Journalist Robert Sullivan.

Journalist Robert Sullivan. His first book, “The Meadowlands” (now in paperback) an urban adventure in the wilds of the marshy dumping area between New Jersey and New York was praised for its wit, imagination and intelligence. His new book “A Whale Hunt” (Scribner) chronicles the two years he spent watching the Makah Indian tribe in Washington state as they prepared for and attempted their first whale hunt in over 70 years. But they didn’t do it alone: they were surrounded by angry protestors and hounded by the press.

Other segments from the episode on October 23, 2000

Transcript

DATE October 23, 2000 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

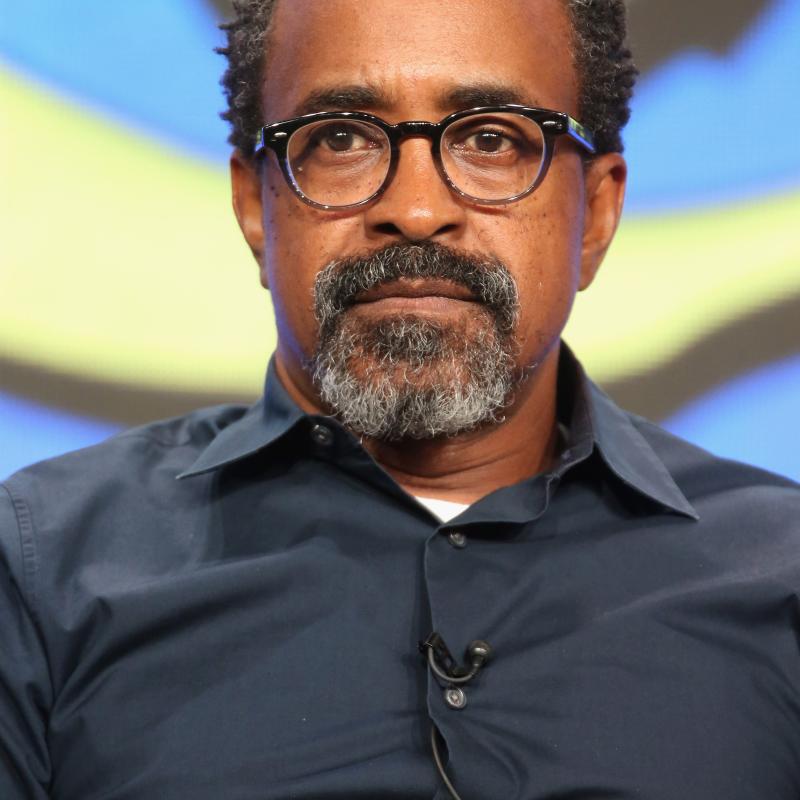

Interview: Tim Meadows talks about his career on "Saturday Night

Live" and his new movie, "The Ladies Man"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

(Soundbite of "Saturday Night Live")

Mr. TIM MEADOWS (As Leon Phelps): What's happenin'? And welcome to "The

Ladies Man," the love line with all the right responses to your romantic

queries. My name is Leon Phelps and to those of you that are uninitiated, I

am an expert in the ways of love. Now I'm doing good, if you are askin'. I

got my Courvoisier cognac right here. And I'm ready to take your calls. So

if you have a romantic query and you are under the age of 50 and you're not

freaky or disgusting, please give us a call.

GROSS: Leon Phelps is back on the air, giving more bad advice in the new

film

"The Ladies Man." Tim Meadows co-wrote and stars in the film. He

originated

the character of The Ladies Man on Saturday Night Live. He was a cast

member

of the show from 1992 till the end of last season. Some of the characters

he

became best known for are the gangster-rapper G. Dog(ph), Lionel Osborne,

the

host of the public service TV show "Perspectives," and the host of the radio

show "The Quiet Storm." He also did impersonations of O.J. Simpson, Johnnie

Cochran, Ike Turner, Don King and Michael Jackson. This season, Meadows

will

co-star in "The Michael Richards Show," which premiers tomorrow.

I asked Tim Meadows about the origins of The Ladies Man character.

Mr. MEADOWS: Well, I kind of started doing it in Chicago. I used to call

radio stations and talk shows and I would disguise my voice because I didn't

want to be recognized because I was on "Saturday Night Live." And I would

do

this for the entertainment of my wife in our living room. And so I would

call

and, you know, if they were talking about, you know, the economy or

something,

I would ask a question like--that made sense so that the person had to

answer

it and they had to deal with this guy on the phone. And I would do, like,

you

know, `Listen--hi. This is Brother Gurr(ph) from Chicago. And I was

wondering how is it possible that there could be, you know, poor people and

rich people living in the same neighborhood in this--you know, in this

country? It's--I find it very uncomfortable. I'm gonna hang up and let you

answer the question now.'

GROSS: So how did you come up with this voice before you had the character

of

The Love Man?

Mr. MEADOWS: It sort of, like, evolved. It was--I don't know, it took--it

was years because I used to do a tough rapper who lisped on "Saturday Night

Live." And it was called G. Dog. And he basically talked straight, you

know, but he was tough. And then I sort of like started to just change it

as

I started doing, you know, these phone calls. And I sort of like, you know,

based the characteristics that Leon has on guys that I'd met in Detroit when

I

was growing up, when I was a teen-ager. I worked at a liquor store and

there

were these guys that would come into the store and they would buy

Courvoisier

on the weekends for their big date. And, yeah, I don't know. I couldn't--I

never--I didn't date. I didn't have a lot of women, you know, liking me.

