From The 'Fresh Air' Archives: Eddie Bunker, Who Honed His Writing Craft In Prison

Bunker, who died in 2005, spent 18 years in prison before becoming a successful writer. He co-wrote the screenplay for the 1985 film Runaway Train, which helped launch the career of actor Danny Trejo.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on March 14, 2018

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

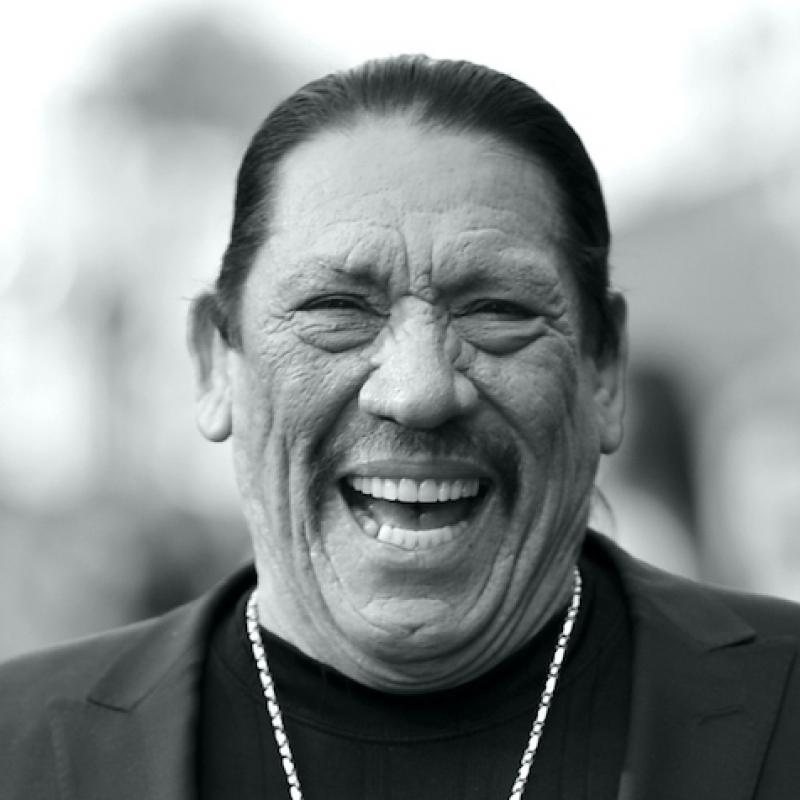

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. My guest, actor Danny Trejo, came of age in the California prison system doing time in a juvenile detention center as well as San Quentin, Folsom and Soledad on charges relating to drugs and robberies to buy drugs. As an actor, he's best known for his menacing roles like a character who was nicknamed after his weapon of choice.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "GRINDHOUSE")

UNIDENTIFIED NARRATOR: They called him Machete.

GROSS: The movie "Machete" began as a fake, ironic movie trailer in the Quentin Tarantino-Robert Rodriguez film "Grindhouse."

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "GRINDHOUSE")

UNIDENTIFIED NARRATOR: Set up, double-crossed and left for dead. He knows the score. He gets the women.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #1: (As character) He's bad.

UNIDENTIFIED NARRATOR: And he kills the bad guys.

GROSS: A few years after the fake trailer, Rodriguez decided to actually make the movie "Machete" starring Trejo. Danny Trejo's other best-known role was in "Breaking Bad." He played Tortuga, who winds up being decapitated with his head mounted on a living tortoise - long story. But if you saw "Breaking Bad," you remember that scene.

I love how Trejo's career was described by Amos Barshad writing in the magazine Grantland. Quote, "Trejo has been stabbed, shot, maimed, crushed, hung, choked, decapitated and blown to bits. He's had hypodermic needles jabbed into his neck. He's had a power drill run through his brain. Charles Bronson and Robert De Niro have killed him. Stone Cold Steve Austin and 50 Cent have killed him. Mickey Rourke has killed him twice," unquote.

Trejo still returns to prisons to talk with inmates. Now he's the producer of a documentary called "Survivor's Guide To Prison," which focuses on injustices within the criminal justice system and highlights the cases of two men who spent decades behind bars for murders they didn't commit. Trejo is one of the people who speaks in the film, which is now streaming on Amazon and iTunes. Danny Trejo first started using drugs when he was 8 years old.

Danny Trejo, welcome to FRESH AIR. You said it was your uncle who introduced you to drugs...

DANNY TREJO: Yeah.

GROSS: ...And to crime. What did he introduce you to, and why did he do it?

TREJO: Well, you know, at first, it was marijuana. And this was in the '50s. Now, you ask people - ask, well, was weed a gateway drug? And I say, I don't know. The only thing I know is that everybody that I knew in prison that did heroin, that did cocaine, that did PCP, that did acid started with marijuana.

GROSS: Did heroin become your drug of choice?

TREJO: Yes.

GROSS: How long did it take for that to happen?

TREJO: My uncle gave me a fix when I was about 12. And...

GROSS: How can he do that? I mean, that seems like...

TREJO: Well, I - in his...

GROSS: It's such a really terrible thing to do.

TREJO: I know. In his defense, I've got to say that I threatened to snitch on him if he didn't give me some (laughter). I caught him fixing. And I said give me some, and he said no. Give me some, or I'll tell. So basically he gave me some. And I was off and running. I just hung out with my uncle from there on.

