Contributor

Related Topic

Other segments from the episode on September 28, 2018

Transcript

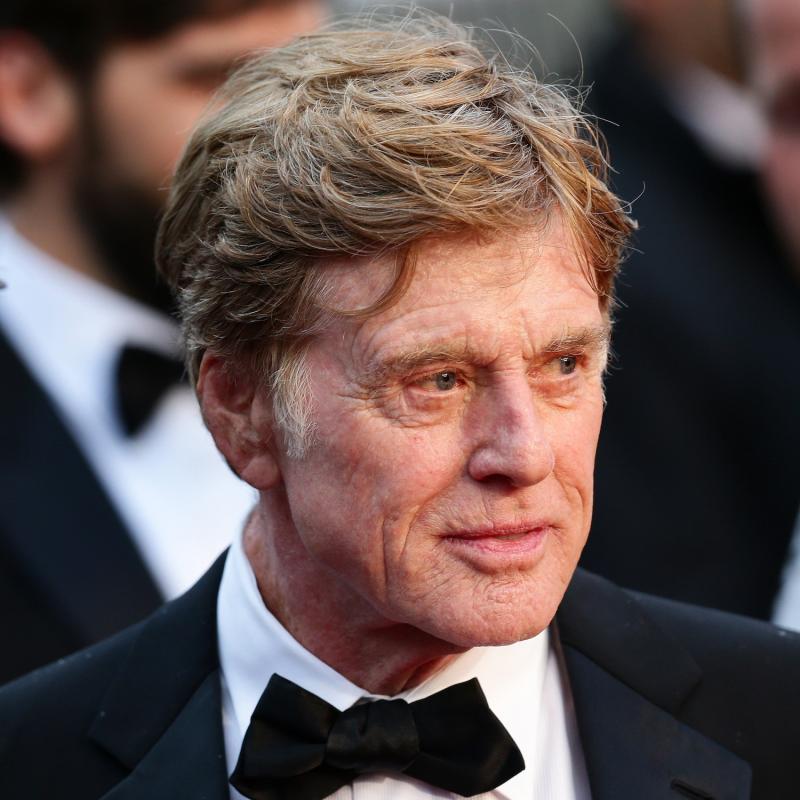

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Robert Redford has said that his new film, "The Old Man & The Gun" would be his final film performance. And then he said he shouldn't have said that. Nevertheless, we're going to take this opportunity to look back on his early years, his childhood and his early acting career. In the new film he plays a man who looks quite dignified and gentlemanly, and has robbed banks all his life, done prison time and broken out of prison. In this scene, after starting a romantic relationship with a woman played by Sissy Spacek, he tells her about his profession and she doesn't believe it.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "THE OLD MAN & THE GUN")

ROBERT REDFORD: (As Forrest Tucker) So what'd be worse, if I'm lying about this or telling you the truth?

SISSY SPACEK: (As Jewel) Prove it.

REDFORD: (As Forrest Tucker) Prove it?

SPACEK: (As Jewel) Yeah.

REDFORD: (As Forrest Tucker) You want me to prove it?

SPACEK: (As Jewel) Yeah.

REDFORD: (As Forrest Tucker) Well, what do you do if I can't?

SPACEK: (As Jewel) I will walk out that door.

REDFORD: (As Forrest Tucker) No, I'm not going to do it.

SPACEK: (As Jewel) I didn't think so.

REDFORD: (As Forrest Tucker) Not because I can't - because it's just not my style.

SPACEK: (As Jewel) Not your style. You have style?

REDFORD: (As Forrest Tucker) I do.

SPACEK: (As Jewel) Well, tell me what that is then.

REDFORD: (As Forrest Tucker) My style?

SPACEK: (As Jewel) Yeah.

REDFORD: (As Forrest Tucker) OK, well, let's take this place. This place is not my style. Say it was a bank. And say that that camera up there, that was really a teller's window and that lady standing there was the teller behind the window. And you'd just walk in real calm, and you'd find yourself a spot and you sit down, just like we're sitting here. And you wait. And you watch. And that may take a couple of hours, might take a couple of days even, but you wait. It's got to feel right, the timing has to feel right. And when it does feel right, you make your move. So you walk right up, look her in the eye and you say, ma'am, this is a robbery. And you show her the gun like this.