So

they amazed me because they were--they had a lot of girlfriends and they

were--had their own style and they were very independent and very cool.

And,

you know, me and my friends sort of looked up to them.

GROSS: One of the great things about The Ladies Man is that the advice he

gives is so wrong most of the time.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah.

GROSS: Can you think of some great, wrong advice that Leon gives?

Mr. MEADOWS: Well, he--you know, he says that, you know, if you're a lonely

lady and you're living in the city that, you know, `I would suggest that you

hang out at a bus station with no underpants on because that will attract

men

to you. I know it would attract me to you.' And, you know, I think his

suggestions to women, you know, in general is like--is to be easy, you know,

which is not really good advice.

GROSS: So how did you come up with this advice? Is this advice that--is

this

stuff you've heard guys talking about over the years?

Mr. MEADOWS: It's sort of just--I'm--I just...

GROSS: I'm a woman and I want to know.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah. Well, I think of the worst advice possible, and I think

that's what Leon sort of gives, you know. It doesn't work in the real world

'cause, you know, things have changed since the '70s.

GROSS: There's a scene in "The Ladies Man" movie where--well, there's a

group

of white men whose wives have cheated on them with Leon, The Ladies Man,

and...

Mr. MEADOWS: And black men.

GROSS: And black men. OK, yeah.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah.

GROSS: And this group is led by a character played by Will Ferrell of

"Saturday Night Live."

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah.

GROSS: And there's a scene where he's trying to incite them to take action.

And he says, `We can't let The Ladies Man take away our masculinity. We're

men.' And then they break out into a Broadway-style song-and-dance number,

singing `the time has come to kill The Ladies Man.' And it's a very funny

scene. Although you mock this kind of Broadway song-and-dance number, I'm

wondering if there's a period in your early performing career when you

really

hoped to get on Broadway and be in musicals.

Mr. MEADOWS: Me, personally?

GROSS: Yeah, you personally.

Mr. MEADOWS: No.

GROSS: No.

Mr. MEADOWS: No, I've--you know, I can sort of sing and stuff, but, I mean,

I'm not a fan of, you know, Broadway musicals. I know a lot of people like

them and I understand. I can't watch them without laughing because, you

know,

to see--to me, the funniest thing in the world is to see people breaking

into

song 'cause it doesn't happen in real life. And it just seems so fake and

so--I don't know, I just--I've never been a fan of it. And I think that's

one

of the reasons I really like that scene, too, is because it's sort of making

fun of that stuff.

GROSS: Affectionately, I thought.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah, I don't think it's affectionately.

GROSS: OK.

Mr. MEADOWS: I think it's pretty mean-spirited.

GROSS: OK.

Mr. MEADOWS: We're not nice guys. You have to understand that about us.

GROSS: It was funny. Billy Dee Williams has a part in this. He plays, I

think, the owner as well as the bartender at, like...

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...you know, the neighborhood bar where Leon hangs out.

Mr. MEADOWS: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And it's a pretty cheapo kind of place.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah.

GROSS: But he's the suavest guy in the movie, for real. You've played a

character on "Saturday Night Live" that reminded me--I think it was supposed

to be like Billy Dee Williams. He's doing, like, a Colt 45-type commercial.

Mr. MEADOWS: Oh, yeah. It was for...

GROSS: Cold Cock beer.

Mr. MEADOWS: It was called Cold Cock, yeah.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. MEADOWS: And it was a beer that if you take a sip of it--and it's so

strong that it would--you, literally, would get knocked out. And a big fist

comes out of the can and punches you.

GROSS: Why don't we hear a little bit of that?

(Soundbite of "Saturday Night Live")

MEADOWS: You know, when I entertain at home, occasionally, my friends and I

like to discuss just what is the best malt liquor.

Unidentified Actress #1: I say Bull.

Unidentified Actress #2: I say Cobra.

MEADOWS: And I say it's all just talk, unless it's the one they call Cold

Cock.

Unidentified Singers: (In unison) Cold Cock.

Unidentified Actor #1: There's only one malt liquor that'll get your head

hummin'.

MEADOWS: Cold Cock's the one you'll never see comin'.

Unidentified Singers: (In unison) Cold Cock.

(Soundbite of fist punch)

MEADOWS: Drop it.

Unidentified Singers: (In unison) Cold Cock.

MEADOWS: I have yet to meet the man that can finish a whole Cold Cock can.

Unidentified Actress #3: I ain't afraid of no can of beer. Gimme one.

Unidentified Singers: (In unison) Cold Cock.

Unidentified Actress #3: Mmm, Cold Cock.

(Soundbite of fist punch)

Unidentified Actress #3: Whew! You one more liquor picker.

Unidentified Singers: (In unison) Cold Cock.

MEADOWS: Like I said, it's all just talk unless it's the one they call Cold

Cock.

Unidentified Singers: (In unison) Cold Cock.

(Soundbite of fist punch)

MEADOWS: Fantastic.

Unidentified Announcer: Cold Cock, you never see it coming.

MEADOWS: Damn. That's one strong malt liquor.

Unidentified Singers: (In unison) Cold Cock.

GROSS: Well, you know, I'm wondering what Billy Dee Williams thought of

playing a part in your movie, knowing that you had done this satire of him

on

"Saturday Night Live."

Mr. MEADOWS: Well, he didn't know that when he signed on to do the movie.

