Onion Editors Regroup Following Sept. 11

Shortly after the attacks of Sept. 11, Onion editor Rob Siegel and writer Todd Hanson produced two issues of the paper which featured articles including "U.S. Urges Bin Laden to Form Nation It Can Attack," and "Security Beefed up at Cedar Rapids Public Library."

Guests

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on October 4, 2001

Transcript

DATE October 4, 2001 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Harry Shearer on comedy after the September 11 terrorist

attacks

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

On the opening of last week's "Saturday Night Live," Lorne Michaels asked Rudy

Giuliani, `Is it OK to be funny?' It's a question a lot of comics have asked

themselves. Today we'll talk with several satirists about going back to work

after September 11th.

Harry Shearer doesn't pull his punches, whether his subject is politics, media

or showbiz. You can hear his satirical sketches and commentary on his

nationally broadcast public radio program "Le Show." He's a former "Saturday

Night Live" writer and cast member, and a co-creator and star of the film

"This is Spinal Tap." On the "Simpsons" he's the voice of Mr. Burns,

Smithers, Ned Flanders and other characters. Harry Shearer lives in LA, but

on September 11th he was in Australia. Here's a sketch from last week's

edition of "Le Show." As usual, Harry does the music and voices, including the

voice of Larry King.

(Soundbite of "Le Show" with Harry Shearer providing voices)

"Mr. LARRY KING": We're back. And just to remind you again, coming up on

Tuesday, the president of Egypt, Hosni Mubarak, and the great Vic Demone. Now

we've been closing our shows with a song, an inspirational moment or two. And

today we welcome back, in our Los Angeles studio, the former lead singer of

the hugely successful boy band Boys R Us, Dewey Gordon. Dewey, good to see

you again. Last time you were here you had a song about Elian Gonzalez.

"Mr. DEWEY GORDON:" That's right, Larry. "Let Elian Stay" was the tune.

"Mr. KING": Yeah. Uh-huh.

"Mr. GORDON": And while, of course, it didn't succeed in keeping young Elian

Gonzalez in this country, it sure did succeed in moving a lot of units.

"Mr. KING": Yeah. Well, you're here to sing a new song tonight, Dewey, just

being released as a single.

"Mr. GORDON": Yes, sir, Mr. King. It's called "Where's Your Flag?" You know,

I feel very strongly that, as a former member of a very successful so-called

boy band, a term, by the way, that I'm very proud of...

"Mr. KING": Yeah.

"Mr. GORDON": ...that I have an obligation not only to help out the

firefighters and the rescue workers in New York...

"Mr. KING": They're getting the proceeds of this record?

"Mr. GORDON": Better yet, Larry, they're getting a hundred thousand free copies

of the record.

"Mr. KING": Yeah.

"Mr. GORDON": But I also have an obligation, you know, to show the American

people that Dewey Gordon is a serious artist with something serious to say,

something that I hope helps to heal old divisions as well as create some new

ones.

"Mr. KING": OK. We've just got a minute left, Dewey.

"Mr. GORDON": OK. Well, I just want to say, Larry, that this song is straight

from my heart, not that every other song I've done hasn't been as well, but,

you know...

"Mr. KING": Even more from the heart.

"Mr. GORDON": That's right.

"Mr. KING": Dewey Gordon.

(Soundbite of "Where's Your Flag?")

"Mr. GORDON": (Singing) Oh, your shelves, they're stocked with goodies, but

being in the store is such a drag 'cause the red, white and blue is nowhere in

view. Hey, where's your flag? Yeah, your hotel, though so very charming, and

you know I really hate to nag, but there's going to be hissin' Old Glory is

missin'. Hey, where's your flag? Where's your flag? Doesn't sit in your

window, doesn't fly from your roof. Hmm-mm. Where's your flag? You say you

love your country, but how about your proof? Oh, it could be a banner or

poster. It could be a pin, a decal or a coaster. But before I buy tires or a

toaster, where's your flag? Where's your flag?

GROSS: That's a sketch from Harry Shearer's public radio program "Le Show."

Harry, welcome back to FRESH AIR. Many comics have felt kind of lost since

September 11th...

Mr. HARRY SHEARER (Host, "Le Show"): Yeah.

GROSS: ...feeling like it's inappropriate to be funny, particularly when the

whole nation is grieving, and then feeling lost that there's nothing to be

funny about right now. What was it like for you to get back to work as a

satirist?

Mr. SHEARER: Well, the first show I did was from Melbourne, Australia, and

that was about the most challenging thing I've ever done. Because when you're

doing this kind of work, what's my zone of confidence is my feeling that I'm

swimming in the same medium as my audience. And now, all of a sudden, being

12,000 miles away, having seen the TV--you know, having seen Dan Rather on the

air and all of the rest--still, I wasn't in the same emotional world as my

audience. And it was the most difficult show I've done, just to try to figure

out, `How am I going to pitch this?' Pitch in a musical sense, not in a show

business sense--`How am I going to pitch this that's appropriate?'

So I basically decided to do the show. There was no prepared comedy in it,

and I basically took all the "show," quote/unquote, elements out of it and

basically just talked for an hour. It was in the middle of the night in

Melbourne, Australia, anyway, so it was basically more of like a campfire talk

with a friend than a show.

