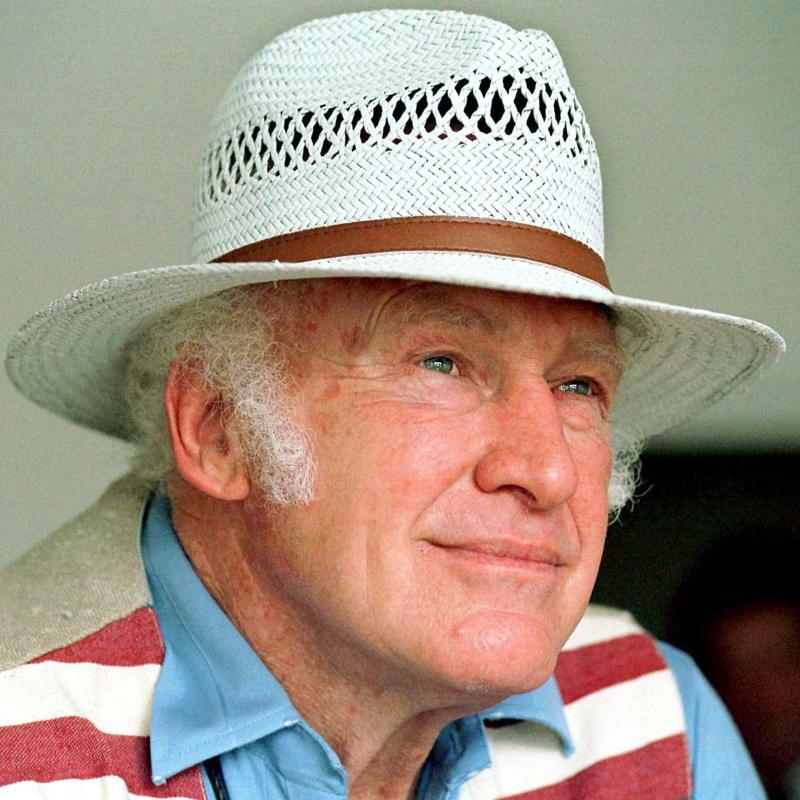

Ken Kesey On Misconceptions Of Counterculture

The new documentary Magic Trip follows the late Ken Kesey and the Merry Band of Pranksters as they criss-crossed across the United States during the tumultuous 1960s. Kesey joined Terry Gross in 1989 for a conversation about the counterculture movement and his writing.

Other segments from the episode on August 12, 2011

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20110812

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Writer Robert Stone Relives Counterculture Years

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli of tvworthwatching.com, in for Terry

Gross.

The new documentary "Magic Trip: Ken Kesey's Search for a Kool Place," gathers

never-before-seen footage shot during LSD-fueled bus trip across America in

1964 by a group known as the Merry Pranksters. Ken Kesey, the author of "One

Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," was the ring leader. The bus was driven by Neal

Cassady, who was the inspiration for the main character in the Jack Kerouac

novel "On the Road."

On today's Fresh Air, we'll hear interviews Terry recorded with Ken Kesey; with

Tom Wolfe, who chronicled the bus trip in his early bestseller "The Electric

Kool-Aid Acid Test"; and with Robert Stone, who spent time with Kesey, Cassady

and the Pranksters when their bus rolled into New York.

The new film is directed by Alex Gibney and Alison Elwood. Gibney also directed

the 2008 Oscar-winning documentary "Taxi to the Dark Side" and the 2006 Oscar-

nominated documentary "Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room."

"Magic Trip" uses old footage shot by Kesey and the Pranksters to document

their cross-country journey. The film also uses archival audio recordings,

including excerpts from Terry's interview with Kesey. This clip from the film

starts with Kesey describing how he first encountered psychedelic drugs during

government-sponsored drug experiments. It also includes some of Terry's

interview with Kesey and additional archival sound of a report on the

government drug experiments.

(Soundbite of film, "Magic Trip: Ken Kesey's Search for a Kool Place")

Mr. KEN KESEY (Author, "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest"): I came out of the

University of Oregon the prettiest little boy you've ever seen. I didn't smoke.

I didn't drink. I went to Stanford on a Ford Foundation fellowship. And while

at Stanford, I was given the opportunity to go to the Stanford Hospital and

take part in the LSD experiments.

TERRY GROSS: How did you become a volunteer for these experiments?

Mr. KESEY: I, at the time, was training for the Olympics team and was...

GROSS: As a wrestler?

Mr. KESEY: Yeah, as a wrestler. I'd never been drunk on beer, you know, let

alone done any drugs. But this is the American government.