GROSS: How did you - was it through your uncle that you continued to get drugs once you were addicted? I mean, a 12 year old...

TREJO: Yes, yes, no...

GROSS: ...Doesn't have the means to support a habit.

TREJO: It was basically through my uncle. I stayed, you know, around him a lot. And then I knew all the people he knew and - so yeah.

GROSS: Where were your parents while this was happening?

TREJO: They were, you know, trying to be positive Republicans, you know? I mean, they wanted to, you know, have a home and a camper and a Cadillac. And they were great parents. But the reality was my dad was, you know, hard worker, hard worker. I've got to, you know - I've got to get ahead. We've got to pay these bills. And my mom was - I got to clean this house. We have to start dinner at 1:30 because your dad gets home at 5, you know? And that was the way it was. And I was an only child, so that's just the way it was.

GROSS: But it sounds like maybe you were much more influenced by your uncle than by your parents.

TREJO: Completely.

GROSS: So were your parents not paying enough attention to you...

TREJO: That's sound - don't...

GROSS: ...Or were you just not paying enough attention to them (laughter)?

TREJO: That sounds, you know - that sounds so like, oh, my mommy didn't pay attention. No, you know, I wanted to be left alone.

GROSS: My impression was that you didn't want the life, that kind of stable...

TREJO: Well, I don't think...

GROSS: ...Life that they wanted.

TREJO: Oh, God, I don't think it's up to a kid whether he wants to be - I think it's up to parents. Like, no, I'm butting into your life, you know what I mean? And I stayed in my kids' business. And even though - with all the knowledge I had and with everything that I knew, my kids still wouldn't use drugs. But thank God they knew where to go when it was time for them to - wait a minute; I've had enough.

GROSS: In movie roles, you're famous for being really tough and very menacing when you need to be.

TREJO: Yeah.

GROSS: Was that an asset for you in prison? Was - is that something...

TREJO: Absolutely.

GROSS: ...You knew how to use when you were in prison?

TREJO: Absolutely. There's two types of people in prison. There's predator and prey. You have to decide every day which you're going to be. And it's that simple. The more intimidating, the more people you have behind you - 'cause it's not a - I have never seen a fist fight in prison. Do you understand?

It's so much easier to stab somebody and walk away than it is - 'cause if you get in a fight, if I sock you, you're going to sock me back. And then we're going to tussle. And then they're going to shoot us. But if I walk up behind you, stab you three times and walk away, I'm not going to get caught. And that is the idea - not to get caught. You've done something wrong, and this is what happens. That's why in prison, they say the bottom line to any argument is a murder.

GROSS: So how did you turn yourself into a convincing predator so that you wouldn't be prey?

TREJO: Have you ever seen me?

GROSS: (Laughter) Yes I have. That's a good answer.

(LAUGHTER)

TREJO: I'm here to tell you. So like, that's how I got in the movies, you know, like...

(LAUGHTER)

TREJO: But you go to prison the first time because now it's so easy to go to prison your first time arrested. And so now when you go to prison, all of a sudden, you have not been brought up in this lifestyle. So if you were in juvenile hall, in youth authority and then in prison, that means you went to prep school. You went to graduate school. Now you're in the university. And you know how to behave. You know what to do, what not to do. If you're there for the first time, you're walking around - ask God, can you help me? Hey, buddy, can you tell me where the pool is? So it's like all of a sudden, you're lost. You're not in your element.

GROSS: So you came up through the system, so you knew.

TREJO: Yeah.

GROSS: You know what to do. OK, so something that really helped you in your later life as an actor - it helped get you into acting - is that you became a lightweight and welterweight champion in prison. So...

TREJO: Yeah, boxing. That was my uncle again. My uncle started boxing in Golden Gloves, and I was his sparring partner - punching bag. And so I either had to learn how to fight or get my head kicked in. And he - you know, he taught me how to fight. So basically anything you're good at, you can use. Like, some people are real good at writing letters. Well, that's a way to protect yourself. Some people are real good at fighting. That's - you know, boxing I think kept me out of a lot of trouble.

GROSS: What happened to your uncle? Did he do time, too? And is he still alive?

TREJO: Oh, yeah, yeah. He did about 20-something years, and then he overdosed.

GROSS: Why do you think you were able to give up drugs and stay out of prison eventually? Like, how old were you when that happened, and what was the turning point for you?

TREJO: Cinco de Mayo in 1968. Me, Ray Pacheco, Henry Quijada - I can say that because I think they were both killed in robberies. We were involved in a prison riot. I went to the hole and expected to go to the gas chamber.

GROSS: What were you accused of?

TREJO: Inciting a riot. And by the grace of God - I can remember saying, God, if you're there, if you let me die with some dignity, I will say your name every day, and I will do whatever I can to help my fellow man. And really I thought it was just going to be a couple of years. Then they were going to kill me. But it wasn't (laughter). It's like he fooled me and gave me the rest of my life.

GROSS: Was it hard to learn kind of emotional control, like, controlling anger and things like that coming of age in prison?

TREJO: Anger is probably something you don't have in prison. You don't have anger. You can't afford to get mad. If it is worth your time, then you go directly to rage.

GROSS: Oh, I see what you're saying (laughter).

TREJO: You understand?

GROSS: Wow, OK, yeah.