GROSS: My most recent interview with Robert Redford was in 2013, after the release of his film "All Is Lost" in which he was the only character. New York Times film critic A.O. Scott called it the performance of a lifetime. When we spoke, before talking about his past, we talked about "All Is Lost." He played a man alone on a small yacht in the Indian Ocean. Early in the film, a stray shipping container rams into the yacht, leaving a hole. When a storm hits his life is in jeopardy but he has to remain calm and resourceful. It was an incredibly physically demanding role. There's no dialogue in the film, just voiceover. Here's Redford in the beginning of the film reading a letter he's writing. We don't know who he's writing to.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "ALL IS LOST")

REDFORD: (As Our Man, reading) 13 of July, 4:50 P.M.

I'm sorry. I know that means little at this point, but I am. I tried. I think you would all agree that I tried - to be true, to be strong, to be kind, to love, to be right. But I wasn't. And I know you knew this in each of your ways, and I am sorry. All is lost here, except for soul and body - that is, what's left of them - and a half days ration.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: Robert Redford, welcome back to FRESH AIR. That's such a stirring opening for the beginning of the film. You read that letter as if it were a poem. Did you want to know your character's backstory, like who he's talking to? You assume it's family. You don't really know anything about who he's writing to, what his life has been like, why he's out in this yacht in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Did you have to know this yourself?

REDFORD: In the beginning, I thought I needed to ask questions to the director, J.C. Chandor. But frankly, Terry, I was very drawn to what you did not know about this. I was very drawn to what was not said. There were challenges in there that were very attractive to me. One of them was that I saw the project because there was only a 30-page script, and it was mostly sketches since there's no dialogue. I was attracted to the fact that there was no dialogue. I liked the idea there were no special effects. It was a very low-budget film, very independent in its spirit and its budget. And because I felt that it was more of a pure cinematic experience the way films used to be, maybe even going back to silent films.

High technology has kind of entered the film business, maybe infested the film business. But going to what you're saying, I think, yes, I did ask in the beginning, is there something I should know about this? And the director evaded answering it, and then I realized that this is what was intended. And so I went with that, I liked - yes, I could fill it into a certain degree but not too much beyond.

GROSS: So the director said, referring to the reaction he expected you to have when first reading this script, he said, Redford's either going to say hell yes, this sounds amazing or he's going to say, why in the world would I do that? I have nothing to prove. Why would I put myself through that? And you really do put yourself through a lot in the movie. I mean, you're being pelted by water through much of it. I mean, your yacht is flooded, so, like, you're wading in water. I know you shot some of this in a tank and not in the ocean, but some of it was, I believe, shot in the ocean. So you're out...

REDFORD: Yes.

GROSS: ...In the ocean under the hot sun. You're in storms. I mean, it seems like it was a grueling shoot. Give us a sense of some of the things that you had to endure. Like, when you're in the storm, in one of the storms and, you know, you're being rained on, what are you experiencing? How are you protecting yourself?

REDFORD: Well, it was a real - first of all, it was a real storm because the, yes, as you say, a lot of it was on the open water. But when we had to get into the really tough stuff, we went into a giant tank where they had these big wave machines, these big cylinders that can cork up the waves to 6, 7 feet that will swamp the boat or maybe turn it over. You had rain, violent rain machines. Then you had wind machines. And you had crew members with fire hoses hitting you with water, heavy streams of water.

So when all of those things are cooking at once, you really are in a storm. So I really did feel, while I was doing this, that I was actually in a storm. And I had to feel like I needed to feel, like I'm really in a storm, what am I going to do? How am I going to - and it became very physical. I also went into this, I guess at my age, wondering, what can I still do? I always - because I was in sports as a kid and, you know, I was athletic pretty much my life, I wanted to - I always enjoyed doing my own stunts when I could.

And I thought, well, at this point in my life, what can I still do? I'm not sure, so it was, in a way, a test. I said, well, let's see what I can do, you know, and I'll do what I can. And then you push yourself and your ego kicks into gear. And you say, well, maybe I should really - let me do this. And, of course, when I did that, J.C.'s ego kicked in. He said, yeah, let's push the guy. So we were pushing each other, I guess.

GROSS: Now, I read that during some of the filming, because of all the water that was attacking you, you got an ear infection and I think temporarily lost hearing, 60 percent of your hearing in one ear. Is that accurate?

REDFORD: Yeah, yeah it is.

GROSS: Is it temporary?

REDFORD: I wish it was. It's sort of permanent.

GROSS: So I hate to put it this way, but if you had it to do over again, would you have saved your hearing and said no to the film?

REDFORD: No, no. The hearing thing isn't that bad. And I would have done what I did. I would have done it all over again. I would be happy to do it again. I may not be able to, but I would be happy to try.

GROSS: You know, when the credits roll, it says cast, Robert Redford - and that's it.

REDFORD: It's embarrassing.