And then the next week, I just got back on. You know, my first thought was,

`George W. Bush, you know, is doing, I think, certainly compared to the

expectations of a lot his detractors, a pretty amazing job now. And he must

be sitting there thinking, "This is great, and yet Rudy Giuliani's getting so

much better press than I am."' So I wrote a sketch about that, you know, and

I thought, `There's no way around the fact that he's probably feeling that,

and that's human comedy. There's nothing wrong with that.'

I had second thoughts about one joke that I put in there. He's having a

telephone conversation with his dad. I do this series of 43 and 41 phone

conversations, much like they do. And I had George W. Bush saying, you know,

early on (mimicking George W. Bush), `You know, I've never been so determined

and so focused since the fourth time I quit drinking.' And I thought about

that joke for a minute, and I thought, `Well, that's really on the edge.' But

it made me laugh, and I thought, `Ah, he might well say that. You know, that

might well be true, and it might well be what's in his mind.' So I let it go,

and I didn't receive a single complaint about it. So I'm glad I...

GROSS: But it sounds like you're maybe sorry that you included it?

Mr. SHEARER: No. No. I'm just citing that as the most different from my

normal mode of conduct--is I actually second-guessed a joke.

GROSS: Right. I guess that is different for you.

Mr. SHEARER: Yeah.

GROSS: I think a lot of comics are thinking of the president as being kind of

off limits now.

Mr. SHEARER: Yeah.

GROSS: They don't want to criticize our leadership at a time when our

security is genuinely at stake.

Mr. SHEARER: Yeah. Well...

GROSS: What are your thoughts on that?

Mr. SHEARER: ...clearly one might be approaching this in a slightly different

manner. We've seen that the journalistic consortium, which was doing a very

painstaking recount of the Florida vote, has decided not to make its results

public at this time because they don't think it's appropriate to even open the

door to questioning the president's legitimacy at this time. So, you know,

I'm way inside those boundaries. But, you know, this is a time when the basic

role of humor and topical comedy becomes what Freud said it was, which is to

laugh at what makes us scared.

GROSS: So what are some of the things that make you scared that you've been

laughing at?

Mr. SHEARER: Well, you know, the idea that Jesse Jackson was going to inject

himself into this situation again, and there was some talk about Mike Wallace

wanting to go along with him. And, you know, what I've been talking about a

lot on the show is this mantra we've been hearing now: `Everything has

changed.' As a matter of fact, there's an LA radio station that uses that as

their slogan now: `Everything has changed, KFI Los Angeles.' Of course,

their call letters haven't changed, but--and so much hasn't changed. And we'd

like to believe we live in a time when everything has changed.

I said on my first broadcast back, you know, people go to the Elvis Presley

vigil at Graceland on the anniversary of his death, or they go to some

ball game that has some special significance. And when you ask them why they

go there, they always say, `Well, I wanted to be part of history.' Well, now

we know what it feels like to be part of history, and it's not the greatest

thing in the world. But in terms of everything changing, a lot hasn't changed

and a lot doesn't change because human nature doesn't change. We like to

believe that we live in a country that, I think for both political and

religious reasons, likes to believe that history comes to screeching halts.

So part of, you know, my job is just to poke fun at the things that don't

change. The Mike Wallace-Jesse Jackson conversation that I had was basically

about two ego-driven guys trying to very gently negotiate their way to figure

out how they could do this thing and not, you know, go over the line. And I

think there's a lot of that going on. So, you know--and one might find that

scary, or one might find that reassuring, but I definitely find that something

to laugh at.

GROSS: My guest is actor and satirist Harry Shearer. We'll talk more after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is actor and satirist Harry Shearer. You can hear his

political satire on his nationally broadcast public radio program "Le Show"

and on his Web site, harryshearer.com.

Now I want to get back to President Bush. I mean, you have been very

comfortable satirizing President Bush in the past. Are there things that

you're not comfortable taking on now, areas in which you might still strongly

disagree with him, but you feel like, `Well, now's not the time to do a sketch

about that'?

Mr. SHEARER: I don't know. Because I do the show by myself and I don't have

meetings with myself, I haven't...

GROSS: You don't have a policy yet.

Mr. SHEARER: Yeah, I haven't written myself a memo on this subject. It's the

sort of thing where it only will occur to me when an idea occurs to me, and

either I'll reject it out of hand because I think it's not right or I won't.

But I haven't had such an idea yet, so I don't know what it might be. I mean,

to me, the line is really a very bright line. There's nothing funny and no

humor to be found in the disaster itself, in the tragedy that affected so many

lives. That's so far off limits it's not even worth discussing.

But, you know, as with--and this is a trivial comparison, but it serves to

make the point--when one was making a great deal of fun of the circus that

surrounded the O.J. Simpson trial, there was nothing funny about the crime

that started the whole thing off. That was horrific and terrible, and nothing

funny could be done about it. But as the thing wound on and we learned more

about these characters and their very human foibles, to put it mildly, there

was a great deal of fun to be had with that.

