Francis Ford Coppola On Film, Wine, and Literature.

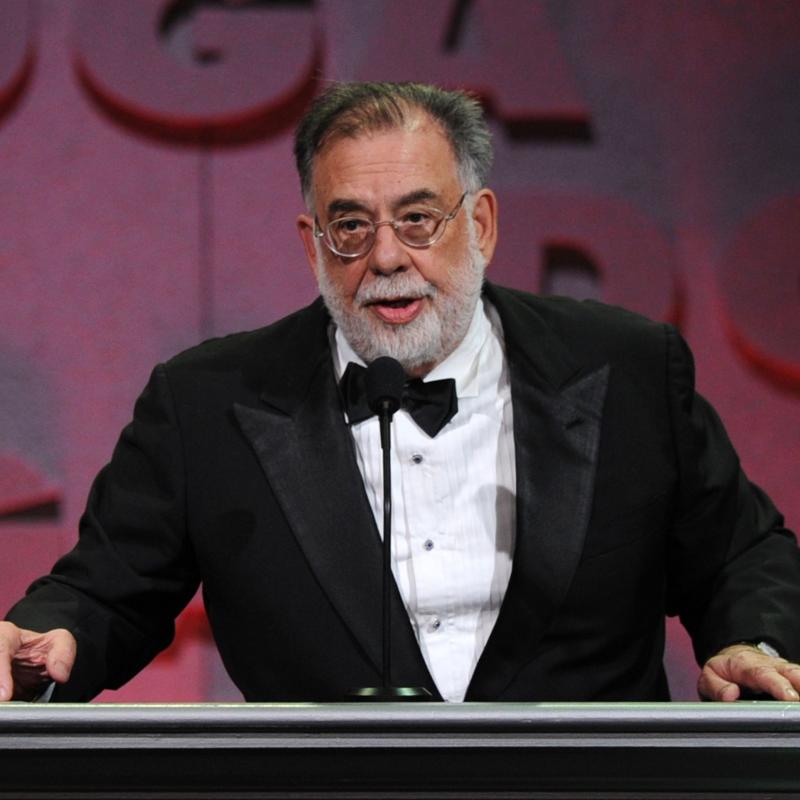

Director, writer, and producer Francis Ford Coppola. A five-time Oscar winner, Coppola is known for such films as "Apocalypse Now," "American Graffiti," and the "Godfather" trilogy. Coppola continues to create in other arenas, such as wine making, and a quarterly literary magazine "Zoetrope" which he publishes. He and his wife have bought and restored the Inglenook wine estate in Napa Valley. Coppola's new film "The Rainmaker" comes out in November.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on October 1, 1997

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: OCTOBER 01, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 100101NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Francis Ford Coppola

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:06

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Today we're going to talk with Francis Ford Coppola about how he started making movies -- movies like "The Conversation," "The Godfather" trilogy, and "Apocalypse Now." We're also going to find out about the projects that occupy him when he's not making movies.

Coppola recently started a literary magazine called "Zoetrope All Story," a tri-annual short story magazine designed to champion new writers and generate ideas for screenplays.

But the big news in his life is the reunification and restoration of his Napa Valley winery. In 1975, Coppola and his wife purchased two-thirds of the Inglenook Winery created by Gustave Niebaum (ph) in 1880. The other third of the Niebaum estate was under corporate ownership. A couple of years ago, the Coppola's purchased the remainder of the estate and began restoring it.

Saturday night, they'll celebrate the completion of the Niebaum-Coppola Estate Winery with a $1,000-a-plate black tie gala. It will include a screening of the silent film "Napoleon."

I spoke with Coppola from his studio, where he's finishing work on his adaptation of John Grisham's "The Rainmaker," which is scheduled to open next month. I asked Coppola first about the winery celebration.

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA, FILMMAKER, PUBLISHER, WINEMAKER: I thought: What could be the biggest show and the most wonderful family event that I could create? And of course it made me think of the film Napoleon, which our company first brought to the public with a full symphonic orchestra, with the music composed by my dad Carmine Coppola.

And I thought: imagine if we restore this castle, and there outside under the stars put up the three screens and battery of projectors that it takes to put it on, because as you know, it's in a three-screen format, and get the full symphony orchestra and come up with a Napoleonic feast, you know, like a eight, 10-course feast with some of the rare wines from our -- from Ingle -- from our cellar that was the old -- we still refer to it as the "Inglenook Chateau" because it says it in the stone, and I couldn't take it off.

And the great rare wines and cigars, and just kind of do a family event-grand opening to the best of our ability. And Marvin Shankin (ph), who's our co-host, we offered it -- it has two fine charities that will benefit from the net proceeds and it's $1,000 a person for a kind of event of a lifetime.

GROSS: So what wine will you be serving at your opening party?

COPPOLA: We're going to introduce -- we're going to introduce the 1993 Rubicon, which -- it'd be the debut of that wine. And then the whole evening will be from the library of the estate. We're going to have a in magnum for the main dinner the '79 Rubicon, which is my -- my -- you know, it's the oldest of our Rubicon, and many other actual wines that come from the estate itself.