And he found out about it a couple of weeks in the shooting. And so he

didn't--he just said, `Well, my nephew told me that you do an impression of

me. I'd like to hear it.' And I was, like, `No, it's not you, Billy. It's

just a--you know, it's an amalgamation of a bunch of different dudes.' But

I

never did it for him, so I hope he--you know, I hope he never sees it,

actually, because I want to stay friends with him.

GROSS: My guest is Tim Meadows. He co-wrote and stars in the new film "The

Ladies Man." More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Tim Meadows. His new movie, "The Ladies Man," is based

on

a character he created for "Saturday Night Live."

Mr. MEADOWS: OK.

GROSS: One of my favorites is Lionel Osborne. Maybe this is because I work

in broadcasting, but...

Mr. MEADOWS: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...why don't you describe Lionel Osborne?

Mr. MEADOWS: Well, Lionel Osborne was created by Al Franken, the great

writer, and Dave Mandel, another great writer. And they just--they

explained

to me what the joke of the scene was. And Lionel Osborne is--he has his own

daily--or weekly talk show. And it's sort of one of those shows that--where

the network is fulfilling their requirement--FCC requirement. And, you

know,

you sort of have to give these shows to, like, minorities or whatever. And

so

Lionel has had this show forever, and he doesn't really care about the show,

but he has a half an hour to fill every week. So he just sort of talks, and

he doesn't really listen to what the other person is saying. And

ever--he--and that's pretty much it. But he's pretty bored with his job.

GROSS: He's basically clueless.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah.

GROSS: There was--once when Damon Williams played your guest on the show...

Mr. MEADOWS: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...and he was organizing this kind of radical demonstration. And he

said, `There's gonna be blood running in the streets.'

Mr. MEADOWS: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And then your character says, `And what time is that demonstration

scheduled for?'

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah. `What time will the blood be running in the streets?'

`It'll be at about, you know, 4:00 in the afternoon.' `Fantastic, it's 4:30

in the AM and you're listening to "Perspectives." This is Lionel Osborne,

and

I'm talking to so-and-so, and the blood will be running in the streets at

about 4:00 PM.' Yeah, and he's...

GROSS: I consider--I've seen this show. Yeah, go ahead.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah. I mean, he would just--and he'd--the other thing he

would do is repeat the information that you just told him. So if you said,

`Yeah, you know, we're gonna have a rally at 5:00 and, you know, we hope

everybody can make it,' he would just go, `That's great. So there's gonna

be

a rally at 5:00 and this guy hopes that everybody's gonna make it. Now I

understand that there's gonna be a rally.' `Yeah, it's gonna be...' `And

what time is that rally?' `5:00.' `Fantastic. Well, there's gonna be a

rally at 5:00.' You know, I mean, he just sort of repeated the answers over

and over.

And it was the most fun for me to do that character because it's--you know,

Franken used to tell me, like, it's reminiscent of Bob and Ray, you know.

And

it's sort of slow comedy. It's sort of--it's very subtle. And the thing

that

I really loved performing that sketch was because the audience had to sit

there and listen. And you have to sort of play the silences in the sketch.

And it's not a sketch that, you know, starts out of the box being really

funny, but it grows as you start to get the joke of it. And that was what I

really loved about Bob and Ray--was, you know, you sort of had to--you know,

you had to do some work with those sketches, you know.

GROSS: Now in one of your Lionel Osborne sketches, Chris Rock played the

guest.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah.

GROSS: And during the sketch you just started breaking up with laughter.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah.

GROSS: Let me play an excerpt of that.

(Soundbite of "Saturday Night Live")

Mr. MEADOWS (As Lionel Osborne): Now are you a father, Abdul?

CHRIS ROCK (As Abdul): Yes, I have three boys.

Mr. MEADOWS (As Lionel Osborne): And are they involved in the brotherhood?

Mr. ROCK (As Abdul): No, my son, Kareem Jr., currently lives in another

state, I believe. And my other boy--Andre's mother won't talk to me, so

I've

lost track of him. And my other son, Trey, is dead.

Mr. MEADOWS (As Lionel Osborne): That's terrific. If you're just joining

us, it's 4:51 in the AM and you're watching "Perspectives." I'm Lionel

Osborne, and with me is community activist Abdul Kareem Gage(ph), founder of

the Brotherhood for Responsible Brothers Who Are Fathers. They're

celebrating

their first anniversary this week, and all are welcome. And his son is

dead.

Now--don't make me laugh anymore, all right? Now you were--now you said you

were at the Million Man March.

Mr. ROCK (As Abdul): Yes, Lionel.

Mr. MEADOWS (As Lionel Osborne): And how many--how many people were there?

Mr. ROCK (As Abdul): A million, you dumb (censored).

GROSS: Tim Meadows, what went through your mind when you started laughing

live on "Saturday Night Live" during this sketch?

Mr. MEADOWS: Well, I could see in Rock's eyes that he was understanding the

humor of the sketch and that he was--he understood the fact that he was one

of

these new guys who--he was becoming involved in the Million Man March, but

yet

all of his kids hated him. And I could see in Rock's eyes that he was

getting

the joke 'cause the audience started laughing. And then he realized that he

had to say that his other son--one of his sons were--was dead. And I could

just--we were looking at each other, and then I saw a tear coming down

his--out of his eye and then that made me laugh. And we could hear the

band--the "Saturday Night Live" band laughing behind us because, like I

said,

Lionel Osborne is one of those sketches where the audience might not laugh

in

the beginning, so it's quiet. And the band--SNL band was cracking up at

everything we were doing. And Chris and I could hear it. And we just

started

laughing and it was so funny. It was so funny.