Unidentified Man #1: The study of LSD continues in laboratories and hospitals

throughout the United States.

Mr. KESEY: They paid us $25 a day to come down there, and then they gave us

stuff.

Unidentified Man #2: What is LSD? How does it work? When did it all begin?

Unidentified Man #1: It all began in a laboratory very much like this one. In

1938, Dr. Albert Hofmann, in Switzerland, was looking for new drugs in the

treatment of migraine headaches.

BIANCULLI: A clip from the new documentary "Magic Trip." In 2007, Terry spoke

with writer Robert Stone about his memoir "Prime Green." Much of the book is

about his experiences with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranskters. Stone won a

national book award for his 1974 Vietnam novel "Dog Soldiers," which was

adapted into the film "Who'll Stop the Rain?"

GROSS: Robert Stone, welcome back to FRESH AIR. I'd like you to read an excerpt

from your new memoir, "Prime Green," but I'd like you to set it up for us.

Mr. ROBERT STONE (Author, "Prime Green"): All right, well, the scene takes

place in the summer of 1964, when Kesey and the people who had become known as

the Pranksters took a International Harvester school bus across the country,

the bus painted many colors and featuring runic slogans and so on.

And I was, at that time, living with my wife and kids in New York, and we were

expecting the bus, and sure enough, the bus pulled up in front of our apartment

house. My daughter still remembers being taken down the stairs by a man painted

completely green. And we rode around the bus. We rode all over New York. We

rode through Central Park, dodging tree trunks and being yelled at by cops and

anybody who felt like yelling at us.

And we ended up, that evening, at a party on the Upper East Side, which was a

kind of a reunion of or a meeting of our generation, that is Kesey's California

gang, and some of the old beats who were Cassady's friends. Cassady had driven

the bus, I should say, Neal Cassady, who was the prototype for Dean Moriarty in

Kerouac's "On the Road" - he'd driven the bus cross-country.

At that party â well, Kerouac was there, and Ginsberg was there. It was a very

difficult party because of a number of tensions, particularly I think Kerouac's

jealousy, for lack of a better word, over Neal Cassady's having been

appropriated by Kesey and the bus. So it was not altogether a happy occasion.

GROSS: Would you read that section for us now?

Mr. STONE: Yes. There was the after-bus party, where Kerouac, out of rage at

health and youth and mindlessness, but mainly out of jealousy at Kesey for

hijacking his beloved sidekick Cassady, despised us and wouldn't speak to

Cassady, who with the trip behind him, looked about 70 years old.

A man attended who claimed to be Terry Southern but wasn't. I asked Kerouac for

a cigarette and was refused. If I hadn't seen him around in the past, I would

have thought this Kerouac was an imposter, too. I couldn't believe how

miserable he was, how much he hated all the people who were in awe of him.

You should buy your own smokes, said drunk, angry Kerouac. He was still

dramatically handsome then. The next time I saw him, he would a red-faced baby,

sick and swollen. He was a published, admired writer, I thought. How can he be

so unhappy? But we, the people he called surfers, were happy.

GROSS: That's Robert Stone, reading from his new memoir, "Prime Green:

Remembering the '60s." You first read "On the Road" when you were in the Navy

in 1957. Your mother sent it to you. What did the book mean to you in the Navy?

Mr. STONE: My mother was - as you can imagine from her sending me that book, a

very socially tolerant person. I didn't admire it as prose fiction, I have to

say, even though I was still under the spell of Thomas Wolfe, and this reminded

me somewhat of Thomas Wolfe. But the world that it projected, the world of the

road, that great American romance with the horizon and the roads west and all

of that, that got to me. That moved me. And when he grew lyrical about that, he

had me with him.

GROSS: Now, you got out of the Navy in 1958, and then you eventually got a

fellowship, a Wallace Stegner Fellowship, to Stanford University, which got you

to move from New York to the West Coast.

And there you met Ken Kesey, and you were introduced to LSD and introduced to

Kesey's whole crowd of people that became known as the Merry Pranksters. They

were the subject of Tom Wolfe's book "Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test." How did you

meet this group of people?

Mr. STONE: Well, I got into Wallace Stegner's writing class, and a lot of

friends of Ken were in that class. Ed McClanahan, I think a writer named Ed

McClanahan, first took me around to Perry Lane, which was a street of bungalows

of the sort that Menlo Park and Palo Alto were filled with in those days,

before California real estate.