GROSS: Talking with you about wine makes me think of food, which also makes me think of scenes in the Godfather, particularly one scene that I just wanted to ask you about related to food.

You know, throughout the Godfather, there's always people cooking pasta and sauces, but there's one scene where Hyman Roth, the Jewish gangster played by Lee Strasberg, is -- he's at home and Al Pacino has just come to visit him. And so, Hyman Roth offers him a can of tuna fish.

That's -- you know, it just struck me as so funny after all of this, like, lavish attention to sauces and pastas, the "would you like some tuna fish?" -- tell me about that scene.

COPPOLA: Yeah, I remember that scene, and we tried as much as possible to make that setting, and Roth's wife I remember came in. She did -- bring them little tables and bring them tuna fish sandwiches.

GROSS: Just the little folding tables.

COPPOLA: Yeah, they were watching baseball. I actually like tuna -- a well-made tuna fish sandwich is a great thing.

GROSS: OK, so you didn't see that as being some kind of contrast in cultural food styles?

COPPOLA: Well, for sure, you know, definitely, but I, you know, I like foods of many cultures, and a tuna fish sandwich, sometimes, watching a ball game is a very -- glass of beer, too -- it's a great -- it's a great option that we all have.

GROSS: OK. Francis Coppola is my guest. And you know, you have a couple of new projects going now in addition to a forthcoming movie. You know, there's the winery, and you also have your Zoetrope literary journal. It's a short story journal that I believe the function of it really is to be a kind of testing place for stories that might lead to interesting screenplays.

COPPOLA: Well, you know, obviously we would be thrilled if a wonderful short story was published in the magazine that could be a movie, but that's not what we -- what the editorial mandate it. They're looking for really, you know, great writing and writing that is about contemporary life, and with characters and situations and classic -- kind of classic stories.

And most of the ones we choose issue after issue are really not immediately translatable into film. We're more interested in setting up a short story magazine that just has great, great short fiction and hopefully new voices and real voices, because motion picture methodology for generating scripts is, you know, so small and insular that it -- I thought it would be very stimulating to have a magazine that really reaches out to writers all over the country and the world, for that matter, and just good short fiction without the tedious and unnecessary mechanism of a screenplay.

GROSS: You've said: "I've never met a person in the film business who enjoys ridding (ph) a screenplay." Why not?

COPPOLA: There's -- firstly it's the form. The screenplay form really is not a legitimate literary form. It's like an architectural drawing to put down in a very clear way the givens of the script so that the production people and the art department can very easily know whether the scene is inside or out or what type of camera view might be appropriate.

It's -- in other words, in a large part it's a kind of technical blueprint, and very often because now writers think that they have to write a screenplay, they go out and they buy a copy of a screenplay or they read a book about the format. And so, they sort of ape what these technical format is.

What happens is the story and the characters start to get lost, and very often the story and the character isn't there, and the format of the screenplay sort of hides that fact. And so I thought that, you know, why should writers be working in a screenplay format -- something that can be done much much later when the film is trying to be broken down and budgeted to really be done.

But if the writers write in a story format -- a short story format -- they can really focus on the character and the theme and the plot. And therefore, it's much, much, more enjoyable for a person who's reading and trying to get into it.

GROSS: I'm curious: did the Godfather look like a good screenplay before it was made into a movie?

COPPOLA: Well, the Godfather screenplay was made from the novel, and really I directed the movie as much from my annotated novel. I used to schlep around this big thick loose-leaf, I don't know -- people who've worked in theater know how you make a "prompt" book, and you actually cut the pages of the text out and so that you can put all the notations on bigger, loose-leaf pages. And that's what I had done.

And I really -- I really directed the movie from the novel, but -- and I did write the screenplay, but that -- that really, I mean, honestly speaking, no director ever looks at the screenplay and says: "oh, it says a close shot here. Let's now do a close shot."

So it really is a -- it's a false methodology.

GROSS: Early in your movie career, you were -- before you were directing, you were writing screenplays and doing rewrites of other screenplays, being like a script doctor. Were there principles that you learned or you figured out early-on that you think still work?

COPPOLA: Well, usually on a technical sense, the script in question sort of starts really 20 or 30 pages after the screenplay, or when it's shot, the movie does. And so one of the quick panaceas that the old, you know, heads of studios and moguls used to do and that I have myself -- found myself doing, is you sort of try to look to the script to where really something seems to be happening and things of interest are starting to coalesce, and sort of delete everything before that.

GROSS: My guest is Francis Ford Coppola. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

Francis Ford Coppola is my guest, and he's now celebrating the reunification and restoration of his winery. I'm interested in some things about your family. I think it was your maternal grandfather who actually owned several movie theaters. What years did he own them? Were you alive?