GROSS: Did you try to stop from laughing?

Mr. MEADOWS: Yes, which is a big mistake 'cause it's just like being in

church or at a funeral or something, you know, when you're not supposed to

laugh is when it's just multiplied, how funny it is. And I was trying not

to

laugh. And I was trying to go on with it, and then I knew I had another

stupid joke or a stupid question coming up.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MEADOWS: You know, and we just lost it. It was so much fun.

GROSS: Tim Meadows is my guest, and one of the characters he created for

"Saturday Night Live," The Ladies Man, has been spun off into a new movie

that

Tim Meadows co-wrote and stars in.

You grew up in Detroit.

Mr. MEADOWS: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: Tell us a little bit about the neighborhood you grew up in; what

your

family was like when you were young.

Mr. MEADOWS: Mm-hmm. Well, we moved a few times. My parents split up when

I was about six or seven. And when they were together, we lived in a pretty

nice, middle-class neighborhood in Highland Park, Michigan. And then after

they separated, you know, it--my mother was raising us on her own, so it got

a

little harder. And, you know, we were on welfare and we sort of--the

neighborhood was still a nice neighborhood that we moved into, but we were,

like, the poor family in a nice neighborhood. So it came with its own

problems.

GROSS: What were some of those problems?

Mr. MEADOWS: Well, you know, not feeling as though I fit in. You know,

sort

of having to prove myself in school and sports and, you know, socially.

And,

you know, it just always--it just always felt like there was, like, this

struggle to sort of fit in with people and be accepted.

GROSS: When you were, say, in high school, did you think that you would

actually go into comedy?

Mr. MEADOWS: No, I thought that I was going to be a musician at first, when

I was in high school, because I played the sax and so I could play different

woodwind instruments. But I heard Charlie Parker one time on an album and I

sort of slowly packed away my saxophone and never picked it up again.

GROSS: Yeah, I think that happened to a lot of saxophonists.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yeah, they should warn you to never listen to Charlie Parker

if

you just--if you really want to become a professional because you will never

be that good and I knew it. As soon as I heard it, I was just like, `Oh, my

God, this is somebody--I can never be this good and I don't have the

patience

to even practice scales, you know. So there's no way I'm gonna get any

further than, you know, playing for some third-level, funk band in Detroit.'

GROSS: So when the idea of being a musician got put aside, what happened

next?

Mr. MEADOWS: I started college and I was thinking about--I was sort of

reading--I was sort of studying mass communications and journalism and

philosophy a little bit. And then I thought I would, maybe, become a lawyer

and maybe try to go to law school or something. And then I found out about

this improv group in Detroit that were--they were teaching classes--this

teacher. And so I took classes and just really--it was like somebody opened

this new door to myself and just--I learned that I could do these things

that

I had never really done before.

GROSS: You moved to Chicago and worked with Second City for a while.

Mr. MEADOWS: Yes, yeah.

GROSS: Was it hard to get in?

Mr. MEADOWS: Again, I was lucky and I think that's something that I just

had

going for me my whole life, is that I've had these--I had lucky breaks. But

I

auditioned for Second City one time and I got hired for it, which doesn't

happen a lot. And I was immediately bumped up to the main-stage cast after

a

year of touring, which also doesn't happen a lot.

GROSS: How did you end up getting on "Saturday Night Live?"

Mr. MEADOWS: Lorne Michaels and Jim Downey, the producers of the show--they

were coming out to Second City to see Chris Farley, who was also in my cast.

And Chris and I were really good friends and we also performed a lot of

sketches together. And so they just--they happened to notice that there was

another guy on stage with Chris and that guy was me. And they--you know,

thought that I had some talent and they hired me about, you know, three or

four months after they hired Chris.

GROSS: Do you miss "Saturday Night Live?" You know, the season has started

without you this year.

Mr. MEADOWS: That's right. Yes, I do miss it. And I did the first

show--did a weekend update piece as Leon Phelps. And the audience was--they

were very nice and they gave me a big round of applause when I came out and

it

almost felt like they knew that I wasn't coming back anymore and they were

saying goodbye. And I almost got choked up. I got choked up. And I almost

cried because I could sense they were saying goodbye and it was a really

cool

connection that night.

GROSS: Well, Tim Meadows, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. MEADOWS: It's a pleasure to be here. I enjoy your show.

GROSS: Tim Meadows co-wrote and stars in the new movie "The Ladies Man."

He

co-stars in "The Michael Richards Show," which premiers tomorrow night. I'm

Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Author Robert Sullivan discusses his new book "A Whale

Hunt"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

It's not easy to re-create an ancient tribal tradition, especially when it's

controversial and has attracted angry protesters and media from around the

world. This was the scenario when the Makah, a small Native American tribe

at

the northwest tip of the US, decided to revive its 2,000-year-old whale

hunting traditions. The tribe had abandoned whale hunting in the 1920s

because of the scarcity of gray whales, but when these whales were taken off

the Endangered Species List, the Makah decided to exercise their treaty

rights

and revive the hunt. The government and the International Whaling

Commission,

the IWC, gave their approval to hunt a limited number of gray whales.