And I feel the same way about this. You know, I go back to, you know, my

experience with being on the air during the Gulf War, which is the closest

analogue to this in many ways. And, you know, when people's lives are on the

line, I wasn't making fun of the strategic decisions and the troop movements

and the battle orders that were being given because that's serious stuff, and

that's, you know, national security and you don't make fun of that, especially

at that moment.

But, you know, the Pentagon's eagerness to release the videotape showing, you

know, how smart the bombs were already smelled to me like show business at the

time, and it, of course, turned out to be, in the same way that, you know, in

the wake of this, it was obvious to me that banning curbside check-in was show

business. It wasn't security, and I called it that. You know, there's a

certain amount of security that we have in this country that really is show

business; that, basically, they are just to make people feel good, but it

serves no other function. And so, you know, there's something amusing to me

about pointing out that even in the most serious circumstances, a lot of what

we are presented with is just more show business, like we don't have enough of

that.

GROSS: White House Press Secretary Ari Fleischer said something about having

to be careful what we say.

Mr. SHEARER: And what we do. `Watch what you say, watch what you do.' This

was his response to the Bill Maher incident, and he prefaced quite candidly,

I thought, by saying he hadn't seen the transcript of Bill Maher's remarks

yet. So without the proper amount of information at hand, Ari Fleischer felt

no compunction about going ahead and saying, `The message is watch what you

say, watch what you do,' which I think is a little more disturbing than

anything out of Bill Maher's mouth.

GROSS: What did Bill Maher say?

Mr. SHEARER: Bill Maher had Dinesh D'Souza on his show, and Dinesh D'Souza

said, you know, something to the effect of--and I don't have--I'm like Ari

Fleisher. I don't have the transcript here, but I've read it. Dinesh D'Souza

said something on the lines of, you know, `It's a mistake to call these

terrorists cowards.' And Bill Maher picked up on that and said, `Yeah. You

know, cowardly is dropping cruise missiles from 2,000 feet up,' which is a

point that was made, I think, days before by Susan Sontag in The New Yorker.

But The New Yorker doesn't depend on Sears for ads, and a shock jock in Texas

raised a ruckus: `Can you believe this guy said American soldiers are

cowards?' And pretty soon we saw, as they were always asking us to, the

softer side of Sears.

GROSS: Did you ever wish that you could almost be like Bob Hope and feel like

you were really, like, through your comedy, boosting the morale of the United

States by entertaining the troops? Do you know what I mean? Just feeling

like--I'm sure Bob Hope was always able to feel that his comedy was really

helping serve the war effort; that he was doing something really tangible.

Mr. SHEARER: Yeah. Well, it also kept him away from home. You know, I must

say, Terry, I've gotten--and it's only because you ask me that question will I

indulge in this kind of self-serving response. But I've been really pretty

moved by the e-mail response that I've gotten since the shows have followed in

the wake of the attacks, because there's been an emotional quality to the

response. They've all been positive, but there's been an emotional quality to

the response that says that some availability of a voice that's not in

lockstep with the major mainstream media's sense of what's appropriate at the

moment, which includes Dan Rather going on "David Letterman" and crying as he

recites the third stanza of "America the Beautiful" and saying, in response to

David Letterman's question, `Well, what's going on here?'--Dan's full response

was, `They hate us.'

You know, somebody who pokes a few holes at that, I think, I don't want to

make, you know, exaggerated claims for it, but people say that it serves some

value to them. And, you know, if it's still on Armed Forces Radio, maybe it

serves some value for our men and women in uniform.

GROSS: Harry, what media have you been watching?

Mr. SHEARER: All the cable news outlets, BBC news, both radio and television,

the three major networks, NPR, reading some of the British papers, the

Australian papers. You know, one thing that's really been interesting this

period of time--and this will take some old-timers back, but if you're like me,

your e-mail `in' box has almost been like a teach-in. There have been a

remarkable number of e-mail dispatches that I've gotten from people who have

been in the Army in Afghanistan during the time that we were helping Osama bin

Laden during his Freedom Fighter phase. Remember that? And people who are

expert in chemical and biological--you know, there has been an amazing amount

of information flowing, along with the Nostradamus predictions and all of the

rest of the hoaxes.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SHEARER: So I've been, you know, sort of immersing myself in that.

GROSS: Any impressions you want to share about what else it's like to be in

Hollywood now? I know you're about to tape the "Bob Patterson" show, the new

Jason Alexander comedy.

Mr. SHEARER: Yeah.

GROSS: Just what's the atmosphere like now?

Mr. SHEARER: Well, you know, on the surface, it seems pretty normal. We did

a "Simpsons" yesterday, and it had the--basically, usual vibe to it. You

know, there's a lot of sort of joking with a bit of fear underneath the

surface about this security tighten-up that's going on at these studios. I

think it's done to reassure people, but I think, paradoxically, it brings fear

more into that place than it might otherwise be.

You know, there's just this ambient fear level that's going around. I don't

know if you know this story, but last week in Los Angeles, there was an

evacuation of a subway station because a couple of policemen went, `What's

that smell?'--which, apparently, we don't know the answer to that question

yet, but it apparently was some cleaning solvent or something. But that's the

kind of mass hysteria that we're teetering on the brink of, and I dare say

that no matter how sophisticated a terrorist apparatus is, they don't know

that we have a subway in Los Angeles. So, you know, it would be so far down

the list.