It was a street where - undergoing a cultural transformation from the days of

plonky(ph), red wine and sandals to psychedelia and strangeness, and the master

of the revels with all that was Ken Kesey.

And Kesey was a remarkable character. You didn't have to be much of a

psychologist to see that this was an extraordinary individual, with an enormous

amount of energy and drive and imagination, and he was simply a lot of fun.

And the people that I met there were a new breed for me, in a way, because even

though I had read a great deal, I did not come from a milieu in which books and

art was much discussed. I had gone to parochial schools in New York. They were

very good for learning grammar and even for learning the Latin, but the thrust

was pretty anti-intellectual.

Well, I had been in the service from the age of 17, hardly an intellectual

environment. So to get out among people who knew - really knew how to have fun

and were also culturally sophisticated, it was a wonderful experience for me. I

felt grateful. I felt, you know, that something really special had happened to

me.

And California in the early '60s, I mean that is a place I am really tempted to

romance about because it seemed like a garden without snakes. It was - for

somebody coming from New York, it was so mellow, it was - life was so

easygoing. It was not expensive then. The company was first-rate. It was a

great place to be young, and I still feel grateful for being there.

GROSS: As a writer, what was it like to be part of a group that was

mythologized by Tom Wolfe's book "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test"? And were

you one of the characters in the book who was mythologized?

Mr. STONE: I'm one of the characters in the book. I make a couple of

appearances. One thing that impressed me about Wolfe's book was how precisely

he managed to project what was pretty ineffable. I mean, it was very hard to

explain to anyone what Kesey's scene was like and what it was about.

I mean, it would have been very hard for any of us to explain to each other,

you know, what on Earth we were doing. And Wolfe sort of caught the range, it

seemed to me, as well as anyone could who was as utterly outside it as he was.

I suppose because he had a certain sympathy for the native grain and its

antics, that might have inclined him to Kesey and the gang because they were so

un-New York, maybe. I think he did rather a good job. I mean, he - I think his

nonfiction books are quite good.

BIANCULLI: Author Robert Stone, speaking to Terry Gross in 2007, about his

experiences with the Merry Pranksters. We'll hear more from Robert Stone and

also hear from author Tom Wolfe after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

BIANCULLI: Let's get back to Terry's 2007 interview with author Robert Stone.

While discussing his memoir "Prime Green," the Vietnam veteran also talked to

Terry about the time he met Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters as their magic

bus arrived in New York.

GROSS: Neal Cassady, who was a friend of Kerouac's and is the inspiration for

the Dean Moriarty character in "On the Road," was a part of Ken Kesey's group

and usually drove the bus when people were traveling. Now, you describe Cassady

as often being on amphetamines, and you say when he was on amphetamines, he

never ate, he never slept, and he never shut up.

Mr. STONE: Yes, that was about the situation. Moreover, he had a parrot, called

Rubiaco(ph), and when you walked into a room, this rap would immediately begin.

You could never be absolutely certain whether it was Cassady or the parrot.

Many years later, my wife and I were up at Kesey's in Oregon, this is after

Cassady was gone, and we woke up to see this fiendish-looking parrot walking

over us, and for one brief moment, the parrot went into this rap. It was

something like: The last time I was in Denver, you think those cops...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. STONE: It was a little shard of Neal Cassady remaining in the world, all

that was left in the universe of Neal. But, you know, I never knew him at his

most beautiful. You know, he was pretty wrecked by amphetamines when I knew

him. And, you know, I have to believe that, you know, the people who idealized

him and saw him at his best, you know, saw someone great. But unfortunately,

when I knew him, he was pretty out of it.

GROSS: When you were on Kesey's bus, and Cassady was driving, did you feel

safe, I mean, knowing that chances were he's probably on amphetamines of

something else, and he was supposed to be like a really fast driver, driving

fast around twisting roads and so on?

Mr. STONE: It never occurred to me, and I wonder if it occurred to any of us to

ever feel unsafe with Neal driving. Neal was a driver of heroic proportions. I

mean, it was said of him that he could steal a car, roll a joint and back the

car out of the smallest possible space, all in seconds.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. STONE: So we always thought he was heroic as a driver. I don't think we -

many of us had a moment's anxiety.

GROSS: And you also write: Cassady thought it a merry prank to slip several

hundred micrograms of LSD into anything anyone happened to be ingesting. Did

you see that as being kind of funny and whimsical or as, like, dangerous and

maddening?

Mr. STONE: I saw it as an act of violence. I - you know, that was not a prank

that I had much sympathy for because you never knew what anybody's reaction

might be, you know, even if you knew them pretty well. That was something I

didn't go along with, and I didn't think it was funny.