COPPOLA: No, this would be really in the '20s, I would guess, and in fact they not only owned some theaters, and theaters that catered pretty much to Italian-American audiences, but they lived on top of it, and so all the family would have different jobs.

And my grandmother would take the tickets and the younger mischievous brother Victor -- you know, people in those days used to put their babies in the lobby, and so that he would walk through and say: "baby crying, baby crying." And you know, they would really run these little theaters.

And then from that, he actually began to go to Italy and acquire some films for Italian-American distribution. And his company also -- he did music rolls 'cause primarily he was a songwriter and a composer, and a wonderful one, I think. And his music roll company was called "Paramount" -- Paramount Music Rolls.

And some of his friends in that time, in the '20s, were involved in -- becoming involved in a movie studio and as the story goes, they were talking to him and looking for a name, and he suggested: "we'll call it 'Paramount' -- Paramunto" (ph) -- and that was Baliban (ph) and Katz, who later were the partners in what later became Paramount.

GROSS: That's quite a brush with early movie history.

COPPOLA: Well, I have on the other side another interesting story. My other grandfather, Carmine's -- Carmine Coppola's grandfather Agostino (ph) was a very fine, you know, engineer and tool and dye maker -- made mechanical things. And he was called upon to engineer and build a new device that turned out to be the Vitaphone, which was the first sound-talkie movie that -- when they made "The Jazz Singer" with Al Jolson it was -- and there, it's in our museum. There's a beautiful museum in the winery and there's a picture of him with the Vitaphone that he's just built.

GROSS: Can you sing a verse of a song that your grandfather wrote?

COPPOLA: Well, sure, I'll always sing for you. In the Godfather, there was a whole sequence in a little Italian-American music hall where they sang a song that was called "Sens a Mama" (ph), and it went something like: "Sens a mama, a quantifore so parola encore. Sens a... " (ph) -- it's all about crying because you he ran off with a sort of a woman of no account, and then his mother died.

GROSS: So, that was your grandfather's song?

COPPOLA: Yeah.

GROSS: Oh, that's great.

COPPOLA: That's a Neapolitan song.

GROSS: Hmm. So I think it was your grandfather who gave you, what, a 16-millimeter projector when you were a boy?

COPPOLA: That's right. I -- in the '49 I had polio and I was paralyzed for a year, and he did bring me a, you know, a kind of 16-millimeter projector. It was a young people's projector. It wasn't a, you know, serious -- it was a real working 16-millimeter projector, but it was, you know, of toy quality, but I used to -- I certainly loved that.

GROSS: So, what did you project in it?

COPPOLA: Well unfortunately 'cause it was 16 millimeter, there were only the couple of little film clips that I had. Most of what film I could play with was in eight millimeter, and there I had a number of cartoons and some home movies, and also my father had a -- one of the very early tape records, the Ecor (ph) Home tape recorder, and I had it by my bed when I was in that period of being paralyzed, and I used to try to make sound tracks and synchronize them and make them play in sync with the movies.

GROSS: And what would be on the sound track?

COPPOLA: Well, it would be stuff like: "well here we go. We're very dah, dah, dah, dah, dah. Hi Mickey! No, no, no. Watch out the fire."

Things like that.

LAUGHTER

GROSS: So how paralyzed were you?

COPPOLA: Well, I couldn't walk and I couldn't move my left arm.

GROSS: So, you spent a year basically away from the rest of the world.

COPPOLA: I was in a bedroom on the second floor. You know, in those days, people were very, very frightened of polio as a children's contagious disease, so I didn't certainly see any kids. I don't know -- I saw my brother and my sister and I had a television. One of my great frustrations, of course this is before remote control, was that I was unable to get up to change the channel.

But I had my favorite shows. There was one called "The Children's Hour" that Horn and Hardart (ph) used to do with lots of talented kids singing and dancing. I loved that, and some puppet shows.

GROSS: So, did you have any sense at this age that you actually were getting serious about movies?

COPPOLA: No, I didn't have a very, you know, important view of myself. I was a -- you know, I had been always -- moved many, many schools so I always kind of was a little bit of a loner, and I had an extraordinarily talented and, you know, really a kind of winner older brother who was very kind to me, but pretty much was the star of the family.

And so, I never thought of myself as -- wasn't good at school and I wasn't particularly as, you know, my family was very good looking, all of them. And you know, I was sort of -- I was the affectionate one. I wasn't as good looking as the others.

GROSS: It must have been interesting for you to eventually go from, you know, being paralyzed for a year alone at home in your bed, to, you know, being such the center of attention and so famous.

COPPOLA: It was totally an accident. It happened because I, you know, sort of was a little bit of a boy scientist, and I was very interested -- I used to stay by myself in the basement or the garage, whatever, since we moved a lot, whatever little shop I could set up. And it was my interest in science and electricity and, you know, that got me kind of working on lights and on theater.

And then I think my older brother was a writer and because of him I heard about things related to literature, and you know, I pretty much wanted to emulate him.