So, you know, I think part of the job of humor, at this point, is to try to

defuse this potential for that kind of behavior, you know, because, you know,

mainstream journalism, I think, did a really good job in the first week or

two--pretty good job in the first week or two after the attacks. But now

they're reverting--you know, they're reminding us that what they were doing

before the attacks, the business they were in, was the, `10 things in your

kitchen that could kill you. Details at 5.' That's the business they were

in, and they're still in that business. They just have, you know, meatier

stuff to play with. So, you know, to me, it's important to kind of make

people laugh at some of this, because otherwise they're going to freak out.

GROSS: Well, Harry, I want to thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. SHEARER: Thanks, Terry. My pleasure.

GROSS: Harry Shearer's political satire can be heard on his public radio

program "Le Show" and on his Web site, harryshearer.com. I'm Terry Gross, and

this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

(Credits)

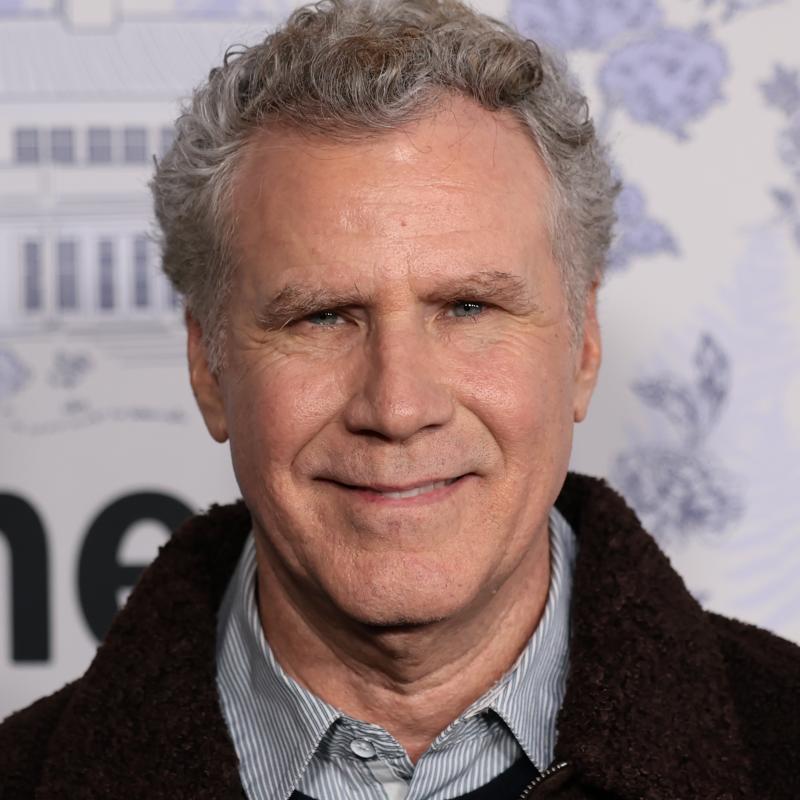

GROSS: Coming up, Will Ferrell of "Saturday Night Live" on rethinking his

impersonation of President Bush. Also, highlights of the last two editions of

the satirical newspaper The Onion. We talk with editor Robert Siegel and

writer Todd Hanson. And David Bianculli reviews last night's special episode

of "The West Wing" about tensions in the White House after September 11th.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Will Ferrell on changing his comedy sketches after the

September 11th terrorist attacks

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Last week, on the season's first new edition of "Saturday Night Live,"

producer Lorne Michaels asked Rudy Giuliani if it's OK to be funny. After a

somber opening, the cast returned to humorous sketches, but the sketches

avoided the terrorist attacks and their aftermath. And Will Ferrell did not

do his impersonation of President Bush. He says he plans to do a Bush sketch

this weekend. We called Will Ferrell earlier today.

Will, lots of the jokes, when you do Bush, have been about him not being very

bright...

Mr. WILL FERRELL ("Saturday Night Live"): Right.

GROSS: ...and very kind of frat boy. Are you going to think that's

appropriate or inappropriate now?

Mr. FERRELL: Well, I mean, so much of our approach is, in a way, taking what

the perception is and then turning it back around and, you know, regurgitating

it to the audience. And, obviously, we don't think that is so much the

perception anymore, so it'll probably be changed somewhat. I know the piece

this week actually is more of a take-charge Bush and kind of playing more off

of that. So, I mean, at least initially, that might be the new angle.

GROSS: Has September 11th made you think differently about satire than you

ever thought before, about what the function of it is, what the bounds of

taste are?

Mr. FERRELL: Yeah, it really has. Last night was our read-through night,

where we read through all the sketches that have been written, and there's the

first cut, if you will, of what's going to be done. And usually a group of us

go out and grab a bite to eat, and we ran into one of the writers on "Conan

O'Brien" because they're in the same building, and we kind of just had this

shared discussion of checking in with each other, like, `How are you guys

doing?'--and back and forth. And there was--pretty much, the topic of

conversation was how slowly kind of getting back to work, trying to kind of

get back into the swing of things, and at times feeling like you're getting it

back; like you're feeling like you're being able to come up with funny stuff,

and yet, at least at this point, it's still kind of flavored with this thing

of sitting at your computer saying to yourself, `Is this, ultimately, really

that funny? Is anything still that funny?' And that's been the hardest thing

to kind of fight through.