I mean, it's - you know, it makes an amusing tale in retrospect, sort of,

because it didn't turn out badly, but no, I did - I thought it was an act of

violence, simply put.

GROSS: Did he pull that on you, and did you find yourself suddenly

hallucinating without being mentally prepared for it?

Mr. STONE: It happened to me a couple of times, and I suspect that Neal was

behind it. And it was always a very tiresome prospect, if you hadn't brought it

on yourself.

I mean, taking acid was a lot of work. I remember one occasion in which I'd

taken it myself. I was perfectly responsible for everything. I woke up in the

morning after I'd finally got to sleep, and my jaws were aching. They were just

coming off, and I couldn't figure, you know, what was wrong with the lower part

of my face. And then I realized I'd been smiling for 12 hours.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. STONE: It was work.

BIANCULLI: Robert Stone, speaking to Terry Gross in 2007. His memoir is called

"Prime Green."

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

139239484

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20110812

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Tom Wolfe: Chronicling Counterculture's 'Acid Test'

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

Another person who recounted the events documented in the new film "Magic

Trip," about the Merry Prankster bus trip across America led by Ken Kesey in

1964, is Tom Wolfe. He wrote about the trip and Kesey's LSD experiments in his

book "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test."

Wolfe pioneered what came to be known as new journalism: reporting using the

techniques of fiction, descriptive scene settings, dramatic tension and

dialogue. When Terry interviewed Tom Wolfe in 1987, she asked him about his

trademark look, the tailored white suit. He told Terry that his attire wasn't

just about style, it also affected how he would go about his work as a

journalist.

Mr. TOM WOLFE (Author, "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test"): I have discovered

that for me - now maybe it doesn't work for everybody - for me, it is much more

effective to arrive at any situation as a man from Mars than to try to fit in.

When I first started out in journalism, in magazine work, particularly, I used

to try to fit in. I remember doing a thing on stock car racing. I went down to

North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, to do a story on a stock car racer named

Junior Johnson. And I tried to fit in to the stock car scene.

I wore a green tweed suit and a blue button-down shirt and a black knit tie and

some brown suede shoes and a round Borcelino hat. I figured that was really

casual, it was the stock car races.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WOLFE: And after about five days, Junior Johnson, whom I was writing about,

came up to me. He says, I don't mean to be rude or anything, he says, but

people I've known all my life down here in Ingle Hollow, that was where he came

from, he said they keep asking me: Junior, who is that little green man

following you around?

And it was then that it dawned on me that: A, nobody for 50 miles in any

direction was wearing a suit of any color, or a tie for that matter, or a hat,

and the less said about brown suede shoes the better, I can assure you. So I

wasn't - you know, I wasn't fitting in to start with.

I was also depriving myself of the ability to ask some very obvious questions

if I thought I fit in. I was dying to know what an overhead cam was. People

were always talking about overhead cams, but if you were pretending to fit in,

you can't ask these obvious questions.

After that, I gave it up. I turned up - always in a suit and, you know, many

times a white suit and just be the village information-gatherer. And you'll be

amazed, if you're willing to strike that role.

GROSS: When you were doing the research for your book "Electric Kool-Aid Acid

Test," which is about Ken Kesey and the psychedelic acid trips, were you

dressed like that, too?

Mr. WOLFE: Oh, yes, and actually, to try to have fit into that scene would have

been fatal, perhaps literally fatal.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WOLFE: Kesey had this abiding distaste for pseudo-hippies or hipster -

there was really no such term at that time, but we'll just call them pseudo-

hipsters, you know, the journalist or the lawyer or teacher who on the weekends

puts on his jeans and smokes a little dope and plays some Coltrane records and

tries to be part of the scene.

And so he had a device called testing people's cool. And I remember once

witnessing this. It was on one of these weekends. And he said: All right, let's

everybody get nekkid(ph) - that was his word for naked - and get on our bikes

and go up Route 1. This was in California.

And they did. They took off all their clothes, they got on their motorcycles,

and they started riding up Route 1. Now, this separated the hippies from the

weekend hipsters, if you will, very rapidly. But now I didn't have to worry

because I was in my three-piece suit with a big blue corduroy necktie, and the

idea that I was going to take any of this off for anybody was crazy.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. WOLFE: So, you know, I was safe.

GROSS: You probably just looked like another freak to a lot of freaks.

Mr. WOLFE: Well, after about two weeks, one of Ken Kesey's group, the

Pranksters, named Doris Delay, said to me: You know, you've got on the weirdest

outfit around here. And it was the most unusual in that particular little

corner of the woods.