TREJO: You know, I can remember. It's like, I've watched attorneys argue, and I'm waiting for somebody to get socked, you know? Wait a minute. You going to sock him, you know? And - because in prison, you don't get angry, you know? You go directly to rage - whatever it is - because that's your defense. The bottom line to an argument is a murder. So if you say something to me that I think is an attack or belittling, I have to think, is this worth killing him over?

GROSS: It's quite an equation to have to go through all the time.

TREJO: Well, it only takes a split second.

GROSS: So when you got out of prison, you couldn't go from zero to rage...

TREJO: No.

GROSS: ...Because, you know, murder isn't the bottom line when you're - (laughter) it's not the way to settle an argument when you're out of prison.

TREJO: I - yeah, but it...

GROSS: Rage is not - you know, it's not always the most effective way of going about things, particularly out of prison. So how did you know - learn how to control that?

TREJO: I think I had a really good support system around me. And, you know, I think that's the main thing coming out of a prison - is, like, if you're by yourself, then you're still alone. And it's like I had a great support system, which was a 12-step program. And the people that I was around knew about rage. They knew about the bottom line to an argument's a murder. So I just - was just real choosy about the people I associated with. I honestly believe that if you come out of prison, you need a support group and not a parole officer.

GROSS: So I'm interested in hearing your story about how you went from coming-of-age in prison to then being - you know, getting out, eventually becoming a youth drug counselor - work that you're still doing - and having a movie career. I mean, it's not like you were studying acting (laughter) while you were in prison.

TREJO: (Laughter) Well, you know, it's funny. But when people say where did you study, I always think - standing on the yard in San Quentin, knowing that there's a riot coming, you're absolutely scared to death with every fiber of your body. You know - I might get killed right now. And you have to, like, pretend you're not. You know (laughter), you have to stand there and make everybody think you like it. You know, you can't even sweat. It's like you're standing there. You just got this smirk on your face, like yeah, yeah, we're going to do it now. Oh, yeah. And people around you see that and go, yeah, yeah. And then you just build everybody up. And then all of a sudden, there's no fear. It's all rage. And, you know, 10, 15 people enraged is a really powerful force.

GROSS: So you're saying you did learn how to act in prison.

TREJO: That's - yeah, how to act not afraid (laughter).

GROSS: Right, right. So you didn't need to study the method or Stanislavski or anything to...

TREJO: No. Yeah...

GROSS: ...To find that out.

TREJO: ...I always joke about my acting coach Juan Strasberg (ph).

(LAUGHTER)

TREJO: You know what? You're the only one that's ever laughed at that. When I always say my acting coach Juan Strasberg, people think, oh, is that a (laughter)...

GROSS: Is that a person?

(LAUGHTER)

TREJO: Yeah.

GROSS: So let's take a short break here, and then we'll talk...

TREJO: OK.

GROSS: ...Some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is Danny Trejo - actor, former prisoner and now one of the producers and a witness in a movie called "A Survivors Guide To Prison."

TREJO: "Survivors Guide To Prison."

GROSS: It's a new documentary. We'll be right back after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF BEASTIE BOYS SONG, "TRANSITIONS")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. If you're just joining us, my guest is Danny Trejo - an actor, a drug counselor and somebody who spent his formative years in prison. And on screen, he's played a lot of very, very tough people (laughter), including in movies like "Machete" and "Desperado," and in the TV series "Breaking Bad" and "Sons Of Anarchy"

TREJO: "Spy Kids."

GROSS: "Spy Kids."

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: That's right. So tell us the story of how you were first cast in a movie.

TREJO: OK. The way I got in the movie business - you know, I was running around, trying to be an extra. They used to give you 50 bucks for being an extra. I ran into a good friend of mine, a guy named Eddie Bunker, who was a great writer. And people don't know it. Eddie actually got famous because he could write writs in prison. That's one of the reasons why the department of corrections hated him because you...

GROSS: Oh, W-R-I-T-S. Like...

TREJO: Writs. You know, a writ to get you out of prison...

GROSS: Oh, OK.

TREJO: ...Like a writ of habeas corpus. He would charge people, and he would get their documents. And he'd look at them. And he'd go, hey, wait a minute. Oh, right here. They violated your blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And he would write a writ. Now, a writ has to be grammatically correct. It has to be written in the language of the court. So basically they've stacked the deck against you because nobody knows that stuff but attorneys. But Eddie knew how to do it, so people would pay him. He'd write a writ. You'd come back to court, and he got a lot of people out of prison. And so I've known him for years.

And then when I ran into him on a movie called "Runaway Train," with Jon Voight and Eric Roberts, he asked me if I was still boxing 'cause he had saw me win the lightweight and welterweight title up in San Quentin. And I was lightweight and welterweight title of every institution I was in. That was my uncle teaching me how to box. And so he said, are you still boxing? And I said, Eddie, I'm 40 years old. I don't want to get hit in the face anymore. I train. I'm in shape. And he says, we need somebody to train one of the actors how to box. And I said, what's it pay? And he said 320 a day. And I said, how bad do you want this guy beat up?

GROSS: (Laughter).

TREJO: You know, 'cause I - 320 a day? That was more money I was making a week. You know, I was a drug counselor, right? And he goes, no, you have to be real careful, Danny. Actor's real high-strung. He might sock you. I said, Eddie, for 320 a day, give him a stick. Are you crazy? I've been beat up for free, homes.