GROSS: Now you're in the new movie "Zoolander," which is a spy comedy.

Mr. FERRELL: Right.

GROSS: It's set in New York, and there are skyline scenes. And the World

Trade Center has been, I guess, digitally erased from the scenes.

Mr. FERRELL: Right.

GROSS: I assume it's digitally.

Mr. FERRELL: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: How do you feel about that? Do you think that was the right choice to

take it out?

Mr. FERRELL: You know, I went and saw it last Sunday with an audience here in

Manhattan, and I noticed those skyline shots, and Ben Stiller had, in fact,

told me that he had to go back and kind of lift those out. And, you know, at

first my reaction was like, `Oh, of course. That's the right thing to do.'

And then I wondered, as I watched it, what would have been the reaction from

the audience had those buildings been left in. Would it have been, you know,

an audible gasp, or would it have been more of an homage to those, you know,

tall skyscrapers?

GROSS: Are you performing at the Carnegie Hall comedy benefit Monday, and if

so, what are you going to do?

Mr. FERRELL: Yes, I am. And I'm still trying to think of that. Jerry

Seinfeld was nice enough to call me to ask me to be, like, the emcee of the

evening, and he pretty much, you know, prefaced it by saying, `You can be

funny or you don't have to be,' or whatever. So you know what? I'm kind of

just leaving that up to the last minute in terms of what I'm going to do or

say. You know, I'm not a stand-up comic, so I don't usually get up there and

do the, `Hey, how's everyone doing?' type of shtick. So I'll probably think

of a few things that I'll try; otherwise, it's probably not my job so much to

be hilarious as it is to just kind of greet people and say hello and get the

show going, you know.

GROSS: Any chance you'll do it in persona as President Bush?

Mr. FERRELL: No--well, I was trying to think if there was any Bush material I

could do, but probably not. I may try to sing at some point as Robert Goulet.

GROSS: Oh, that's always good.

Mr. FERRELL: So that's always good.

GROSS: That's always a good thing.

Mr. FERRELL: You can always go to that.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. FERRELL: Yeah.

GROSS: What song do you think would be appropriate?

Mr. FERRELL: "What Kind of Fool Am I," I don't know. That would be nice

maybe.

GROSS: Well, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. FERRELL: Gosh, thank you.

GROSS: And good luck this weekend on "Saturday Night Live."

Mr. FERRELL: OK.

GROSS: And good luck Monday.

Mr. FERRELL: Thanks, Terry.

GROSS: Will Ferrell is a cast member of "Saturday Night Live," and he

co-stars in the new movie "Zoolander."

Coming up, the editor in chief and head writer of the satirical newspaper The

Onion. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Robert Siegel and Todd Hansen on articles appearing

in The Onion

TERRY GROSS, host:

The satirical newspaper The Onion has put out two editions dealing with life

after September 11th. Headlines have included: `US Urges bin Laden To Form

Nation It Can Attack,' `American Life Turns Into Bad Jerry Bruckheimer Movie'

and `President Urges Calm, Restraint Among Nation's Ballad Singers.' The

Onion is published online at theonion.com. It's also sold at newsstands.

Their pre-September 11th work is collected in a new book called "Dispatches

from the Tenth Circle." I spoke with editor in chief Robert Siegel and head

writer Todd Hansen. Here's Siegel reading a News In Brief item that he wrote.

Mr. ROBERT SIEGEL (Editor In Chief, The Onion): The headline is: `Bush Sr.

Apologizes To Son For Funding bin Laden in '80s.' Midland, Texas: `Former

President George Bush issued an apology to his son Monday for advocating the

CIA's mid-'80s funding of Osama bin Laden, who at the time was resisting the

Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Quote, "I'm sorry, son," Bush told President

George W. Bush. "We thought it was a good idea at the time because he was

part of a group fighting communism in Central Asia. We called them, quote,

`Freedom Fighters' back then. I know it sounds weird. You sort of had to be

there." Bush is still deliberating over whether to tell his son about the

whole supporting Saddam Hussein against Iran thing.'

GROSS: What was it like for you at The Onion to get your bearings after the

attack and to figure out how you wanted to respond as a publication?

Mr. TODD HANSEN (Head Writer, The Onion): Well, to be honest, it was almost

impossible to do that. We made the decision immediately that we weren't going

to go ahead and publish an issue that week. None of us, as comedy writers,

had anything funny to say. I think many comedy writers have had the same

response. Then in discussing what we should do when we came back the

following week, there were many, many hours of discussion that went into

deciding what to do. And I think when it started, we were all sort of

agreeing--not agreeing, but assuming that we would do material that was not

related to the news; that was not topical and that would be just something

that wouldn't touch on it. I think most people have had that same reaction.

That seems to be what most of the other comedy sources have done.