BIANCULLI: Tom Wolfe, speaking to Terry Gross in 1987, talking about Ken Kesey

and Company. We'll hear from Ken Kesey himself in the second half of the show.

I'm David Bianculli, and this is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

139383916

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20110812

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Ken Kesey On Misconceptions Of Counterculture

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. Iâm David Bianculli in for Terry Gross.

Continuing our salute to "Magic Trip" the new documentary about Ken Kesey's

drug-fueled 1964 cross-country bus trip with a group he called the Merry

Pranksters, we now turn to Ken Kesey himself. Kesey wrote two novels that were

very popular in the 1960s, "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" and "Sometimes A

Great Notion."

At the time though, he was even better known for being one of the first people

to bring the experimental hallucinogen LSD out of the research laboratory and

into the counterculture. Kesey and his friends were among the first and most

celebrated of the West Coast hippies. In his book "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid

Test" Tom Wolfe described the escapades of Kesey and the Pranksters as they

drove around the country in their Day-Glo school bus.

Terry Gross spoke with Ken Kesey in 1989 and asked him what he thought about

Wolfe's book and how accurate it was.

Mr. KEN KESEY (Author): Oh yeah. Itâs a good book. Yeah, heâs a - Wolfeâs a

genius. He did a lot of that stuff, he was only around three weeks. He picked

up that amount of dialogue and verisimilitude without tape recorder, without

taking notes to any extent. He just watches very carefully and remembers. But,

you know, heâs got his own editorial filter there. And so what heâs coming up

with is part of me, but itâs not all of me, any more than Hunter S. Thompson is

loaded all the time and shooting machine guns at John Denver. Thatâs the sort

of thing - interesting in the media but heâs got a lot more life to him than

that.

GROSS: What effect that the "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test" have on you? For

instance, did it make the police feel more determined to try to bust you again?

Mr. KESEY: Yeah. But I havenât been worried about the cops that much. The

effect "Kool-Aid Acid Test" is theyâll say that youâre Richard Gere and youâve

got a great big wart on the side of your nose. And they begin to play it up in

the cameras and then pretty soon it becomes the thing that a lot of teenage

girls are in love with, and pretty soon youâre looking at it too, until youâre

cross-eyed looking at your own wart.

GROSS: Why do you use the wart as an analogy?

Mr. KESEY: Well, because I was a lot more than the Tom Wolfe depiction. And I

think this is a problem for a lot of American writers and has been for a long

time. You know, Hemingway, he really doesnât get into trouble until he becomes

dazzled by his own image. He sees the rest of the United States looking at him

and he moves over and sits there, and he looks at himself too. And then when he

tries to go back and get inside of his own skin he canât quite fit into it as

well as he used to; heâs gained weight.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. KESEY: He canât put his own skin back on. And when youâre writing, itâs not

a good idea to be observed too much. Unless you want to live in New York and

weâre white clothes.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. KESEY: If you really are interested in being a real straight old-fashion

writer, itâs better to live down in Mississippi like Faulkner and work out in

the woodshed and not be seen but once every 10 years. I think that being the

observed always turns your eye back on yourself and you become kind of blinded

by your own radiance.

GROSS: You started doing LSD through a government experiment. An experimental

program in, I think, it was in 1959. You were one of the volunteers who, you

know, volunteered to take this experimental drug and have it tested on

yourself. How did you become a volunteer for these experiments?

Mr. KESEY: One of the guys that was our neighbors, was a - he was a

psychologist and he was supposed to show up one day and just really he didnât

have the common hair to do it and says does anybody else like to take my place?

And I, at the time, was training for the Olympics. I made it to be an alternate

in the 1960 Olympics team and was...

GROSS: As a wrestler?

Mr. KESEY: Yeah, as a wrestler. Iâd never been drunk on beer, you know, let

alone done any drugs. But this is the American government. They said, come in

here. Weâve just discovered this new spot of space and we want somebody to go

up there and look it over and we donât want to do it. We want to hire you

students. And I was one of 140 or so that eventually turned out. It was CIA

sponsored. I didnât believe it for a long time. Well, Allen Ginsberg said you

know who was paying for that was the CIA. I said all no Allen, you're just

paranoid. But he finally got all the darn records and it did turn out the CIA

was doing this. And it wasnât being done to try to cure insane people, which

is what we thought. It was being done to try to make people insane - to weaken

people and to be able to put them under the control of interrogators. We didnât

find this out for 20 years. And by that time the government had said okay,

stopped that experiment. All these guinea pigs that we sent up there and outer

space bring them back down and donât ever let them go back in there again

because we donât like the look in their eyes.