In the new book "A Whale Hunt," my guest Robert Sullivan writes about the

whole scene that grew around the subsequent whale hunt. Sullivan was living

in Portland at the time. He's now living in Brooklyn, New York. His first

book, "The Meadowlands," was about the New Jersey marsh that he described as

once the largest garbage dump in the world. I asked Sullivan why the Makah

wanted to start whale hunting again.

Mr. ROBERT SULLIVAN (Author, "A Whale Hunt"): They'd always whaled. And if

you talk to anthropologists, they'll give you dates, like, thousands of

years

ago the Makah started whaling. But if you talk to somebody in the tribe,

they'll say they whaled longer, since something like the beginning of time,

since forever. And whaling was their whole entire being. Whaling was

everything about their society, everything about their economy. They were

whalers. It made them who they were.

And then when the whales came back, when the gray whale came off the

Endangered Species List a few years ago, they decided that it would be a

good

time for them to try to whale again, to try to get that part of their

culture

back. So they saw it as this sort of, you know, comeback of their being, of

the centerpiece of their culture.

GROSS: So you have the Makah starting to whale hunt again because it was

such

a part of their past spiritually, culturally, economically. On the other

side, you have the animal rights groups who are arguing that whales

shouldn't

be slaughtered. What was their argument?

Mr. SULLIVAN: Well, their argument was--there was one argument that was

like

a legal argument that said that the IWC didn't actually sanction the hunt.

And I, frankly, found that difficult to follow. There were teams of

reporters

covering the hunt from Seattle and from Portland: newspaper reporters,

radio

reporters, TV reporters. And they were all trying to track that down. And,

you know, it became very--a political question: Is it sanctioned by the IWC

or isn't it? And some people felt it was, and some people felt it wasn't.

But, basically, the crux of the conflict came down to, you know, people

coming

in and protesting the whale hunt, saying, you know, `Sure, you used to

whale.

That used to be your tradition. But now you shouldn't do it anymore because

everything's changed, and whales are generally an endangered species. And

if

you start whaling,' some people argued, `even if you're just doing it for

your

tribe'--although some people argued that the Makah were going to try to sell

meat to Japan and start a commercial whaling setup. These people argued

that,

`Even if you just do it for your tribe, it will begin this, you know,

landslide of whaling. Whaling will just start again all over the world.

And

all the steps that we've taken to preserve whales, to save whales, will be

for

naught.'

GROSS: Robert, you're a kind of urban guy yourself. I mean, your previous

book was on the Meadowlands, which is like a large, urban marsh that is part

garbage dump.

Mr. SULLIVAN: And you're putting it kindly ...(unintelligible).

GROSS: Thank you, yes.

Mr. SULLIVAN: OK.

GROSS: So what's the importance of this whale hunt to you, and where do you

enter this picture?

Mr. SULLIVAN: Well, one day I heard on the radio that this tribe was going

to

start hunting whales again, and I remember hearing that they hadn't hunted

whales in a whole generation. And the first thing that struck me was,

`Well,

I can't imagine trying to re-create a ritual,' you know. `How difficult is

that going to be, and what does that entail?' Because, you know, I keep

equating it--you know, I was raised Catholic, you know, Irish-Catholic, and

I

always imagined, like--I keep imagining somebody coming to me and saying,

`Hey, you know, apparently we used to do this thing. It was called

Communion.

It involved a guy--there was a guy on a cross--I don't know. But we used to

do it, you know, a long time ago. Nobody remembers how it goes. We're

going

to do it again in about a year. You get it set up. Here's some other guys.

Do it all together. We'll be covering you live on TV when you do do it, if

you do it, and good luck to you.' And so that sort of appealed to me

initially.

And then the second thing was that I looked at the map, and I saw where this

place was. And this place is on the absolute edge of America, the very

northwest tip, you know. I always think of it as the bow of a ship, as the

very tip of the ship that, you know, you'd crawl out and watch the water

coming under the continent if it were, in fact, a ship. And I just looked

at

it on the map, and it's just one of those places that you look at on a map.

And I'm sure you--maybe you've--I'm pretty sure everybody looks at a map and

says, `I got to go there.'

And the next day an editor called me up and said, `You know, there's this

story, and I heard about it, and we immediately thought of you.' So I went

there, and--how did you put the question again because there was another

dimension to it that I want to...

GROSS: Oh, that you were urban.

Mr. SULLIVAN: Well--oh, yeah, that's right. OK. All right. So may I

address that part?

GROSS: Absolutely.

Mr. SULLIVAN: A lot of people said, `Yeah, you know, you were doing--you

were

canoeing through garbage dump-type creeks in New Jersey. Is this a natural

next step, you know, covering a whale hunt on the coast of a peninsula?'

And

at first I sort of said no, although someone pointed out that there's a

canoe

involved in both stories, and that is certainly true.

But, you know, the thing about this place, about Neah Bay, is that it

is--it's

classically beautiful. I mean, the coast is so beautiful. But when you

drive

into the town, it's part classically beautiful, but it's also a little town

that's very much a rural place. And, you know, I think I talk about how the

peaks that are the last peaks before the ocean are half-logged, you know.

And

so it's sort of this shopworn quality that I actually think is also

beautiful.

And, in a way, it's really secret and far away. And even though it was live

on TV, you know, during the whale hunt itself, even though there were

helicopters hovering over it and the "Today" show was filming live from in

front of the diner, even though it seemed to be being covered so

extensively,

it was still this secret little place that nobody knew about.