GROSS: You are the cast. And then after that, there's this like long scroll of, you know, camera people and effects people and the people who dealt with the fishes and the people on the ships. And I'm thinking, like, this is a huge group of people working on the film, and you're like the only person ever on camera. That must have been such an odd position.

REDFORD: When I saw that - you know, I've only seen the film once.

GROSS: I'm surprised you saw it. Don't you sometimes not even see your films?

REDFORD: Sometimes, yes. Sometimes, I've not seen - some films I've not seen.

GROSS: But anyway, you were saying.

REDFORD: That's a whole other story. But anyway - when - the first and only time I saw it was at the Cannes Film Festival. And so when the film - because, you know, they boo films there.

GROSS: Yes.

REDFORD: And so when the lights came down, I'm thinking, geez, this could go either way. And I'm sitting here in a tux. How embarrassing to be in a tuxedo and be booed. You know, so I'm sitting there thinking, God, I wonder how this is going to go. So then I saw the screen - cast member, just me alone. And I thought, oh, my, am I really - I'm really in trouble now if they boo at this thing because they're going to be booing me, you know. Anyway, it went the other way. Happily, it went so much the other way. That, in itself, was a shock, a pleasant one.

GROSS: You know, a couple of years ago, there was a biography of you written by Michael Feeney Callan. And I was reading that and was really surprised to learn that, as a child, you had polio. I mean, you're such a physical person. You're so athletic and so physically fit. You needed to be in order to do "All Is Lost." And the thought of you being paralyzed for a while as a child was shocking to me.

REDFORD: Yeah, it was to me, too (laughter).

GROSS: Sure.

REDFORD: It wasn't a severe case. I think we should - you know, I want to make sure we get this straight. It wasn't an iron lung case. It was a case of mild polio, but it was severe enough to put me in bed for two weeks. And because in those days, polio, before the Salk vaccine was discovered, what hung over your childhood was always the fear of polio because all you saw were people in iron lungs. So yeah, when I got it, it was because of an extreme exertion in the ocean - in this bright sunlight in the ocean. And it was alarming, but it wasn't serious enough to go much further.

GROSS: Were you paralyzed at all?

REDFORD: No, no. I was down. I was - I couldn't move very well, but I was not paralyzed.

GROSS: And - tell me if I'm getting too personal here - so soon after you had the polio, your mother gave birth to twins who died shortly after birth. I'm just thinking that's a lot of trauma at one time.

REDFORD: Yeah, I guess it depends on how you're raised and what your genealogy is. You know, family - you come from maybe a dark - more of a dark family - immigrated from Ireland and Scotland and didn't talk much, didn't complain - you don't complain much. You don't ask for anything. You bear the brunt of whatever comes your way, and you do it with grace. So when my mom had twin girls that died, there was no talk about it.

And that goes all the way back to when I was a little kid, when I was very close to my uncle, who was in the Second World War. And he was with General Patton's Third Army. He was an interpreter because he spoke four languages fluently. And so I was very fond of him, and he would - on his furlough, he'd come down to play baseball with me and so forth.

Then he went away to war, and he was killed in the Battle of the Bulge. But when he died, I was very close to him. The way the family dealt with it was it just wasn't talked about. It just happened, and you didn't ask a lot of questions. You just - it was what it was. And so I think that was sort of built into a family structure. So as a result, when my mom went through that, there was no talk about it. Everybody moved on.

GROSS: Your mother died when you were 18. She was sick. I'm not sure what she died of. How did that change the course of your life? Did you have to, like, rewrite your plans?

REDFORD: Well, I don't know that it changed anything at the time. She was a wonderful person. She died very young. She was full of life, full of laughter, full of love. She was out there. I mean, she would take chances, and she was very risky. And she taught me how to drive a car when I was 10, and nobody knew about it. I mean, that kind of stuff. So we had a close relationship, but also, I was of a young mind, just like all the other kids my age were. You didn't want your parents around. You didn't want your parents doting on you. You didn't want attention or anything like that. And you had a mother that wanted to give you that attention, and you kind of pushed it away. I feel bad about that.

GROSS: You went to college. And from what I've read, academics was not your thing so much and that you did a lot of drinking and rode motorcycles...

REDFORD: Yes.

GROSS: ...Or drag races...

REDFORD: Yes, yeah - the whole thing.

GROSS: ...Or whatever.

REDFORD: The whole thing.

GROSS: Right.

REDFORD: Well, not - I don't know about that because that came a little bit later. It was really - I went to college to get out of Los Angeles. I went to college because it was Colorado, and it was the mountains. And I - by that time, I realized that nature was going to be a huge part of my life, that Los Angeles for me was a city that, when I was a little kid at the end of the Second World War, I loved that - I loved it. It was full of green spaces.