GROSS: (Laughter).

TREJO: And I started training Eric Roberts how to box.

GROSS: How did he do?

TREJO: He can't fight.

(LAUGHTER)

TREJO: And then Andrei Konchalovskiy had Eric pick...

GROSS: He was the director of the film.

TREJO: Yeah, Andrei Konchalovskiy was the director - very soft-spoken Russian, beautiful man, beautiful man. I mean, he was like - he wore those funny sweaters with the leather on the - you know, on the elbows...

GROSS: Oh, the elbow patches.

TREJO: ...And cardigan. And it just was real - always had these sweaters on and just soft-spoken. And he didn't understand. Eric was a movie star, OK? Now, movie stars yell and scream and walk to their trailers and stuff, you know what I mean? So Andrei couldn't really understand what was, you know - because like I said, you don't do that in Russia (laughter). And so when he saw Eric was listening to me as far as boxing and stuff, he came over, Andrei comes over and says, you be in movie. You fight Eric. And you be my friend - I'll never forget that - said, and you be my friend. Now, if you have a prison background you don't like people to say, you be my friend. You know, 'cause - he just, yeah, nah (ph), you - you'll be my friend.

GROSS: (Laughter).

TREJO: And so - and then I'll never forget - then he leans over and he kisses me on one cheek, kisses me or the other cheek. And then he walks away. I told Eddie Bunker, Eddie, I'm going to train that kid for 320 a day. But if I'm going to be kissing that old man, I want more money. And I'll never forget, they had somebody cast. And I remember Andrei going, no, no, no, no, no, look. And he went to Eric's face and he goes - ah (ph). And then he went to this other guy they had cast, who looked a little like Antonio Banderas, go - ah (ph). And then he came to me and went, look - (growling).

GROSS: (Laughter).

TREJO: Contrast, contrast - he kept saying, contrast. I didn't know if he was like, making fun of me or not. But he wanted contrast. So I got the job (laughter).

GROSS: So is - do I have this right? Because I read an interview with you in which you said that before you were on the set of "Runaway Train," you were working as a drug counselor. And a teenager who you were working with was on the set and asked you to come with him...

TREJO: Yeah.

GROSS: ...'Cause he was having trouble staying away from drugs and he was worried...

TREJO: Yes, yes.

GROSS: ...He was going to succumb. So you accompanied him to the set, and there they asked you to box...

TREJO: Yeah, absolutely. But I had been working...

GROSS: ...To teach Eric Roberts and you ran into Edward Bunker.

TREJO: Edward - but that's - exactly. I had been working as an extra. And I kind of - this kid was trying to stay clean. And he was a PA - production assistant. And - I don't know what happened to him, but running into Eddie changed my life again.

GROSS: So - to give a sense of some of the small parts you had before becoming better known, I'm going to read some...

TREJO: I was Inmate No. 1, Inmate No. 1.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: I'm going to read some of the...

TREJO: OK.

GROSS: ...Titles of films that you were in. And some of these date back to before "Runaway Train." OK - "Lock Up," "Bulletproof," "Death Wish 4: The Crackdown," "Penitentiary III," "Carnal Crimes," "Doublecrossed," "Whore," "Guns," "Marked For Death," "Maniac Cop 2" (laughter). That...

TREJO: Yeah.

GROSS: ...That just takes us to 1990 (laughter). And your roles include - Prisoner Tattoo Artist - yeah. So that'll give a sense of some of how - some of the roles you were cast in...

TREJO: Yeah. Well, right now, they're doing a documentary on my life right now and it's called "Inmate #1." And the reason is...

GROSS: Oh.

TREJO: ...because I played Inmate No. 1 in just about - the minute I would walk, I'd be Inmate No. 1. I thought I had a great career going, you know? 'Cause I'm making 320 a day. And sometimes, I'd work three or four days. And I can remember the first time I got interviewed, this young lady probably fresh out of interview school, she says - and then she was Latina so she...

GROSS: Is there an interview school?

(LAUGHTER)

TREJO: ...But she is - was Latina so immediately she says, Danny - don't you feel you're being stereotyped? And I says - what are you talking about? She says, well, you know, you always play the mean Chicano dude with tattoos. And I thought about it. I says, I am the mean Chicano dude with tattoos.

(LAUGHTER)

TREJO: What're you - somebody finally got it right. You know, they're not using Marky Wahlberg to (laughter) be the mean Chicano dude.

GROSS: Actor Danny Trejo is a producer of the new documentary "Survivors Guide To Prison," which he also speaks in. After hearing him tell us how he got his first big break from novelist and screenwriter Edward Bunker, who had been Trejo's fellow inmate in San Quentin, we thought it would be great to listen back to an excerpt of our 1993 interview with Bunker. We'll do that after a break. We'll also hear more from Trejo. And David Edelstein will review the new film comedy "The Death Of Stalin." I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF CHARLIE HUNTER'S "CIELITO LINDO")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with actor Danny Trejo, who's known for his menacing roles in movies like "Machete" and TV shows like "Breaking Bad." He spent over 10 years in prison before starting his acting career. Now he's a producer of the documentary "Survivors Guide To Prison." He also speaks in the film.

So I want to ask you about your role in "Breaking Bad" and...

TREJO: That was fun.

GROSS: ...And you play Tortuga - which also means - in...