And that's kind of what the Meadowlands is, too. The Meadowlands is this

place that everybody just figures, `I don't need to know about it. I pass

by

that. I know all I need to know about that place.' And in a way, that's

kind

of how I felt about Neah Bay. I felt like people were saying, `Well, I know

that place. I don't need to know more about that. And I'm going to make my

mind up about this because I think I know what they're thinking.' And I

think

that's how they're related for me, is that they're two sort of secret and

special places. And yet I think you have to care about places, you know.

You

have to care about them, especially the places that people really don't

necessarily care about a lot right away.

GROSS: My guest is Robert Sullivan, and his new book "A Whale Hunt" is

about

the Makah in the Olympic peninsula on the West Coast, who decided to hunt

whales again because their culture was so bound up in it. But Sullivan also

writes about all the other cultures that came out for the hunt: the media,

the animal rights protesters, the people from various bureaucracies and

agencies who were monitoring the beginning again of the whale hunt.

The members of the Makah, who went out in the canoe to hunt the whale, had

with them a harpoon and a gun. How did they decide to have this combination

of the harpoon, which represents the traditional Native approach to hunting

whales, and the gun, which was, you know, a pretty modern gun that they had?

Mr. SULLIVAN: Well, part of the reason they had a gun was that when they

went

to the International Whaling Committee, they said that they would hunt the

whale `humanely.' That's the word that was used. And, of course, that's a

word that people picked up and said, `Well, how is it humane to use a gun to

kill a whale?' But the sort of idea of it was that they'd harpoon the

whale,

traditionally if you will, and then they would kill the whale with a gun

because, you know, in the old days, I gather that a whale harpooned might

have

run the canoe around on what Nantucketers call `the Nantucket sleigh ride,'

and they would just basically wait until the whale died this slow death.

And

the idea was that they would put the whale out--to use a phrase that people

use--`out of its misery' by using a gun.

This, of course, was a huge point of controversy, this idea that it would be

traditional if they weren't using a gun. And I found this a fascinating

discussion because, OK, it's traditional to use the harpoon, but it's not

traditional to use a gun. But you often wonder if they had had a gun in,

say,

the year 1600, would they have used the gun? And there's this notion that

technology has to be--you know, technology is new. Only new technology is

technology. And traditional stuff is old, and you can never have newness in

oldness and things like that.

My feeling is that technology is--if something new comes along, people want

to

use it. But this is the kind of discussion that I think that the gun

brought

into it. A lot of people just thought, `Oh, gun? Forget it. They

shouldn't

use a gun on the whale.'

GROSS: So did they end up using both on the whale hunt?

Mr. SULLIVAN: They ended up using both on the whale hunt. Of course, it

was--you know, some people said, `We should just go out with a gun,' in the

tribe, and some people said, `We should only use a harpoon.' And some

people

in the tribe said, `We shouldn't hunt whales at all.' And some people said,

`We should hunt whales, but only once in a great while.' And it wasn't

always

the case that there was one voice. And, of course, there was a lot thinking

in all camps, but it kept getting all sort of summarized into, `There go the

Makah,' and, `There go the protesters.' And that just fueled, you know,

anger

and upsetedness.

GROSS: My guest Robert Sullivan is the author of "A Whale Hunt." We'll

talk

more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest Robert Sullivan is the author of "A Whale Hunt." It's

about

what happened when the Makah tribe revived its whale hunting traditions and

angry protesters, as well as media from around the world, arrived.

When you were talking to the guys who were actually on the whale hunt in the

canoe, knowing that hunting a whale can be pretty dangerous, you know,

particularly when your harpoon is attached to the whale, and the whale's

kind

of freaking out because it's been struck, were they afraid that they would

get

hurt or perhaps killed in the process?

Mr. SULLIVAN: You know, the captain--I watched the captain quite a bit, and

that was all he could think about in the end, it seemed to me. He was so

worried that somebody would get killed, and he was worried that maybe one of

the protesters might get killed in the middle of guns and harpoons and

everything.

But, you know, I remember some moments just standing there in the rain, on

the

beach, talking about what would happen. I remember one of the guys said,

`You

know, we were talking to some whalers, some guys who are, you know'--it's an

aboriginal nation up off the coast of Russia--`and they said that if you

fall

in the water while you're whaling, the gray whale will come up and look at

you,' you know, as if you're sort of a jewel being dangled in front of its

eyes. And they heard that the whale can get really angry, and it'll come

after you sort of vengefully.

And they would tell these stories and then not say anything, and the idea of

a

whale coming up and looking at you and being angry, that idea would just

resonate.

GROSS: Would you describe a little bit about what happened during the first

successful whale hunt, where they actually killed a whale?

Mr. SULLIVAN: During the first whale hunt--and as far as I know, it's the

only whale hunt they've successfully completed, you know, since they've

brought back this tradition--well, that whale hunt was just this spectacular

event, spectacular not just because this tribe was going through with this

modern re-creation of an ancient ritual, which in itself is incredible--I

mean, an amazing feat--but it was also this--you know, all the press that

was

there, all the attention to it, all the sort of swirling controversy right

there in the water.

You could see from--as I happened to be on the peaks, you could see it from

the peaks. You could look down and see the coast of the Northwest, and you

could see the streak of the canoe and the sort of blur of the gray whale,

and

you could see the spiraling froth of the protest boats trying to get in,

maybe

trying to stop it. And you could see the Coast Guard on the edge of this

sort

of trying to figure out what to do. And it was really an amazing clash of

of

a culture that said, `We're not sure we want whales to be hunted'; of a

culture that said, `We're going to get this live on the news tonight'; and

of

a culture that said, `We're going to do this because this is in our treaty,

this is our right and we're entitled to do this.' It was this clash of

those

things that was right there on the water that was, you know, made event.