So, the combination of being interested in stories and literature and lights and theater and I must say girls, because the girls who were at the theater department or the football team.

GROSS: Right.

COPPOLA: So I wanted to -- you know, I always was a little bit of an outcast socially because I was the new kid, and I felt if I could hang out at the theater, and of course theater always needs volunteers, and if I was willing to, you know, work and unravel the cable or help build the sets, I could be included in the group.

GROSS: Your father, Carmine Coppola, who wrote music for The Godfather and for the restoration of Napoleon was, you know, a professional musician throughout his life and certainly, you know, while you were growing up. He was a flautist with an orchestra. He played for a while with Radio City Music Hall accompanying the Rockettes.

What were some of the things that seemed really exciting to you about his work?

COPPOLA: Well, you know, the most dramatic part of that period as a little child was that he was the solo flutist for Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra. So all during the time that I was a small child, it was a very prestigious and we were -- occasionally there'd be articles in the newspaper about him.

And so, we knew there was something important going on. Although when I was really little, I used to go around telling everyone that my father was a magician because I had heard he was a magician, but I got it wrong. He was a musician.

LAUGHTER

I remember one incident that is very vivid in my mind. They took me to the studio in radio -- in RCA studio 8H where the big orchestra, and Toscanini with his white hair and black turtleneck was. I was brought as a five-year-old in that little glass booth, and I was very intrigued because there was a knob in the booth, and when you turned it all the way to the left, you would hear the orchestra. And when you turned it to the right, you couldn't hear the orchestra.

I think that's when I first realized as a concept that sound and picture are not necessarily connected. But my dad was more ambitious as a composer. He went to Radio City really as the chief arranger.

GROSS: Ohh.

COPPOLA: He didn't -- he didn't -- when he was a young men, he had played there, as did his brother who later became a conductor there. And so us kids, my brother and I, were brought into the back of the stage at Radio City and were shown and sort of had a run of it in a way and could see the incredibly theatrical mechanisms that are back there, and got to go there a lot, and that's one of the reason when we first -- when I thought of doing Napoleon with a symphony orchestra, that -- my dream was to do it at Radio City which, at that time, was under real financial pressure. There were even rumors of possibly decommissioning it.

And Napoleon was the first event done at Radio City -- an outside event that was a tremendous success, and put them on the track of doing outside events, which saved the music hall.

GROSS: I know you were a theater major as an undergraduate. Did you perform in musicals? Did you sing and dance?

COPPOLA: I did a few times. My brother's wife was our choreographer, and I would build the sets. And you know, again, I loved the theater experience of being one of the gang and getting to go with them all after -- and have coffee. And I did sing and dance in "Of Thee I Sing" and the one, let me see, what was that called? Oh, there was a '40s musical about kids. I forget the name now.

GROSS: Two of your movies have been war movies -- "Patton" and "Apocalypse Now." Did -- were you ever drafted?

COPPOLA: No, but one of my school experiences was at a military school. I was at New York Military Academy in high school for a couple of years. And of course, I played in the military band. But I was a full-out cadet and so I knew a lot about, you know, really in a funny way, cadet life, which of course is -- it was a place -- that place up there right next to West Point. And I was very good at drill and I knew all about military organization and stuff like that.

GROSS: So you liked it?

COPPOLA: I did like it. After a while, I felt a little isolated there. When an older roommate graduated, he was someone who was, you know, reading James Joyce's "Ulysses," and he was a kind of pretty interesting fellow. He was also the only Jewish guy in the school, and I admired him.

And then the next year, I kind of felt very isolated and wanted to do interesting things with the theater group there, and they didn't want me to, and I finally ran away.

GROSS: Ran away from school?

COPPOLA: Ran away from military school.

GROSS: Oh, my gosh. Were you caught?

COPPOLA: Well, I did it very effectively. I just called a cab.

LAUGHTER

GROSS: Well, what happened?

COPPOLA: I wandered around New York, scared to go home. Of course, my father was on the road with a Broadway show -- with a touring show. And I wandered around New York and I had sold my uniforms to some kind of guy whose brother was gonna come the next year, and I had a couple hundred dollars, and I just -- I sort of lived this very strange, wandering around New York and seeing things I'd never seen before.

And then when I got home to where my brother was living with his wife, he said -- I told him what had happened -- he said: "here, read this book." And I read "The Catcher in the Rye" and I said: "hey, I just did this." I wrote a letter to J.D. Salinger after reading it, and I said in the letter, you know, "I'm 16 and I want to be a filmmaker and I just lived something so much like your book that I know I would do a good job. I wish you please let me have the rights to make Catcher in the Rye."

LAUGHTER

GROSS: Oh, that's a scream. I'm sure you got a lot of response from J.D. Salinger.

COPPOLA: Yeah, zero.

GROSS: Yeah.

Francis Ford Coppola will be back with us in the second half of the show. His new literary magazine is called Zoetrope All Story. His next film, The Rainmaker, is scheduled to be released next month. This Saturday, Coppola celebrates the reunification and restoration of his winery in the Napa Valley.