GROSS: Do you remember what your very first trip was like when you were a

volunteer in this government program? And what kind of preparation were you

given for it? Were you given any?

Mr. KESEY: None at all. Except I read a little piece in Life magazine about how

theyâd given it to cats and cats were afraid of mice once they had LSD. But I

think that weâd been preparing for a long time. You know, I knew the Bible. I

knew the Bhagavad Gita. I knew the Daodejing. I had read Hermann Hesseâs

âJourney to the East,â which gave us an underpinning, spiritually, so that

these phenomena that were happening to us had something that they could relate

to. We just happened to come at a time when it was not only a lot of stuff

happening, chemically, there was a lot of new changes in music and in film.

Burroughs was just beginning to do his work in literature and there was a

movement afoot that this was just a part of.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. KESEY: And it was exciting. It was wonderful.

GROSS: What was the very first trip like, though, under the experimental

conditions?

Mr. KESEY: Groovy, man.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. KESEY: It was groovy. We suddenly realized that thereâs a lot more to this

world than we previously thought. I think, you know, because Iâm asked this

question a lot. Itâs been 20 years or so and people are always coming back

saying well, what you think? And Iâm - the one of the things that I think came

out it is this that thereâs room. We donât all have to be the same. We donât

have to have Baptists, coast to coast. We can throw in some Buddhists and some

Christians, and people who are just thinking itâs these strange thoughts about

the Irish leprechauns, that there is room, spiritually, for everybody in this

universe.

GROSS: You were among the first people to take LSD at of the clinical setting

and use it in a social setting. How did you first get it out?

Mr. KESEY: Of the hospital?

GROSS: Yeah.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. KESEY: Well, after I had gone through these drug experiments and was in

this little room in the hospital, looking out through the little window at the

people out there who were the regular nuts. They werenât students going to

experiments. Iâm looking at them through my crazed eyes, I saw that these

people have something going and thereâs a truth to it that people are missing.

And thatâs how I came to write âCuckooâs Nest.â I got a job at the nut house

and worked from midnight to eight writing that book and taking care of these

patients on this one ward and made a lot of good friends â some that I still

have. And I found that my key opened a lot of the doors to the doctorâs offices

where these drugs were being kept.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. KESEY: Thatâs how.

GROSS: Huh. And then you have friends who were able to make it in their own

laboratories.

Mr. KESEY: Yeah. But it was never was anywhere as good as that good governance

stuff. Thatâs the government, the CIA always has the best stuff.

GROSS: Now you brought up âCuckooâs Nest.â And I was wondering when you were

working in the psychiatric ward, which is what âCuckooâs Nestâ is based on, and

I think you sometimes went in their high on hallucinogenics. Do you think you

ended up writing âCuckooâs Nestâ in a way projecting your experiences as a

quote âsane person high on drugs," projecting those experiences on to people

who maybe had like serious problems?

Mr. KESEY: Well, these people had had serious problem. I mean I saw people

hallucinating and people in bad shape.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. KESEY: Make no mistake about it, being crazy is painful. And being crazy is

hell - whether you get it from taking a drug or whether it happens because

youâre just trying to lead the American way of life and it keeps kicking your

legs off from under you. One way or another, itâs hell on you. And itâs nothing

that's fun about it and I am certainly not recommending it. It is a lens

through which I did stuff, but itâs hard on the eyes. But I think I had a very

valid viewpoint and much closer than a lot of the doctors were having.

At that time, you know, everything was Freudian. If you were messed up it was

because of something that had happened to you when you were in the bathroom as

a kid. And was these experiences â and I don't just mean drug experiences â

there were a lot of other things that were going on that were emphasizing this.

John Coltrane's music was saying the same thing. It was saying something is

wrong and is making us a little crazy and that is making us crazy enough to

hallucinate, whether we were promoting it ourselves or it was being imposed on

us. I donât want to argue that now. But when I would - I felt so good after

being on there all night to know that I was wearing a green uniform and - I

mean a white uniform instead of a green uniform so I could leave in the

morning and go home, otherwise there wasnât that much difference between me and

those people they were locking up.

GROSS: Mm-hmm

Mr. KESEY: It gave me an empathy that I could never have come up with. A better

example is those first few pages of âCuckooâs Nestâ were written on peyote. And

I donât know any Indians. I donât know where the Indian came from. Iâve always

felt humbled by that character. Without the character of that Indian, the book

is a melodrama. You know, itâs a straight battle between McMurphy and the big

nurse. With that Indian's consciousness to filter that through, that makes it

exceptional.