TREJO: Turtle.

GROSS: ...in Spanish, that means turtle. So you're an informant for the DEA. And in this scene, you're meeting with DEA agent Hank Schrader, who's played by Dean Norris. He's going to you for information. But you're taking your time. You're really toying with him.

TREJO: Yeah.

GROSS: And so...

TREJO: I had one of those books from the airlines. Oh, yeah...

GROSS: This - SkyMall. SkyMall.

TREJO: ...Yeah, I want to order two of these. Yeah.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: It's the catalog that you can order from while you're in the plane.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So, you're taking your sweet time. You're trying to show that like - you're the one in control here, not the DEA agents. So Hank is sitting there with his fellow DEA agents while you're toying with them. And you say to one of them, hey, give me that SkyMall on the table over there. And then you start, like, ordering things from SkyMall and giving out, like, the catalog number for each item. So this is the scene. You speak first.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "BREAKING BAD")

TREJO: (As Tortuga) Hey, white boy, better learn Espanol. This ain't Branson, Mo. Know what I'm talking about? You know what? I'll teach you. (Speaking Spanish). It means, let's make a deal.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) So go ahead. We're waiting.

TREJO: (As Tortuga) OK, right here, item SS4G - Yankee stadium final season commemorative baseball hand-signed by Derek Jeter. Blanco, white this down. Oh, man, watch out - 66100ZBG - large-sized floor runner. Look at that. It's a rug you put on the floor, except for it looks like a hundred-dollar bill. I love them. Get me 20 of them. I'm going to put them all over my casa.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) We'll get you three.

TREJO: (As Tortuga) You'll get me 10.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) Five.

TREJO: (As Tortuga) Taxes.

DEAN NORRIS: (As Hank Schrader) How about you stop [expletive] us off here? Where's the meet? When's it going down?

TREJO: (As Tortuga) White boy don't like "Let's Make A Deal."

NORRIS: (As Hank Schrader) White boy's going to kick your ass if you don't stop wasting his time.

TREJO: (As Tortuga) Hey, white boy. My name's Tortuga. You know what that means?

NORRIS: (As Hank Schrader) If I have to guess, I'd say that's Spanish for [expletive].

TREJO: (As Tortuga) Tortuga means turtle. That's me. I take my time, but I always win.

GROSS: OK. So finally, you make the deal. You give the agents the information they're looking for.

TREJO: And the Emmy goes to Danny Trejo for Tortuga.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: And so the agents are - you've tipped them off to when there's going to be a deal going down, a drug deal going down. They're in the desert waiting for this drug deal to go down. And what you see is this turtle walking towards them - this big, large tortoise - with your decapitated head on it because your boss knows that you informed.

TREJO: Yeah.

GROSS: And so Dean Norris is kind of sickened by the scene. And he goes to his car because, you know, I think he's about to throw up.

TREJO: Yeah.

GROSS: And - but all the other agents are kind of watching your head on this turtle and they're kind of like laughing and making fun of it, not realizing that the turtle is also carrying a bomb. It detonates, and all the other agents are blown up.

TREJO: Right.

GROSS: What was it like for you to see this facsimile, this model of your head as if it were decapitated, riding on top of this turtle - mounted on top of this turtle?

TREJO: I thought it was funny. I mean, like, it was kind of creepy because they did such a great job with the head. But, you know, it's just like kind of like wow, nobody's ever done this in Hollywood.

GROSS: (Laughter).

TREJO: And my agent, Gloria (ph), says, Danny, do you want to do one of Hollywood's firsts? And I said, what? She says, well, you're going to go across the desert on a turtle. And I thought, animation? That's a big turtle. And she goes, well, just your head. And I said, has anybody else done it? They said, no. Has Sly done it? No. Has Schwarzenegger done it? No. OK, then I'll do it.

GROSS: So before we go...

TREJO: I'm not going. Where are you going?

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: What's the role in which you are most cast against type? Because your type is always kind of like tough and menacing, like the most powerful person. So have you played like - God, he's so vulnerable? He's, you know...

(LAUGHTER)

TREJO: You know what? I did a roll called "Sherrybaby" where I was like a nice guy with Maggie Gyllenhaal.

GROSS: I saw that. I remember very little about it, but I saw that.

TREJO: I was - yeah. It was kind of a real - she was like abused and abused and got out of prison. It kind of showed what happens when a woman gets out of prison and how she's used and abused. And I was like her buddy or her good friend or whatever. You know what I mean? And she was wonderful, great actress. But we went all over the world. People love that movie. And then I got to say, I did a movie called "Storks" where (laughter) - where I played a heroic stork, you know, who lost his baby.

GROSS: Oh, was this animated?

TREJO: Yeah. And I guess that was against my type. I don't know.

GROSS: Well, it's been a pleasure to talk with you. Thank you so much.

TREJO: Thank you. It's been wonderful. Thank you so much.

GROSS: Danny Trejo is a producer of the new documentary "Survivor's Guide To Prison," which he also speaks in. It's available on iTunes and Amazon. Earlier in the interview, he described how he got his first big break from Edward Bunker, who had been a fellow inmate in San Quentin and went on to write novels and screenplays. We'll hear an excerpt of my 1993 interview with Bunker after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF SIDESTEPPER'S "ME VOY ANDANDO REMIX")

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. Now we're going to hear an interview from our archive with Edward Bunker, the writer Danny Trejo first met while they were both prisoners in San Quentin. Bunker, who died in 2005 at the age of 71, grew up in Southern California foster homes. At the age of 17, he became the youngest inmate in San Quentin after having stabbed a guard at a youth detention facility. He spent 18 years in some of the nation's toughest prisons for robbery, forgery and selling drugs.