However, even though that was our initial assumption, we then realized that

the more we talked about it, it became more and more obvious that we wanted to

make some sort of response because it seemed like any other material would be

kind of irrelevant. So by the time we were done with those discussions, we

had arrived at the conclusion that we would do something to respond to the

events of September 11th. So it was a scary situation to be in, but it seemed

like it was the only thing we could do.

GROSS: One of the targets of your satire in The Onion is the hijackers'

beliefs. And I'd like you, Robert, to read: `Hijackers Surprised To Find

Selves In Hell.'

Mr. SIEGEL: OK. `The hijackers who carried out the September 11th attacks on

the World Trade Center and Pentagon expressed confusion and surprise Monday to

find themselves in the lowest plain of Nar, Islam's hell. Quote, "I was

promised I would spend eternity in paradise, being fed honeyed cakes by 67

virgins in a tree-lined garden if only I would fly the airplane into one of

the twin towers," said Mohamed Atta, one of the hijackers of American Airlines

Flight 11, between attempts to vomit up the wasps, hornets and live coals

infesting his stomach. "But instead I'm being fed the boiling feces of

traders by malicious, laughing Ifrit. Is this to be my reward for destroying

the enemies of my faith?'

GROSS: Robert, what was the editing process for that? Maybe you could tell

us who came up with it. And, you know, when it passed your desk, were you

comfortable with it right away? Was there any considerations you had before

publishing it?

Mr. SIEGEL: Well, the idea was mine, so I was comfortable with it. I looked

at it as one of the rare opportunities in this whole thing to actually take a

traditional, nasty Onion-style shot at someone, and I didn't expect that we'd

be flooded--I didn't think our switchboards would be flooded by people

outraged that we were...

Mr. HANSEN: Showing disrespect to the hijackers.

Mr. SIEGEL: ...fictionally torturing the hijackers. It seemed like a great

opportunity to do our more traditional--one of the types of humor we do, but

the type of humor that we felt we could not do in this issue. So I felt

pretty good about it, and I felt like it was--you know, I wanted a broad range

of things in this issue, of styles of humor and broad range of subjects, to

try to capture the whole thing. And there were a lot of very sentimental

articles in the issue, and this was one where it was sort of meant to be a

crowd-pleaser in that it was, you know, the kind of thing that people could

sort of--cheer is the wrong word, but, you know...

Mr. HANSEN: It was a cathartic moment, I think, for us to just deal with the

rage.

GROSS: Robert, another piece I'd like to ask you to read--and this one is

headlined: `Dinty Moore Breaks Long Silence On Terrorism With Full-Page Ad.'

I think this is one you came up with.

Mr. SIEGEL: Yeah.

GROSS: Tell us about the inspiration for it and then maybe read the piece for

us.

Mr. SIEGEL: The inspiration is pretty simple. It's just, even still, every

day since the attacks, you've seen full-page ads in USA Today and The New York

Times from every single company in America, you know, expressing their

sympathy and support for the victims of this tragedy and speaking out against

terrorism, condemning the attacks. And, in some cases, we're not really--I

mean, are we, as a nation, really wondering how, you know, a particular

company really feels about these attacks? I would assume that everyone feels

sympathy and support for the victims and condemns terrorism.

`Dinty Moore Breaks Long Silence On Terrorism With Full-Page Ad'; New York:

`Nearly two weeks after the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon,

the makers of Dinty Moore beef stew finally weighed in on the tragedy Monday

with a full-page ad in USA Today. Quote, "We at Dinty Moore extend our

deepest sympathies to all who have been affected by the terrible events of

September 11th, 2001," read the ad, which pictured a can of Dinty Moore beef

stew at the bottom of the page. "The entire Dinty Moore family is outraged by

this heinous crime and stand firmly behind our leaders." Dinty Moore joins

Kanoki Heating & Cooling(ph) and Tri-State Jacuzzi(ph) in condemning

terrorism.'

You know, and it's sort of along the same lines as, you know, Rosie O'Donnell

donating a million dollars and then, you know, sending out a big press release

announcing that she has donated a million dollars. I mean, if you want to

donate a million dollars, donate a million dollars, but, you know, you don't

need to take credit for it and show the world how good--you know, what a good

person you are. So it just feels like they take advantage, to some extent.

So...

GROSS: Well...

Mr. HANSON: But I also think that part of the humor in the piece that Rob

just read is not so much attacking the hypocrisy of Dinty Moore or the

fictionalized version of Dinty Moore in that story as it is...

Mr. SIEGEL: And we have nothing against Dinty Moore specifically.

Mr. HANSON: Yeah--as it is also just reflecting the sense of helplessness

that everybody feels...

Mr. SIEGEL: Help--yeah.

Mr. HANSON: ...you know, because you don't know what to do. So you take out

an ad and, like, `We, the makers of Dinty Moore beef stew, condemn terrorism.'

It's like, well, it's kind of a futile gesture, but I think everyone can

relate to it. It's not necessarily an unsympathetic thing either because...

Mr. SIEGEL: No.

Mr. HANSON: ...I think everyone can relate to that feeling of like, `Well, I

don't know what to do,' you know.