GROSS: Have you given up drugs? Or, I donât know, maybe I shouldnât be asking

this, but do you...

Mr. KESEY: Weâre into it now, go ahead.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Do you still do them at all or?

Mr. KESEY: On religious occasions, yeah.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. KESEY: I like to walk up on a mountain on Easter and get a sense of

rebirth. Some people jog. Some people meditate. You know, thereâs certain

people who whip themselves on the back, there's - everybody has their own way

of trying to see past the veil and this is just the one that I happened to come

up with. My metaphor is this, is that you donât need a huge tuning fork. We

used to think we still have a tuning fork for an eight foot long and weighed

2,000 pounds just to find middle C, but now all you need is a little bitty

tuning fork once a year maybe. But no, I donât know anybody who really goes out

and gets ripped anymore.

GROSS: At what point did you decide to give up the kind of Pranksters life. The

story that Iâve heard is that other Pranksters went to Woodstock. You didnât

want to go. And when they came back, they came back to a sign hung in your

driveway that just said: no.

Mr. KESEY: Well, there were 61 people when they had about to Woodstock. And

after they were gone, I went upstairs - and we live in a barn. We still live in

the same barn. We fixed up and itâs a pretty nice place. But at that time there

was still hay in the loft of the barn. And I found out one of these little

hippie warrens where they dug in with their little ratty old sleeping bags and

their copy of Zap magazine. In stock right down in a hay bale was a candle

which had burned right down to the hay before it had gone off. And I thought

hey, enlightenment is one thing but being this loose is... I mean my grandpa

wouldn't allowed them up there and my great grandpa wouldn't have, and there's

certain things that take precedence over enlightenment.

GROSS: And that's when you sent everybody home, basically.

Mr. KESEY: Yeah.

GROSS: Ken Kesey, I thank you very much for talking with us.

Mr. KESEY: Okay. Take it easy.

BIANCULLI: Ken Kesey speaking with Terry Gross in 1989. He died in 2001.

There's a new documentary about his iconic bus trip using restored footage shot

by Kesey and friends. It's called "Magic Trip: Ken Kesey's Search for a Kool

Place."

Coming up, jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews a new CD released by

vibraphonist Gary Burton.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

139259106

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20110812

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Gary Burton: A New Quartet, A Familiar Sound

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

BIANCULLI: Jazz vibraphonist Gary Burton has been mixing styles since he was a

teenaged prodigy in the early 1960s, recording with Nashville musicians like

guitarist Chet Atkins and Hank Garland. After that, Burton added rock elements

to his jazz in the late 1960s.

Critic Kevin Whitehead says that after that all these years those old

associations still leave a mark.

(Soundbite of song, "Did You Get It?")

KEVIN WHITEHEAD: The blues - "Did You Get It?" - by Antonio Sanchez, the

drummer in Gary Burton's quartet. It's on the album "Common Ground." Burton has

always counted on collaborators to pull him in various directions - not because

the vibist(ph) doesn't have his own preferences, but for the variety. Burton

also likes a tight-knit working band, and he's got one in his new quartet,

which is touring this summer and fall. Sanchez works hand in glove with bassist

Scott Colley; they'd already teamed up in the drummer's band.

(Soundbite of song, "Did You Get It?")

WHITEHEAD: By using four mallets on vibes instead of two, Gary Burton can lay

down bittersweet chords like a piano romantic. But those extra tentacles also

let him do fast octopus dances in complex rhythm, a kind of throwback to '70s

jazz-rock. Burton was there at the dawn of fusion jazz, and that influence

still lurks under the surface.

(Soundbite of song, "Did You Get It?")

WHITEHEAD: The heart of this quartet is the flinty interplay between

contrasting metallic voices: Burton's ringing aluminum vibraphone bars versus

one-time protege Julian Lage's steel-string guitar. His round hollow-body tone

is not so fusion-y, but the tunes the players bring in may involve sudden

wrinkles, knotted lines and shifting rhythms, as in fusion. This is from deep

in Julian Lage's tune "Banksy," where one episode quickly gives way to the next

or jumps back to the last - maybe to evoke the graffiti artist it's named for,

staying one foot ahead of the law.