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Back with Francis Ford Coppola. This Saturday, he celebrates the reunification and restoration of his Napa Valley winery, the Niebaum-Coppola Estate, and his film adaptation of John Grisham's The Rainmaker is scheduled to open next month.

We talked about his latest projects and his early career.

So you -- when you decided you wanted to make movies, you went to UCLA for grad school. Did you think that school would help to a movie career?

COPPOLA: Well, I was a theater major and as I finished college undergraduate, there was that point in which a lot of people chose, you know, are they going to go to the Yale Drama School. And I was already interested in film, having seen the works of Eisenstein and being very knocked out by them. And I liked that I had stayed in my theater background because I worked a lot with actors and acting, and I felt that would be very valuable for the kinds of films that I wanted to make.

And I chose the UCLA film school. In those days it was, you know, kind of the famous one and supposedly the very good one, and then I left and around 1968, went out to California.

GROSS: Your early movies include, you know, on the one hand "The Terror," a Roger Corman Production with Jack Nicholson. And -- oh what's it called with Fred Astaire?

COPPOLA: "Finian's Rainbow."

GROSS: ... Finian's Rainbow, yeah. So you know, the young Jack Nicholson on one hand, Fred Astaire on the other -- a musical on the one hand, and Roger Corman on the other. It seems like an interesting mix.

COPPOLA: Well, that was an interesting period back there in the beginning of the '60s that I was in film school. I was very poor, and I had come from such a wonderful period of working in theater at Hofstra College in the East Coast, and having the chance to direct, you know, original musicals, and I did "Streetcar Named Desire" and I was very -- became, you know, like at schools, there's always the boy wonder who has the keys to everything and runs the drama organization.

So I went from a period of great kind of probably greater power than I've ever achieved in the years later. And suddenly, I was all alone in California in a much more solitary kind of work. The film students at UCLA were all locked in their rooms, you know, using the pecking order of who got the movieola equipment; who didn't.

And it didn't have the warmth and the camaraderie of theater. And so I was very, very depressed and very, very poor. And just started to try to get any kind of work I could. And there's a film that is out that has my credit as the director, called "Tonight For Sure," which was a little nudie film. The truth is that it was a German nudie film and I was hired to kind of do the English subtitles and edit it. And since I was the editor when it came time to put the credits on, I just wanted to see it so I put it "Directed by Francis Ford Coppola," just because I was the one who got to make the decision.

Of course, that's -- for years, people would say: "gee, I saw your first film." And I sort of say: "well, you know, I really didn't make that film. It was made in Germany." But I did put my name on it, so I guess it's mine for historical purposes.

GROSS: However, you did make a couple of other nudies, didn't you? "The Peeper?"

COPPOLA: That was really the one. What I had done is I had made a little short that was just a little, kind of little silent, cute little silent film, like a little silent comedy. And then this company bought it and hired me to integrate my 12-minute film into this really horrible nudie film that they had produced.

And it was -- I was sort of working for this schlock film company, just trying to make, you know, any kind of money. But the funny thing is that since I was the one sort of in charge, I'd always put my name -- I would always get a beautiful name title, just because, I don't know, in those days, it didn't really seem as though the young people were ever going to really get to make film.

Usually, in UCLA, you would end up working for the USIA or do government documentaries. And so, it was a fantasy to see your name as, you know, "directed by." It looked like a dream.

GROSS: And tell me a little bit about how you integrated your 12-minute film into this nudie film?

COPPOLA: Well, it was a short comedy, just a little like "Tom & Jerry" cartoon. And the movie they had made was about a cowboy who falls on a rock and keeps seeing cows as naked girls. And I was really terrible, and my job was to sort of spice up their film. Their film would, like, keep cutting back to this character, and you know, figure out a cockamamie way that it could all, you know, so that -- they bought my film for $500 or something, and they were going to pay me a few hundred dollars if I did it. That's the one that everyone refers to.

GROSS: Where did it play?

COPPOLA: I have no idea, really.

GROSS: What kind of theaters?

COPPOLA: I -- you know, that was the beginning of the soft-porn business. The great film was "The Immoral Mr. Teas" (ph).

GROSS: Right. That was a Russ Meyers movie.

COPPOLA: Right. And so that they began to, for the first time, allow nudity in theaters and that's what these sleazy companies were just trying to do whatever they could to have something.

GROSS: Francis Ford Coppola is my guest.

Since you really like singing and dancing so much, what was it like for you to work with Fred Astaire in 1968?

COPPOLA: Well, it was, you know, he was such an elegant, interesting man. The movie was a bit of a kind of a low-budget. The idea was to take the "Camelot" sets and sort of just fake it. And then they got Fred to agree to be in this old musical, and get a kid who could do it. It was a very inexpensive film.