GROSS: Yeah, yeah. Exactly, exactly. Robert, I'm wondering about some of

the ideas that you rejected because you thought that the tone was wrong or it

was inappropriate in some way, that you found it offensive in some way or just

wasn't working.

Mr. SIEGEL: Well, we rejected a lot. The headlines that really would have

been wrong headed and truly offensive, we didn't even come up with. I think

we all--before we started brainstorming our ideas, we talked about what our

basic take on this should be, and we all really agreed that we should, to some

extent, sacrifice jokes for the bigger picture, the larger message. So there

weren't even, really, that many jokes pitched that were just way, way off base

in terms of offensiveness or target. There were a lot that sort of towed the

line; that just to be absolutely sure, we would cut. I don't know. Todd, do

you think I should give examples or just...

Mr. HANSON: Well, it's hard to do that.

Mr. SIEGEL: The Quadragon? I don't know.

Mr. HANSON: Yeah. Well, all right, I'll say one that almost got on was--the

intent behind the joke was, again, to be something to reflect the way everyone

felt so helpless, and the headline was: `America Stronger Than Ever, Say

Quadragon Officials.' And...

GROSS: Oh, gosh. Right.

Mr. SIEGEL: Instead of the Pentagon...

GROSS: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Mr. HANSON: Yeah, instead of the Pentagon, it was--and we thought it was

funny and sad, but then as soon as we had actually written it up on the board

to select, you know, we're like, `No, we cannot use that because people are

going to think we're having a laugh at the expense of the people in the

Pentagon,' which we would never, ever want to do and would never even think

of, you know.

Mr. SIEGEL: It just does more harm than good. So...

Mr. HANSON: And then we realized, you know, `Even though that's not what we

mean by the joke, we don't know if other people take it that way.' And even

still, you know, there are some people who have taken the jokes that we did do

the wrong way. I mean, just because since it's satire, no one ever knows how

sarcastic you're being or what you're being sarcastic about. So it's a very

risky thing.

GROSS: You have a new book called "Dispatches from the Tenth Circle: The

Best of The Onion." And this is the second collection of pieces from The

Onion, and there's one piece in this book, at least one piece that I noticed,

that certainly relates to terrorism, and I'm curious how you feel about it

now. The headline is: `Terrorist Extremely Annoyed By Delayed Flight.' The

dateline is Chicago: `His flight from O'Hare to La Guardia delayed more than

six hours, Hamas militant and would-be suicide bomber Nidal Hanani vowed

Friday never again to fly United Airlines. Quote, "I do not have time for

this," said Hanani, seated at a Burger King in concourse C, a plastic

explosives-filled duffel bag at his feet. "My jihad against the West was

supposed to be carried out shortly after takeoff at 8:35 this morning. It is

now 2:50 PM. How much longer must I sit around this airport like an idiot

before God's will is done?"'

How do you feel about that one now?

Mr. SIEGEL: Well, it's something we definitely would not have run in a

post-September 11th issue, but I don't feel the need to apologize for it,

seeing as it was written two years ago.

Mr. HANSON: I mean, the question of appropriateness in satire always comes

down to what the target of the satire is. In that case, the target of the

satire is, I think...

GROSS: The airlines.

Mr. HANSON: Well, no--is all of the articles...

Mr. SIEGEL: Air traveler.

Mr. HANSON: ...about business travelers and how terribly inconvenienced they

are.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. HANSON: And it's contrasting the sort of trite and mundane frustrations

of, `Ahh, I've been sitting in an airport for three hours,' with, you know,

the life and death, you know, horribleness of a suicide bomber. And, I mean,

it's not even really about terrorism as much as it's about just people

complaining, business travelers complaining about airport inconvenience.

GROSS: I wonder if you have any observations you want to share about how

other comics and satirists who you've been paying attention to are dealing

with this.

Mr. HANSON: Well, I think it's pretty obvious that when the White House

press secretary says that Bill Maher should watch what he says, that there's a

pretty blatant irony there in that, you know, they're saying, `This is a time

when freedom is under attack and under threat. You know, there's a threat to

our freedoms, so, therefore, at this time, you know, watch what you say.'

Mr. SIEGEL: Let's tear up the Constitution.

Mr. HANSON: I mean, we live in a free country, and if we want to defend our

free country against those who hate our free country, then we should remember

that Bill Maher has a right to say whatever he wants.

GROSS: Well, I want to thank you both very much for talking with us.

Mr. SIEGEL: Thank you very much.

Mr. HANSON: Thank you.

GROSS: Robert Siegel is the editor in chief of the satirical newspaper The

Onion. Todd Hansen is the head writer. The Onion is published online at

theonion.com. A new "Best of The Onion" book has been published called

"Dispatches from the Tenth Circle."

Coming up, TV critic David Bianculli on last night's special episode of "The

West Wing." This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Episode of "The West Wing" dealing with terrorism

TERRY GROSS, host:

Last night NBC's "The West Wing" presented a special episode written and

produced with unusual speed in reaction to last month's terrorist attacks. TV

critic David Bianculli has this review.

(Soundbite of song)

Unidentified Singer: There's something happening here. What it is ain't

exactly clear.