GROSS: Having watched the people who did participate in the whale hunt, do

you think--I know you don't feel like it's your position to judge, but did

they say anything to you about feeling that it was a transformative

experience

in any way?

Mr. SULLIVAN: You know, one of the guys on the whaling crew, one of the

guys

who a lot of people didn't think could even sort of do it, could pull it

off,

he went through this, as a lot of guys did, saying, `You know, after this is

over, everything's going to be different. I'll be able to go where I want

and do

do what I want to do, and my life's going to change.' And I keep talking

about it as a ritual, but this is what you look for in rituals. You know,

you

want to go in and do something, and you want to feel better at the end of

it.

But as a matter of fact, when it was all over, just this one guy that I kind

of know had trouble figuring out what was going to happen, what he was going

to do. And, in fact, he couldn't go anywhere. He couldn't go--if he wanted

to go to Seattle and go to a restaurant, he was maybe kicked out, you know.

And his relatives, some of their doctors didn't want them to show up

anymore.

He couldn't show up in Victoria. He'd be told to get lost.

GROSS: Because of the controversy over the whale hunt?

Mr. SULLIVAN: Because he was a whale hunter. And I think that, you know,

there was, for just this one guy I know, disappointment and confusion, as

there would be. But I can report that this guy, anyway, after some time

thinking about it, ended up kind of figuring out what to do, and he got a

job

and he got his sort of own little business going recently, and things are

good

for him, for that one person, which, you you---I mean, it took about two

years

just to be able to even say that.

So the idea that I could even--you know, because the people often say,

`Well,

did it help the tribe? Did it help the whole town?' Well, my gosh, can you

imagine how many years it would take for me to be able to say a little tiny

bit about that, about--you know, for the tribe? I could never know. But

just

the one guy that I know, he came out of it toughened in a way, and he's got

a

job.

GROSS: But it sounds like some of what you're talking about has more to do

with the controversy about whale hunting than the experience of hunting the

whale and thinking about whales and going back to this ancient tradition.

Mr. SULLIVAN: Well, the experience and the controversy, I don't think--the

way he ended up is partly due to the experience. I mean, if I was just

going

to say, I'd say three-quarters of it was the experience, but a quarter of it

was the controversy, but the controversy was in this case the experience.

And

the modern traditional whale hunt, the version of a whale hunt that

happened,

was--you know, part of that was--you know, if you're a sailor, it was the

idea

of tacking the wind of the media, you know. It was the idea that, OK, it

used

to be you'd have to go out and look at the moon and figure out the tides,

but

not you've got to also figure out where the protesters' boats are going to

be

docked on Thursday.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SULLIVAN: I mean, why is that any less of a challenge, in a way, or why

is that not part of the mix, you know what I mean?

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. SULLIVAN: And so I don't think you can--in this case, I don't think you

can really separate the controversy from the experience. I mean, the

experience was heightened by the controversy. You know, an amazing thing

happened. The first time they went to hunt a whale in October of, I think

it

was, '98--the first time they went to hunt a whale, they didn't hunt a

whale.

And they had all the TV cameras there, and all the microphones were in their

face, and they didn't do it. And to me, that was an amazing thing because

to

be an American today, to be a citizen of the world today and to have a

television camera on you and for you to not do something, that in itself is

a

singular achievement. That's incredible. You put a camera on me right now,

I'd do whatever you wanted probably. You know what I mean? That's amazing.

GROSS: Robert Sullivan is the author of "A Whale Hunt." In June, the US

Court of Appeals 9th District ruled that the federal government had failed

to

adequately review the environmental effects of a whale hunt, and therefore

the

Makah should stop hunting until a decision is made in a federal court in

Tacoma. That decision could take several months. In the meantime, the

Makah's legal team says that their 1855 treaty with the government gives

them

permission to whale.

Coming up, TV critic David Bianculli reviews the new show "Boston Commons"

and the season premiere of "Ally McBeal." This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Fox premiering new show "Boston Public" with "Ally McBeal"

TERRY GROSS, host:

Tonight on the Fox Television Network, writer/producer David E. Kelley

assumes

responsibility for the prime-time Monday lineup. Not only does his "Ally

McBeal" series return for its fourth season, but Kelley's newest show

premieres. It's a comedy-drama about teachers at a public high school in

Boston. TV critic David Bianculli has this review.

DAVID BIANCULLI reporting:

I'm a huge fan of David E. Kelley's writing, but even I'll admit last year

wasn't one of his strongest seasons. Both "Ally McBeal" and "The Practice"

got sidetracked and often silly, while the shows his company produced but

which Kelley had little to do with, "Chicago Hope" and "Snoops," got

canceled.

To start the new season, Kelley has hit the ground running. A new season of

"The Practice" with a three-part story arc that's no-nonsense, all law and

all

entertaining already has been unrolled by ABC. And tonight Fox presents the

return of "Ally" and the first look at Kelley's newest effort, "Boston

Public." To get right to the point, they're both really good and really

worth

watching.

"Boston Public" is a show that looks at high school from the point of view

of

the faculty. More "Room 222" than "Dobie Gillis" or "Beverly Hills 90210."