And of course, I wasn't really -- I at that point wanted to do, you know, serious, original movies, you know, from my own screenplays. But I was so -- you know, I had come out of a musical tradition and I know that -- I thought that gee, Finian's Rainbow has such gorgeous songs. I didn't realize it had the dumbest book, you know.

So I sort of inherited this kind of chestnut, low-budget. But it was a pleasure to work with Fred. He was just a very charming man, very hardworking man and just the sweetest possible person; professional. And I learned, you know, kind of -- many things from him.

And -- but by the time I had had this little stint, you know, kind of in a big studio where I was obviously just a pawn, I very much wanted to get out on the road and make a real personal film, which I did immediately after that. I made a film called "The Rain People."

GROSS: So is that when you knew that you wanted your own production company? That you didn't want to just be within what was left of the Hollywood system?

COPPOLA: Yeah, I think the experience of making The Rain People on the road with our own lightweight equipment, and I had this very young, wonderful assistant, really, who began for the first time in my life to be like a kid brother, who also shared my film school enthusiasm.

We sort of formulated how we could have a film company with this new equipment, and be totally independent, and in fact, be located in San Francisco, which as soon as we got back, that's what we did. And of course, that was George Lucas.

GROSS: Of course, with freedom, with creative freedom comes responsibility, and in this case the responsibility of running a production company, dealing with all the finances. I mean, how did you feel about taking that on? It certainly can take up time and distract you from the actual act of movie-making.

COPPOLA: Well, I had lots of experience running the student organizations in the theater department. So in a way, this new company which of course was called "American Zoetrope" and back in 1969 was very much like the little empire I had at school.

And I brought, you know, that and of course George was very young, so he hadn't worked in theater and he was much more interested in, you know, cinema and editing and graphics. And we made a wonderful combination.

And in fact, Zoetrope was the first independent operation that filmmakers had started where they own their own facilities and their own sound mixing equipment, which is why the soundtracks that started to come out of our films in San Francisco really changed the definition of what Hollywood soundtracks were.

GROSS: How?

COPPOLA: Well, we became involved in -- we believed firmly that the sound was 50 percent of the cinema experience. And since we owned the mix studio, we began to do extremely beautifully designed soundtracks. In fact, the phrase "sound designer" was created by us so that we could employ Walter Mirch (ph), who wasn't in the union.

And movies like Apocalypse or "Star Wars" really began to feature these extraordinary artistic sound tracks, many of which were done by Walter.

GROSS: You know, you had this almost like psychological insight into how sound is perceived.

COPPOLA: Well, you know, now movie soundtracks, of course, have, you know, evolved and now they're too loud and too assertive. But we always considered that the sound was half the movie experience, and so we gave it a lot of importance. You know, but that was -- we did many things. We did many innovative things in those periods as the early American Zoetrope, and lots of traditions -- some good and some bad -- were started by us.

GROSS: What do you think is a bad tradition that you started?

COPPOLA: Well, we were the first company ever to put the entire crew on the end credits.

GROSS: Oh, wow. You know, somewhere -- the director of "L.A. Confidential" -- we were just talking about credits at the end, you know, 'cause one of the actors' parents was a caterer back in Australia. Anyways, so we were talking about "do you want to see all those credits at the end or not?" So what do you think of that? You think -- this is especially true in any film that has animation or special effects. The credits last forever.

COPPOLA: Yeah, I much, much prefer the old system -- of course, now the guilds won't let you do it -- in which you used to see the credits quickly and, you know, you'd have the photographer and the editor and the composer might be on the same card, and now everyone has to get a separate card.

It's just absurd. I mean, now it's five minutes of credits, you know. We did it because we were young and poor, and we were very appreciative. We had a small crew and they'd all kind of gone through thick and thin for us, so we had the idea of putting them all on the end credits -- in gratitude, really, but that started a precedent.

Also we were the first company ever to give crew jackets as a present to the crew -- another tradition which is overworked. We were the first company to ever call a movie "Part II," you know, so we were always innovative.

GROSS: My guest is Francis Ford Coppola. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

Back with Francis Ford Coppola.

Michael Schrago (ph) recently had a very interesting piece about the making of The Godfather. This is in the New Yorker. And he mentioned that the reason why you made The Godfather is because your film production company was in desperate need of money. You had creditors knocking on your door. And so, you might not have ever made The Godfather if you didn't really need money very badly.

COPPOLA: Well my dream as a young person was really to have a career not all that different except in the type of film from Woody Allen. I was always one of the directors who was a pretty good screenwriter, and I always dreamed of writing personal screenplays and just making those as my career.

But you know, The Godfather sort of was like really changed my life in many ways. I did do it because we were broke, and of course we've always been broke. We've always been independent. We've never had anyone sponsor us or, you know, ally with us.

And then later when we started to get really powerful, then people feared that we were going to demonstrate that filmmakers really didn't need that whole upper apparatus that basically runs everything and takes all the money just because they provide the finance, you know.

So you know, I -- the issue of independence and trying to reconcile that with being -- with having money is always a tough one.