DAVID BIANCULLI reporting:

Last night's episode of "The West Wing" ended with that classic '60s protest

song by Buffalo Springfield. It was an appropriate choice, and not only

because of the confusion, anger and warning in the lyrics. Stephen Stills

wrote that song and recorded it with his band only a few weeks after clashes

between youngsters and the Los Angeles Police Department erupted into riots in

1966. It was a case of an artist feeling so deeply about what was happening

around him that he wanted, maybe needed, to react instantly in the language

and medium he knew best.

Not too long afterward, another group in which he was a member--Crosby,

Stills, Nash and Young--did the same thing. Within three weeks of the Kent

State shootings in 1970, where four students were shot and killed by the

National Guard, that influential rock group had written and recorded an angry

song called "Ohio."

Aaron Sorkin, writer-producer of "The West Wing," had the clout and platform

at NBC to move with similar speed. He wanted to talk about terrorism, its

roots and its impact, and came up with a method to do it. But he's a

scriptwriter, not a songwriter. Instead of writing lyrics for a three-minute

song, Sorkin wrote a script for a one-hour drama series and had his characters

explain all the things Sorkin wanted to say.

A lengthy preface, delivered by the series' actors as themselves rather than

in character, explained the special show's premise. It was a stand-alone

episode, not part of the regular "West Wing" story line or time line. It

imagined a time, in our near-distant future, when security lockdowns of the

White House occurred on an almost weekly basis. Last night's show began with

one such security breech, triggered just as Bradley Whitford as Josh is about

to reluctantly address a group of bright, young, visiting high school

students.

The lock-down confines Josh and the students in the same room. Slowly, over

the course of the hour, all the other "West Wing" characters, including Martin

Sheen as the president, wander in to calm the students and take questions on

terrorism; all the characters, that is, but John Spencer's Leo, who is

conducting an impromptu and fairly hostile interrogation of a White House

staffer who is of Middle Eastern descent. A recently arrested terrorist had

named several colleagues, one of whom went by many aliases; one of those names

was the same as that of the White House staffer, so Leo feared there was a

mole and perhaps a potential assassin deep within the White House.

Logistically, this very focused pair of plots allowed Sorkin to confine his

action almost completely to two sets and to make the points he most wanted to

make. With the interrogation scenes, where the worker turned out to be

accused unjustly, there was the smell of a witch-hunt and a warning about

prejudice. And with the student scenes, Sorkin was able to import a classroom

into the West Wing, so that all the other staffers could take turns lecturing.

But that was the problem with last night's show. It was, at bottom, close to

an hour-long lecture. Ordinarily, I'd say that's great. There are millions

of people, especially young people, for whom a dramatic summary of the issues

of terrorism would be a service as well as an hour of thought-provoking

entertainment. But anyone who watches "The West Wing" regularly is

politically aware anyway, and if a young person doesn't care much about "The

West Wing," a special episode devoted to terrorism isn't likely to be a big

draw.

So the show last night, in a very literal sense, was preaching to the

converted, and some of the preaching was very familiar, especially the parts

echoing a well-circulated letter on the Internet in which Afghanistan was

compared to Poland and the Taliban to the Nazis and Islamic extremists to the

Ku Klux Klan.

Sorkin, in the past, has admitted to using things he read on the Internet, and

that certainly looks like it happened again here. That doesn't mean the show

didn't have resonance. At the end, when Josh entertained one final question

from a student, he answered with a response that was more emotional than

political.

(Soundbite from "The West Wing")

Unidentified Actress: Can I ask one more question?

Mr. BRADLEY WHITFORD: (As Josh) Yeah.

Unidentified Actress: Do you favor the death penalty?

Mr. WHITFORD: (As Josh) No.

Unidentified Actress: But you think we should kill these people?

Mr. WHITFORD: (As Josh) You don't have the choices in a war that you do in a

jury room, but I wish you didn't have to. I think death is too simple.

Unidentified Actor: What would you do instead?

Mr. WHITFORD: (As Josh) I'd put them in a small cell and make them watch

home movies of the birthdays and baptisms and weddings of every single person

they killed over and over every day for the rest of their lives. And then

they'd get punched in the mouth every night at bedtime by a different person

every night. There'd be a long list of volunteers. It's all right. We'll

wait. But, listen, don't worry about all this right now. We've got you

covered. Worry about school. Worry about what you're going to tell your

parents when you break curfew. You're going to meet guys. You're going to

meet girls. Not so much you, Ralph. Learn things. Be good to each other.

Read the newspapers, go to the movies, go to a party, read a book.

In the meantime, remember pluralism. You want to get these people? I mean,

you really want to reach in and kill them where they live? Keep accepting

more than one idea. It makes them absolutely crazy.

BIANCULLI: The important thing, in this case, I think, isn't that last

night's episode was one of the finest dramatic hours of "The West Wing." It

wasn't. The important thing is that Sorkin tried and had a place to do it.

Think for a minute about how few places in prime time there are that could

make room for such an attempt. Think of how few shows have any real

relevance, and think of how few shows week in and week out say anything

provocative or meaningful. So thank "The West Wing" for trying and for being

there at all.

GROSS: David Bianculli is TV critic for the New York Daily News.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.