The beleaguered but admirable head of the school, a principal with

principles,

is played by Chi McBride. He's sort of a high school equivalent of Frank

Furillo. And for McBride, it marks what may be the fastest and best career

turnaround in modern TV history. He's bound to get lots of well-deserved

attention and acclaim for his role here, but two years ago he got a lot less

acclaim as the star of that tacky and controversial slavery-era UPN sitcom

"The Secret Diary of Desmond Pfeiffer." In the "Boston Public" press kit,

"Desmond Pfeiffer" isn't even mentioned. It was that bad a `pflop.'

But McBride makes a really good first impression here, as do other actors

portraying members of the faculty and student body. One of them, Fyvush

Finkel from Kelley's "Picket Fences," is very familiar. Others are not, but

should be before long. And the characters they play aren't all noble Mr.

Know That types either. When one young teacher, played by Nicky Katt, is

assigned substitute duty in the school's toughest classroom, even the

teachers

call it the dungeon. He gets their attention by removing his coat and

revealing a holster and handgun.

(Soundbite from "Boston Public")

Mr. NICKY KATT (As Harry Senate): Take your seats, please.

(Soundbite of student chatter)

Mr. KATT: What's up? Everybody got really quiet. What's the deal? It's

not

this, is it? What? This you respect? Hey, Mr. Scott, tell me, why'd you

get

quiet for this?

Unidentified Actor (As Mr. Scott): 'Cause that could kill me.

Mr. KATT: 'Cause that can kill you. See? You respect that. And we like

seeing people get popped, don't we? My favorite movie, "The Godfather,"

even

the good guys go around shooting each other in the head. Same thing with

"The

Sopranos." `Hey, Tony.' `Yeah?' Pop. That's entertainment. Brings us

pleasure. Even the word `gun,' that's got a pretty good sound to it,

doesn't

it?

BIANCULLI: Meanwhile, over on "Ally McBeal," the first two episodes of the

season benefit greatly from charismatic guest stars. One is Marcia Cross,

formerly of "Melrose Place," portraying a woman accused of sexual

harassment.

The other is Robert Downey Jr., whose character, Larry Paul, is found by

Calista Flockhart's Ally when she goes to visit her therapist, Tracey.

Downey

will be featured in many episodes this season, and he and Flockhart work

great

together.

(Soundbite from "Ally McBeal")

Mr. ROBERT DOWNEY Jr. (As Larry Paul): Help you?

Ms. CALISTA FLOCKHART (As Ally McBeal): I'm looking for Tracey.

Mr. DOWNEY: Oh, she doesn't work here anymore. She moved to Foxboro.

Ms. FLOCKHART: Foxboro? She didn't tell me she was moving.

Mr. DOWNEY: You wouldn't be Ally McBeal, would you?

Ms. FLOCKHART: Yes, I would actually. How did you know that?

Mr. DOWNEY: She took all her files, except one, Ally McBeal. It's a catchy

theme song, by the way. I'm Larry Paul...

Ms. FLOCKHART: God! She took every file, but she left mine?

Mr. DOWNEY: Yeah, with a note. `If it's an emergency, tough.'

Ms. FLOCKHART: This is an emergency. Now please give me her number.

Mr. DOWNEY: She didn't leave it, promise. What's the problem?

Ms. FLOCKHART: Well, there's--umm--well, it's--there's the--there's a guy

that I've been seeing, and he asked me to move in with him.

Mr. DOWNEY: Bastard. My advice is not do it.

Ms. FLOCKHART: Why?

Mr. DOWNEY: The guy obviously doesn't want to marry you.

Ms. FLOCKHART: How do you know that?

Mr. DOWNEY: Well, did he ask you to marry him?

Ms. FLOCKHART: Well, what makes you think that I want to marry him?

Mr. DOWNEY: Because you don't seem like the mistress type. If you're going

to

move in with a guy you have no intentions of marrying...

Ms. FLOCKHART: I never said that I had no intentions.

Mr. DOWNEY: Are you a mistress?

Ms. FLOCKHART: No, I am not a mistress.

Mr. DOWNEY: Then why live with a guy who's afraid to marry to you?

Ms. FLOCKHART: How do you know he's afraid?

Mr. DOWNEY: Because he didn't ask.

Ms. FLOCKHART: Look, I am here for my own indecision, not his.

Mr. DOWNEY: How's the sex?

Ms. FLOCKHART: Excuse me?

Mr. DOWNEY: With your friend. The sex?

Ms. FLOCKHART: Well, I don't care to talk about that.

Mr. DOWNEY: Ooh, it's that good, huh?

Ms. FLOCKHART: Look...

Mr. DOWNEY: Ally, none of my business, but every relationship will

eventually

come down to sex. Why? Because men and women are different animals with

different interests. Don't believe all that communication crap. No matter

how much in love, men and women eventually run out of things to say to each

other, and when that happens, all you'll be left with is sex. If it stinks,

you're done, and I don't need to tell you that, do I? That's why you're

here.

The sex is lousy.

BIANCULLI: The tone of "Ally" has returned to where it started. The few

fantasy sequences come as true surprises again. There is more voiceover

revealing Ally's thoughts, and there's enough realism to make you care about

the characters and their emotional pain.

"Ally" and "Boston Public" make for a terrific one-two punch on Monday

nights,

and tonight it's a pair of punches you ought to plan on taking.

GROSS: David Bianculli is TV critic for the New York Daily News.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.