GROSS: What was it about The Godfather that made you think: "I don't really want to do this, but I'll do it 'cause I have to."

COPPOLA: Well, I'd -- when you read the book, the original book, with the story of the father and the three sons, which became the core of the film, was only one of a number of, you know, plots in a big thick book. You know, there were stories about a kind of -- you know, they were more salacious, more kind of bestseller kind of junky parts, which Mario no doubt wrote to make a bestseller.

And I -- and when I first read it, I kind of, you know, as I said, I wanted to write, you know, personal films and artistic films, and I felt that there was a -- you know, it was like a Harold Robbins book or -- not to put Harold Robbins books down.

But then only later when I began to work on it, I realized that the core of the story -- if you just eliminated everything else -- was like a very classic, beautiful story of a king and his sons. And I began to become interested on that level.

GROSS: It seems to me you've worked with some -- you've just, like, discovered or you know had really early-on some actors who just became, you know, wonderful -- Pacino, DeNiro, Robert Duvall, Gene Hackman, you know, in The Conversation. Is that something you've really prided yourself on, as having a sense of...

COPPOLA: Oh, yeah. You don't have to stop there. I mean, we gave the first roles to many of the big stars...

GROSS: Nicholas Cage's early work is in your movies.

COPPOLA: Mm-hmm. Nicholas Cage did three or four movies. Harrison Ford, Tom Cruise and Matt Dillon -- I mean, just this enormous list of people. Now coming even more recently, people who were in (unintelligible) -- Jim Carrey (ph), Helen Hunt. I mean, most of the important people today in Hollywood worked through opportunities given by American Zoetrope.

GROSS: So...

COPPOLA: Why?

GROSS: Yeah, I'm just -- I'm sure you don't have like a system for discovering actors, but if there's anything you could share about that.

COPPOLA: It's that I truly and sincerely believe that all cinema, all theater comes from the two main ingredients: writing and acting. And therefore, you know, we love writers and I love actors and give them all importance and all consideration and all benefit of the doubt.

And if you do that -- if you have that attitude -- you can't fail but, you know, like uncover wonderful talent.

GROSS: Compare for me if you would the joys and headaches of filmmaking versus winemaking.

COPPOLA: They're very similar. Both are very much rooted in the source material. In winemaking, it's the land. It's the micro-climate of the land; the unique characteristic of the land that produces the grape. So you can make -- if you have great grapes, which come from great land, you can make mistakes with it, which you can kind of work with through refining and editing.

In film, it's the source material. Again, it's the writing and it's the acting, and if you have that -- if you have that extraordinary blessing of the talent in the writer and in the actor, then again you can make mistakes with it, but you might be able to work with those mistakes through editing and fining.

And then both processes go through a finishing process which now we're doing on The Rainmaking where -- Rainmaker -- John Grisham's Rainmaker -- where we're actually, you know, blending all the music and sound effects and different elements into a finished product with finesse.

And you do that when you finally fine the wine and finish the wine and put it in the bottle and then care for it in the bottle for a number of years. So they're very much parallel art forms.

GROSS: Is The Rainmaker an American Zoetrope production?

COPPOLA: It's a co-production. It's a Constellation Films in association with American Zoetrope.

GROSS: And tell me why you wanted to do this movie?

COPPOLA: Well, you know, I -- it's so tough for a director today. I mean, I'm always trying to work on my own work, and of course the demands of supporting a family, and in this case you know, finishing up my winery makes it desirable to occasionally get a job.

And usually the kinds of jobs that a director can get, you know, are not too interesting or very much the same. They're big formula kind of things. So to get a real book, this John Grisham book that was about something interesting; that viewed the kind of sleazy side of the legal business from the eyes of a young law student -- I just felt it had rich characters and, you know, I was grateful to have a piece of work that wasn't some kind of silly formula script with everything blowing up. And I was just very grateful to get the job, to be honest with you.

GROSS: One last question: will the characters be drinking wine in The Rainmaker?

COPPOLA: In a scene or two...

GROSS: OK.

COPPOLA: ... in a scene or two.

GROSS: Well, I want to wish you a happy opening for your winery.

COPPOLA: Thank you. Thank you.

GROSS: And congratulate you on the restoration.

COPPOLA: Thank you.

GROSS: Francis Ford Coppola celebrates the reunification and restoration of his winery, the Niebaum-Coppola Estate Winery, this Saturday. His next film, an adaptation of John Grisham's The Rainmaker, is scheduled to be released next month.

From the soundtrack of "Godfather II," here's Sens a Mama -- the song written by Coppola's grandfather.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, ORCHESTRA PERFORMING "SENS A MAMA")

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Francis Ford Coppola

High: Director, writer, and producer Francis Ford Coppola. A five-time Oscar winner, Coppola is known for such films as "Apocalypse Now," "American Graffiti," and the "Godfather" trilogy. Coppola continues to create in other arenas, such as wine making, and a quarterly literary magazine "Zoetrope" which he publishes. He and his wife have bought and restored the Inglenook wine estate in Napa Valley. Coppola's new film "The Rainmaker" comes out in November.

