one in the album." So, without him saying, "I want to record you and release an album," he started saying, "Let's put this one in the album."

So, the album, this big question, you know, began to take form, take shape. And Rick and I would weed out the songs. There were songs that didn't feel good to us that we would say, "Let's don't consider that one." And then we'd focus on the ones that we did like, that felt right and sounded right. And if I didn't like the performance on that song, I would keep trying it and do take after take until it felt comfortable with me and felt that it was coming out of me and my guitar and my voice as one. That it was right from my soul. That's how I felt about all those things in that first album. And I got really excited about it. But then we went into the studio and tried to

record some with different musicians and it didn't -- didn't sound good. It didn't work. So, we put together the album with just a guitar and myself.

GROSS: I was really glad you did it that way. There's something just so naked about it. Something so just emotionally naked.

CASH: (Unintelligible)

GROSS: And there's so much emotion in your voice. And it just all, you know, comes across really clearly.

CASH: Thank you.

GROSS: I think these records and the touring that you've done with them has helped introduce you to a younger audience that wasn't around during your earlier hits and maybe knew your reputation but didn't really know your music very well. And I'm wondering what that experience has been like for you, to play to younger audiences who are first getting acquainted with your music?

CASH: It feels like 1955 all over again.

LAUGHTER

It really does. It really does. And the ones who've been into my new recordings are becoming familiar with some of the old stuff like "Folsom" and "I Walk the Line" and "Ring of Fire." And those songs now just really get a reaction like I did on my songs back in the '50s. But it sounds -- it feels so good, with those young people. And the adulation, I just love it. I've always been a big ham. I just eat it up. Naw, I'm very appreciative to them.

GROSS: I want to play something from your first collaboration with Rick Rubin, which came out, I guess, a couple of years ago. And this is your reworking of the old song "Delia." "Delia's Gone." And, you made this the story of a murderer. And it's a very chilling song the way -- with the lyric that you've written and the way that you sing it. Tell me why you wanted to rewrite the song and how you first knew the song.

CASH: Well, there were bits in the lyrics of the old song of a good story. I mean, he thinks about the woman. He kills the woman. And buries her. And then he hears her footprints in the night around his cell. But the song is an old levee camp holler that was sung by the people who were building the levees back in the 'teens and then the '20s. And I always loved the song, but when I recorded it the first time in the early '60s, I changed some of the lyrics and added some. And then, when I recorded the song this time, I wrote a couple of new verses and changed some of the other words. So, the song, it seems to me, is still a part of me, in my soul, on my mind. And that's why I worked it over and added something to it.

GROSS: Why don't we hear "Delia's Gone" from Johnny Cash's "American Recordings" CD. And Johnny Cash, I want to thank you so much for talking with us.

CASH: I want to say, you're really good at what you do. And I appreciate you. Thank you.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP OF "DELIA'S GONE")

CASH:

Delia, oh, Delia,

Delia, all my life,

If I hadn't a shot poor Delia,

I'da had her for my wife.

Delia's gone,

One more round,

Delia's gone.

I went up to Memphis,

And I met Delia there,

Found her in her parlor,

And I tied her to her chair.

Delia's gone,

One more round,

Delia's gone.

She was low-down and triflin',

And she was cold and mean,

Kind of evil,

Make me want to grab my submachine.

Delia's gone,

One more round,

Delia's gone.

First time I shot her,

I shot her in the side,

Hard to watch her suffer,

But with the second shot she died.

Delia's gone,

One more round,

Delia's gone.

But, jailer, oh, jailer,

Jailer, I can't sleep,

'Cause all around my bedside,

I hear the patter of Delia's feet.

Delia's gone,

One more round,

Delia's gone.

So, if your woman's devilish,

You can let her run,

Or you can bring her down,

And do her like Delia got done.

Delia's gone,

One more round,

Delia's gone.

Delia's gone,

One more round,

Delia's gone.

GROSS: "Delia's Gone" from Johnny Cash's CD, "American Recordings." His new autobiography is called "Cash." Our interview was recorded a couple of weeks ago, just a few days before he announced that he has Parkinson's Disease.

This is Fresh Air.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Johnny Cash

High: Host Terry Gross talks with singer Johnny Cash about his career. He has written a new autobiography called "Cash." The interview was recorded a few days before Cash announced that he has Parkinson's Disease.