While doing time in San Quentin, he published his first novel, "No Beast So Fierce," about an ex-con who can't get legit work and returns to crime. The novel was adapted into the 1978 film "Straight Time," which starred Dustin Hoffman. Bunker co-wrote the screenplay for the 2005 film "Runaway Train." While that was being shot, Bunker and Trejo met again on the set. And Bunker helped give Trejo his first big break, hiring him to train actor Eric Roberts for the boxing scenes in the film.

Bunker wrote several novels about crime and prison life and in 2000 published a memoir called "Education Of A Felon." In Quentin Tarantino's 1992 crime film "Reservoir Dogs," Bunker played Mr. Blue. When we spoke in 1993, Bunker read an excerpt from his first novel, "No Beast So Fierce."

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

EDWARD BUNKER: (Reading) I sat on the littlest toilet at the rear of the cell, shining the hideous bulb-toed shoes that were issued to those being released. Through my mind ran an exultant chant - I'll be a free man in the morning. But for all the exultation, the joy of leaving after eight calendars in prison was not unalloyed. My goal in buffing the Adley shoes was not so much to improve their appearance as to relieve tension. I was more nervous in facing release on parole than I had been on entering so long ago.

(Reading) It helped slightly to know that such apprehensiveness was common, though often denied, by men to whom the world outside was increasingly vague as the years passed away. Enough years in prison and a man would be as ill-equipped to handle the demands of freedom as a Trappist monk thrown into the maelstrom of New York City. At least the monk would have his faith to sustain him, while a former prisoner would possess memory of previous failure - of prison and the incandescent awareness of being a ex-convict, a social outcast.

GROSS: Thank you for reading that. Edward Bunker, do you know that on the author bio on the press release that accompanies the republication of "No Beast So Fierce," it says, Edward Bunker has not been arrested in over 20 years. That's an unusual thing to find on an author bio. Did you want that mentioned on there?

BUNKER: Yeah, sure, I wanted that mentioned - yeah - because, you know, people have the image of the prison - the convict writer Jack Abbott kind of ruined things. And Smith and other people who, you know, have written - people - Buckley went to bat for Smith and Maler for Abbott and, you know, and they got in trouble quick, you know - committed rapes, murders, robberies, you know, somebody that's really been rehabilitated. So yeah, I like the idea that I haven't been arrested for 20 years. That kind of changes things, you know. I mean, don't you think it's salient?

GROSS: Absolutely. You wrote this book while you were in prison?

BUNKER: Yeah.

GROSS: Were you encouraged to write while you were in prison?

BUNKER: When I was real young, I was encouraged to write. There was an old silent film star that used to write me from - correspond with me and sent me magazines and subscriptions to The New York Times. And she encouraged me to write. And I'd read the, you know, I read a lot. And I'd read that - I know that Cervantes wrote part of "Don Quixote" in prison and that Voltaire was in prison. And actually, if you go all the way back to Socrates, you know, that was the first prison writer. And there's been Genet. And so, you know, there's a lot of examples of people who've used time in prison to write books.

GROSS: You were aware of that while you were writing in prison?

BUNKER: I wasn't aware of that when I first started. I don't - all of that much. The first thing that I had was Chessman. And I was up in the hole, which was behind - right behind death row when Caryl Chessman was up there. And I used to talk to him through the ventilators. And I was 18 or 19. And a sergeant brought an Argosy magazine around from death row. And they had excerpted the first chapter of Chessman's book, "Cell 2455, Death Row." That was a chapter about an execution. And it was unbelievable to me that a convict in prison - on death row or just in prison - could get published. And Argosy magazine could accomplish that and mentioned that the book was going to be published. And when it was published, it was a smash best-seller internationally. So that's really what started me writing.

GROSS: How did you get agent when you were in prison?

BUNKER: I wrote this agent and told him that, you know, I was here in prison and I aspired to write. And they had done an issue in Esquire magazine about writer - the New York literary world. And they had a chart of, you know, how they do in magazines and these agents and that agent. And this was an Ayn Rand's agent - originally had been Ayn Rand's agent and was the real old agency in New York, one of the first ones.

So I wrote them and explained my situation and if they'd be interested in reading my stuff. So I sent it to them. And they said, we can't sell this. If you do anything else, send it to us. So every time I'd write one of those novels, every two or three years, I'd send them and they'd say no. And finally, on the sixth one, he said, I think I can sell this.

GROSS: You wrote six novels before the one was published?

BUNKER: Right. I wrote for 17 years before I got published.

GROSS: Did you show it to any of your fellow prisoners?

BUNKER: Oh, yeah. I was - I used to - yeah, I had, you know, yeah, I used to write dirty stories that I'd rent for sale in the joint. That's where I made my cigarettes, you know, and coffee. And I'd write reports. I always had - after a while, after a couple of years, I had a very, you know, powerful clerical positions in the state prison. And I was like, you know, associate warden's clerk because I could write so well. And, you know, those reports that go to Sacramento and the district attorney's office and things like that that I, you know, so I did a lot of that writing, you know, report writing. And I would write letters for guys. And then I got into law. I studied law. I worked as a law librarian for three or four years.