Spec: Movie Industry; Francis Ford Coppola

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1997 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1997 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Francis Ford Coppola

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: OCTOBER 01, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 100102NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Time Out of Mind

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:55

TERRY GROSS, HOST: Bob Dylan has a new album out, "Time Out Of Mind" -- his first collection of new material since 1990. And it heralds a new period of activity and recognition for him.

After surviving a serious heart ailment earlier this year, Dylan resumed a nationwide tour that's been getting great reviews, and which recently included a performance before the Pope.

In December, he'll be given an award in Washington for the Kennedy Center Honors.

Rock critic Ken Tucker says Time Out Of Mind contains some of Dylan's strongest work ever.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "TIME OUT OF MIND")

BOB DYLAN, SINGER, SINGING: The air is getting hotter

There's a rumbling in the skies

I've been wading through the high muddy water

But the heat rises in my eyes

Every day your memory grows dimmer

It doesn't haunt me like it did before

I been walking through the middle of nowhere

Tryin' to get to heaven before they close the door

When I was in...

KEN TUCKER, FRESH AIR COMMENTATOR: The Bob Dylan as he allows himself to be revealed on Time Out Of Mind is a man out of time -- in self-imposed exile from rock trends, and all the wiser and stronger for keeping his distance from their energy-sapping fickleness. Like his son Jacob but in a different sense, he's a wallflower at the party of pop music.

The music on this album sounds ancient, and yet just written -- full of ghosts and dreams of mortality. In the song I just played, he's trying to get to heaven before they close the door. But for a fellow almost gleefully contemplating his afterlife, Dylan remains Earth-bound in love. He offers a shockingly bitter take on it with the song "Lovesick" and then turns around to mix romance with regret on "Til I Fell In Love With You."

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "TIL I FELL IN LOVE WITH YOU")

DYLAN SINGING: Well, my nerves are exploded

And my body's tense

I feel like the whole world

Got me pinned up against the fence

I been hit too hard

I seen too much

Don't think you can heal me now

But you're tough

I just don't know what I was gonna do

I was all right 'til I fell in love with you

TUCKER: Time Out Of Mind is produced by Daniel Lanoir (ph), who as he did on the 1989 album "Oh, Mercy," keeps Dylan's voice, the rasp of a cryptkeeper, prominent while surrounding it with eeriness. Lanoir gives a song called "Cold Irons Bound" a herky-jerky shuffle beat, for example. He creates a rhythm that skeletons might dance to in a graveyard, using a few discarded bones for percussion.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "COLD IRONS BOUND")

DYLAN SINGING: I'm beginning to hear voices

And there's no one around

Now I'm all used up

And the fiends have turned 'round

I went church on Sunday

And she passed by

Why my love for her

Is takin' such a long time to die

God, I'm waist deep, waist deep in the mirrors

It's almost like, almost like I don't exist

I'm 20 miles out of town

Cold irons bound

TUCKER: Time Out Of Mind builds to an extraordinary piece called "Highlands" -- a 16 1/2 minute ramble. Crooning in the voice of a guy who's a little hard of hearing, he says: "I'm listening to Neil Young. I gotta turn up the sound." He's decided he's a big loser in the game of life.

Dylan goes for a stroll that turns into a dream, or maybe a nightmare. Out on the street, nobody's going anywhere, he says. A restaurant he enters is empty -- must be a holiday. The speaker in Highlands comes across as zonked, out of it, and perfectly resigned to it. The song, pushed along by Jim Dickinson's (ph) loping electric piano, gathers a cumulative force in its atmosphere of confused sadness. Here, he's just warming up to his subject.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "HIGHLANDS")

DYLAN SINGING: I don't want nothing from anyone

Ain't that much to take

Wouldn't know the difference

Between a real blonde and a fake

Feel like a prisoner

In a world of mystery

I wish someone would come and

Push back the clock for me

TUCKER: With its cranky, suspicious yet resigned view of life, Time Out Of Mind sums of Bob Dylan the way "Bringing It All Back Home" and "Blood On The Tracks" once did. Dylan sounds lively, even playful -- in no way is this album a downer. It sounds as if at 56 he can't wait to be a full-fledged old codger -- a decorated codger to be sure. In December, he'll be a Kennedy Center Honoree, along with Charlton Heston, Jessye Norman, Edward Vilella, and Lauren Bacall.

Gee, at the State Department dinner, do you think he'll dedicate Cold Irons Bound to Al Gore?

GROSS: Ken Tucker is critic-at-large for Entertainment Weekly.

Dateline: Ken Tucker; Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest:

High: Rock critic Ken Tucker reviews Bob Dylan's new release "Time Out of Mind."

Spec: Music Industry; Bob Dylan; Time Out of Mind

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1997 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1997 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Time Out of Mind

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.