Spec: Music; Johnny Cash; Recording Industry; Arts

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1997 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1997 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: NOVEMBER 04, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 110402NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Internet

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:50

TERRY GROSS, HOST: The ever-accelerating pace of technological change. That's one of those phrases you run into all the time in the press. But our linguist Geoff Nunberg notices that we're capable of becoming disillusioned with each new wonder technology provides.

GEOFF NUNBERG, LINGUIST: Just a few years ago, the Internet was going to be an unmixed blessing. We were going to tear down the walls of all the libraries and just let all that information float free in space, where anybody could have access to it.

As one visionary put it: "Cyberspace. A world in which the global traffic of knowledge, secrets, measurements, indicators, entertainments takes on form, sights, sounds, presences, never seen on the surface of the Earth, blossoming in a vast electronic night."

That was written back in 1991, and you can sort of tell. The problem isn't that the writer got the Internet wrong. The "global traffic of knowledge, secrets, measurements, entertainments," that's the World Wide Web to a tee.

But the unbridled enthusiasm for the new realm has waned decidedly as people have started to spend a bit of time in it. That "vast electronic night" isn't quite so romantic when you're stumbling around, trying to find your slippers amongst all the other junk on the floor.

It's true that a lot of this comes with the territory. All the misinformation, the vanity pages, the porn, the infomercials. Well, what did we expect? When you tear down the walls of the library, you shouldn't be surprised to find all the street people camped out in the reading room.

And users are only just beginning to learn what library cataloguers have known for a long time: just how hard it is to find your way around when you have only words to do your bidding.

You can get a pretty graphic sense of the confusion when you log on to a web site called Voyeur, which is provided by the people who run the Magellan Internet Search Service.

Every 15 seconds or so, the Voyeur site throws up a dozen randomly selected strings of search words that people have typed into the search engine. They roll out in a jumble.

"Cherubim." "Fixed income derivatives." "Up skirt. White panties." "Do skunks turn white in the winter?" "Crack." "Eisenhower High School 1981." "Pamela Anderson's feet." "What would Jesus have done?"

What a bunch. It's like overhearing the babble of voices around a subway newsstand as you rush to catch your train. Except that few of these queries are designed to get the right pages off the rack.

I don't know what was in the mind of the person who typed in the word, "crack," for example, which pulled down an assortment that included porn sites, drug information, the descramblers that hackers call "cracks," and a technical report on stress in metals. I'm pretty sure, though, that the requester was shortly complaining about what a mess the Internet is.

The only people who seem exempt from this problem are the porn seekers. Their search strings are as inept as any others: dogs getting it, shaven sluts, school girls, or the plaintive, one-word query, "nookie."

But it turns out that most of these lame efforts hit their mark quite well. This, thanks to the accommodating porn providers who know how the search engines work and laid their sites with just about every word and expression that someone might enter i the hope of reaching them. There was one I saw that listed five different spellings for fellatio.

In fact, the porn consumers must be about the only users of the web who don't have to disabuse themselves of the impression that the search engines can read their minds. But then, theirs are pretty easy minds to read.

But what about the rest of us, whose objectives may be a little more difficult to grasp? The visionaries keep telling us that help is just around the corner in the form of intelligent agents. Systems that will figure out our interests and taste and take us unerringly to just the information we're looking for.

But it's clear that the people who glibly describe these systems haven't ever watched a flesh-and-blood librarian struggling to extract a sense, from the incoherent mumbles of the customers who present themselves at the reference desk.

It's true, there will be tools to make navigating the net a lot easier. But in the end, users are going to have to spend a lot of time learning to meet the technology halfway, the way we spend a couple of years of junior high school learning to find things in the dictionary.

Or, maybe it's just a matter of doing the old lessons right. That's one thing the visionaries didn't mention about cyberspace: spelling counts.

GROSS: Geoff Nunberg is a linguist at Stanford University and the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center.

Dateline: Geoff Nunberg; Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Linguist Geoff Nunberg ponders just how hard it is to find your way around the Internet when you have only words to do your bidding.

Spec: Internet; World Wide Web; Technology; Language; Computers

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1997 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1997 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior writtenpermission.

End-Story: Internet

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.