GROSS: What - your novel is about an unrepentant criminal. I imagine that that didn't really help your reputation among prison authorities.

BUNKER: No. In fact, I once wrote an essay on how to commit an armed robbery, a primer on planning and commissioning a successful armed robbery. They found it in my cell. They didn't - they really didn't like that. But I don't think they paid any attention to this book. I don't think they read very much, the prison authorities.

GROSS: The novel, "No Beast So Fierce," was first published in 1973. I believe you were paroled that year also?

BUNKER: Yeah.

GROSS: Was that before or after the publication?

BUNKER: No, I was in when it was published.

GROSS: And when were you paroled?

BUNKER: I was paroled later on, about a year and a half later.

GROSS: What was it like for you that time when you got out of prison? You know, you had a novel. You could have gone to a bookstore and bought, you know, looked at your book there.

BUNKER: It was very different. I left in a limousine. They sent a limousine for me. And we were going to make a movie. I was in preproduction on making "Straight Time." And so they sent a limousine for me. And that was a far different situation. Of course, they could take me around the block and dumped me out. I didn't care after I got away, you know. But yeah, my relationship with the world changed.

GROSS: Was that the last time you were in prison?

BUNKER: Yeah and the last time I was arrested.

GROSS: In the introduction to your book, you thank Dustin Hoffman for carrying you for six months. You're referring to the time you worked with him?

BUNKER: Oh, another book. That's in...

GROSS: Oh, I'm sorry. That's in your other book. That's right.

BUNKER: ...In the dedication of "Little Boy Blue." Yeah, he did. I mean, they hired me when I got out. They hired me as a technical consultant and, you know, and paid me all the way through preproduction and production, gave me - I did an acting job. I played a role in the movie, got a SAG card. And so it changed my life. I mean, it didn't change me, but it changed my relationship with the world.

You know, I think I've changed. I've changed kind of over time by virtue of the family. I've been with the same woman for 15 years. So I changed slowly. But when I got out, I didn't have any different attitude than I'd always had. But my relationship with society changed. I've been on the cover of Harper's Magazine. I had a book published. I had another one in production. I had a movie being made. That's a whole lot a different situation than getting out, you know, with $40 in your pocket.

GROSS: Tell me about one of the days when you got out with $40 in your pocket.

BUNKER: Well, I got out one time with 40. I had - and they'd given me the dress-out shoes. I was trying to get a job. And I remember this very clearly in Los Angeles, one of those hot LA days, you know, that really gets smoking - 100 degrees. And I was walking around. And I had blisters from these shoes, these new cheap shoes that they'd given me, these dress-out shoes. And I'm walking from job application to job application trying to get a job. And it was so bad that I had blisters on my blisters and no money, you know, and a little furnished room. And the rent's running out. And the parole officer's on my case. Yeah.

GROSS: You were on the FBI's 10 Most Wanted list for a while?

BUNKER: Once upon a time - yeah.

GROSS: What got you on there?

BUNKER: It was really some forgeries. Those were the - for the - was the charge.

GROSS: Were you proud in a way? Did you feel like you'd made it to the top?

BUNKER: Well, yeah, it's kind of a, you know - I wouldn't say proud. But it scared me, I know that - but - because it puts a lot more heat on you. They usually put you - they used to only put you on the 10 Most Wanted when they knew they were going to arrest you the next day.

GROSS: (Laughter) To look impressive?

BUNKER: To look impressive - that's true, you know?

GROSS: Did anybody recognize you from your 10 Most Wanted FBI photo that appeared in post offices?

BUNKER: No, but I was afraid that they would. I didn't know it. And I was in Florida. I was in Miami. And I went into a post office. And I saw my - you know, my picture there. It scared me to death. And that's really the reason I didn't go, you know?

GROSS: Did you run out of the post office?

BUNKER: No. I didn't quite, but I left quickly. You know what I mean? I don't think I quite ran. But it was - I got out of there.

GROSS: Was it a good photo?

BUNKER: No. It was a bad photo. But still, who knows, you know? You'd be surprised how many people, you know, recognize you.

GROSS: Right. So it's been 20 years since you were in prison. What have you been doing for the past 20 years? How have you earned a living? What's your day-to-day life like?

BUNKER: I live the life of a writer. I do all right. My books do fairly well. I get some movie-writing work, rewriting work. I get a little acting work here and there. I live a very kind of - very quiet life. It's pretty good. I have a great life, actually. You know, I sleep. I get up. I go to eat breakfast. I clean the house. And I write. I write seven days a week. And I have good friends. I have a good wife.

GROSS: I want to thank you very much for talking with us.

BUNKER: Yes, dear.

GROSS: Edward Bunker recorded in 1993. He died in 2005 at the age of 71.

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. Armando Iannucci, who created the award-winning TV show "Veep," has made a satirical comedy about Joseph Stalin called "The Death Of Stalin." The film features British and American actors and is set at the time of Stalin's death amid the frenzy and power struggles that followed. Steve Buscemi stars as Nikita Khrushchev. Film critic David Edelstein has this review.