(Soundbite of song, "Banksy")

WHITEHEAD: For Gary Burton, every new beginning confirms some eternal

constants. In a way he's not so far from where he started, blending with big-

toned country guitarists 50 years ago. "Common Ground" draws other connections

to his past; the one lyrical tune Burton wrote echoes '60s collaborator Carla

Bley, and the quartet revive a poppy Keith Jarrett song Burton played with him

way back when. One reason some things don't change much is they wear well as

they are. Update only as needed.

(Soundbite of song, "Banksy")

BIANCULLI: Kevin Whitehead is the jazz columnist for eMusic.com. He reviewed

"Common Ground" by the new Gary Burton Quartet.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

139534881

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20110812

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Poet Laureate Philip Levine Reads From His 'Work'

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This week, America got a new poet laureate, 83-year-old Philip Levine, an

emeritus professor of English at California State University at Fresno. Best

known for his warmhearted poems about his native Detroit, where he worked in

auto factories as a young man, Levine won a Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for his book

"The Simple Truth." He also won a National Book Award for his collection "What

Work Is" in 1991, which is when Terry Gross interviewed him. She asked him to

describe one of the factories at which he tried to get work.

Mr. PHILLIP LEVINE (Poet Laureate): It's a very exotic place or it was when I

was very young. I mean there was fire. There was noise. There was, it was like

bedlam. Sometimes I remember going into a foundry once to get a job, and I was

about 17 - they wouldn't hire me, I was too young - and thinking, really, I'm

in hell.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. LEVINE: This is like hell. You know, it was so hot and it was this liquid

metal and I was terrified. I was glad they wouldn't hire me.

GROSS: I want you to read the title poem from your new collection "What Work

Is." It is there a story you'd like us to hear about the poem before we hear

the poem itself?

Mr. LEVINE: Yeah, there is. There is a curious story. I never worked at Ford

Highland Park, which I mention in the poem. But I went there once for job

during a period in the early '50s in Detroit when there was a kind of - a

slight recession so a lot of people got laid off, although Detroit was a

booming town back then. And I waited in line and it was raining and it was a

long wait. You know, you - the newspaper would advertise, you know, assemblers.

That's the lowest job you can get. And they would put hours down like 8:00 to

5:00. But you knew you had to be there early if you were going to get a job.

And so you got there at maybe 7:30. Well, they didn't open the employment

office until, say, 9:00, so you stood there for an hour and a half before

anything even opened and there were 50 people ahead of you.

But that was in a way to, you know, they wanted to test you. You know, how much

crap could you take? I mean were you willing to wait in line that long? If you

weren't, they didn't want you. And so I, as I waited I grew angrier and angrier

at myself for being this humble character. And finally, maybe about 10:30 or so

I got up to the head of the line and there was a guy sitting down - I was

standing. We each went to a different desk. We stood. They sat. And he said,

what kind of job would you like? And I don't know where this impulse came from,

but I said: I want your job.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Oh, gee.

Mr. LEVINE: And he said, okay, take off. And that was it. But I was sort of

happy that there was this thing in me that was still there that, you know,

said, you know, I don't want you and you don't want me. Let me read the poem.

"What Work Is." We stand in the rain in a long line, waiting at Ford Highland

Park. For work. You know what work is - if you're old enough to read this, you

know what work is, although you may not do it. Forget you. This is about

waiting, shifting from one foot to another. Feeling the light rain falling like

mist into your hair, blurring your vision until you think you see your own

brother ahead of you, maybe 10 places.

You rub your glasses with your fingers, and of course it's someone else's

brother, narrower across the shoulders than yours but with the same sad slouch,

the grin that does not hide the stubbornness, the sad refusal to give in to

rain, to the hours of wasted waiting, to the knowledge that somewhere ahead a

man is waiting who will say, no, we're not hiring today, for any reason he

wants.

You love your brother. Now suddenly you can hardly stand the love flooding you

for your brother, who's not beside you or behind or ahead because he's home

trying to sleep off a miserable night shift at Cadillac so he can get up before

noon to study his German.

Works eight hours a night so he can sing Wagner, the opera you hate most, the

worst music ever invented. How long has it been since you told him you loved

him, held his wide shoulders, opened your eyes wide and said those words, and

maybe kissed his cheek? You've never done something so simple, so obvious, not

because you're too young or too dumb, not because you're jealous or even mean

or incapable of crying in the presence of another man, no, just because you

don't know what work is.

BIANCULLI: Philip Levine, during a conversation with Terry Gross in 1991. This

week he was appointed the country's next poet laureate.

(Soundbite of music)

BIANCULLI: You can join us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter at nprfreshair.

And you can download podcasts of our show at freshair.npr.org.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

139575421

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.