DAVID EDELSTEIN, BYLINE: Armando Iannucci's "The Death Of Stalin" is an acid satire of the days in 1953 when the Soviet Union lost its totalitarian leader of three decades, and members of his inner circle argued, plotted and killed a lot of people while selecting a successor.

Don't expect much Russian flavor, though. The joke is that the characters order torture and mass murder in the accents of Cockney or American bureaucrats. They're prissy, pissy, peevish, potty-mouthed. Why is that a joke - because of the colossal disconnection between small-minded egotistical clowns and the large amount of horror they inflict thanks to their vast and unchecked power. The movie isn't funny haha like Iannucci's HBO series "Veep" or his British series "The Thick of It," which he turned into the gorgeously profane feature "In The Loop." This is "In The Loop" through the lens of George Orwell's "Animal Farm" or "1984." It's funny - oh, my God.

If the movie has a single theme, it's the disfiguring effects of terror on the simplest human interactions. Any statement, however trivial, can get you hauled off and shot. Before Stalin keels over from a stroke, the fear of his displeasure produces a kind of verbal slapstick in which his subordinates stammer and cast furtive glances at their leader and one another for clues to their status. Did Stalin laugh? Did Stalin frown?

It makes psychological and poetic sense that Stalin lies for 12 hours on his bedroom floor in soiled clothes because his men are too frightened to make a decision about what to do next. Plus, Moscow's competent doctors are either dead or in the Gulag. The bulk of "The Death Of Stalin" depicts the struggle for party chairmanship between Nikita Khrushchev, who most of us have heard of, and Lavrenti Beria, whom most of us haven't. Khrushchev is no saint but is played by a gray sputtering Steve Buscemi. He's rather lovable. He's St. Francis of Assisi next to Simon Russell Beale's bullying, thick-necked Beria who tortures prisoners with relish and sexually preys on young girls.

If you didn't know Khrushchev succeeded Stalin, you'd put the odds on Beria, who's more Machiavellian and ruthless and who has the ear of the weak-willed acting premier Malenkov played by Jeffrey Tambor. Beria does a brilliant job ensuring Khrushchev won't be doing any master planning by nominating him to micromanage Stalin's funeral.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "THE DEATH OF STALIN")

SIMON RUSSELL BEALE: (As Lavrenti Beria) We need someone to take charge of the funeral.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character) What about Comrade Khrushchev?

STEVE BUSCEMI: (As Nikita Khrushchev) Where is this coming from?

BEALE: (As Lavrenti Beria) I formally propose Comrade Khrushchev be given the honor of organizing the funeral.

BUSCEMI: (As Nikita Khrushchev) Come on. I don't have any time to do that.

BEALE: (As Lavrenti Beria) Well, if I can do three things at once, you can at least do two.

BUSCEMI: (As Nikita Khrushchev) What the hell do I know about funerals?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character) You said you wanted to honor his legacy. You told me last night in the bathroom.

BEALE: (As Lavrenti Beria) All those in favor.

JEFFREY TAMBOR: (As Georgy Malenkov) All those in favor.

BUSCEMI: (As Nikita Khrushchev) No.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character) Well, I think you'd be good, actually, you know.

BEALE: (As Lavrenti Beria) Passed unanimously.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character) Niki Khrushchev, funeral director. It suits you.

EDELSTEIN: Armando Iannucci has a genius for depicting the formality of statecraft side-by-side with the chaos of personality, fertile territory for a cast of brilliant forces from both sides of the Atlantic. Jeffrey Tambor's Malenkov is both glum and jumpy, feebly asserting authority while pitiably aware he's in over his head. He can't master the higher math of a system in which the same principle can be twisted to get you both celebrated or executed.

Michael Palin plays the foreign minister, Molotov of cocktail fame, with a grandfatherly gentleness that's in context very creepy. Plus, he carries echoes of the Orwellian black comedy "Brazil." Andrea Riseborough is Stalin's giddy daughter, whose life of privilege has made her weirdly oblivious to the realities of Soviet life. Paddy Considine kicks off the movie as a symphony orchestra manager whose continued existence rests on his ability to deliver to Stalin the tape of a concerto that was, alas, broadcast live unrecorded.

It's the casualness of the horror that makes you cry out in disbelief. When Beria decides to win the Soviet people's favor by halting executions, it takes time for his order to trickle down, during which an officer in the midst of putting bullets into people's heads takes huffy umbrage when a messenger tries to interrupt him and waves him off to get one more victim in. The message to stop is delivered, whereupon the next man in line - spared - gazes blankly at his neighbor's body, barely able to process the half-second difference between life and death. In such small strokes, "The Death Of Stalin" transforms farce into tragedy.

GROSS: David Edelstein is film critic for New York Magazine. Tomorrow on FRESH AIR, we'll talk about artificial intelligence, driverless cars, robotics, virtual reality and other emerging high tech. What are some of the new breakthroughs, like using computers to read scans and identify signs of lung cancer, and what can go wrong? My guest will be Cade Metz, who covers high tech for The New York Times and looks at where these technologies are taking us for better or worse. I hope you'll join us.

(SOUNDBITE OF DAVE DOUGLAS' "PLAY IT MOMMA")

GROSS: FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our technical director and engineer is Audrey Bentham. Our associate producer for digital media is Molly Seavy-Nesper. Roberta Shorrock directs the show. I'm Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF DAVE DOUGLAS' "PLAY IT MOMMA")

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.