And suddenly, when the war ended and the economy revived, suddenly Los Angeles had no land use plan. It felt like the city was being pushed into the sea that I love because suddenly there were skyscrapers and freeways and smog. And I said, wait a minute - what's - I wanted out. So I went into the mountains into the Sierras and worked at Yosemite National Park and fell in love with nature that way. And I realized that nature was going to be a big part of my life. So I sought land elsewhere that I thought would be kept free of development.

GROSS: You talking about Sundance?

REDFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: We're listening to my 2013 interview with Robert Redford, recorded after the release of his film "All Is Lost." He stars in the new film "The Old Man & The Gun." We'll hear more of the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF AMANDA GARDIER'S "FJORD")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my 2013 interview with Robert Redford.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: So not long after shooting "Butch Cassidy," you cofounded a new organization called Education Youth and Recreation to promote alternative films on university campuses. This was really...

REDFORD: Yeah, that was a big mistake.

GROSS: It was a big mistake? Why was it a big mistake?

REDFORD: Well, because at that time, I was already beginning to feel the urge to do something that would be maybe more supporting more independent-type films. The idea was that we would get some funding together and that we would buy up films that had been either poorly distributed like Billy Friedkin's "Birthday Party" or "Dynamite Chicken" - you know, some of the documentaries because I always love documentaries. I was always extremely positive and supportive of documentaries - and so whatever I could do to promote them, even back then in 1970.

We thought, well, what if we buy up documentaries that were either not distributed or poorly distributed and films that were the same, put them into a package and went for the college market, went right to the colleges and say, OK, we're bringing this to you? Well, what we realized - that no one came - that we assumed that there was a college market. But no - what most of the students wanted to do was to go into town to see "Doctor Zhivago." So there were just very few that wanted to see films like this. They were kind of film buffs, but that wasn't enough to create a college market. So it failed.

GROSS: Did you lose money personally on that?

REDFORD: No. I didn't have my own money into it, but I suspect that over time, if I look back on it, that was probably the...

GROSS: The roots of Sundance?

REDFORD: ...The genesis of what later became - so yeah.

GROSS: It's interesting that back in - what? - the late '60s, early '70s you were already thinking in those - in that direction.

REDFORD: Yeah. And it was different then because, you know, one of the beauties was that I was able to work in both - within the mainstream. In those days, the studios would allow for smaller films to be made under their umbrella. So if I had - like, I wanted to tell stories about the America that I grew up in. And for me, I was not interested in the red, white, and blue part of America. I was interested in the gray part that - where complexity lies and where things get complicated. But I wanted to tell stories about issues that were American like - that had impact on people, like politics and sport and business.

And so I got two of them made. And I wanted to make them like documentaries. So one was "The Candidate," the other was "Downhill Racer" about a ski racer. But in those days, you would do a larger film, but you would also be able to - if you did those films, you could say, well, would you allow me to make this smaller film? And they would do it. So "The Candidate" and "Downhill Racer" were done at Warner Brothers. At the same time, I would do a larger Warner Brothers film like "All The President's Men" or what have you. So that carried through the '80s until the business changed.

Then suddenly, Hollywood became more centralized. It was following the youth market. Technology was creating more chances for special effects, which would be more of a draw for the youth. And so Hollywood, which basically - Hollywood follows the money. That's what it does. And so it was going that direction. And it was beginning to leave behind those other kinds of films. And so there was this gap there. They weren't likely to be making those films anymore. They were going to be offloading them.

That led to the idea of, well, to keep this thing alive - because this is where new voices are going to be developing or new films can be coming that are independent that are more exciting and more humanistic and stuff like that. So that was what led to the idea of Sundance, first with the labs and then the festival. But if I look back on it and think back in time, probably started way back then with that first venture that failed.

GROSS: Well, yeah, it was interesting. Taking the films to college campuses failed, so you started on your own campus, and people would come to you.

REDFORD: (Laughter) For a guy that never graduated from anything, that's pretty interesting.

GROSS: Do you try to see a lot of the films that come out of Sundance?

REDFORD: I try to, yeah. I sometimes don't get to see all of them. It's been a little - in the beginning, it was more fun. It's not quite the fun anymore it was when it was just starting 'cause you're uphill. You're kind of against the odds. And there's something exciting about that risk. And you're pushing it and pushing it. There's something exciting about it. And then once success comes, then suddenly other elements come into it that kind of load it all up. And then you find yourself doing, like, publicity or interviews or having to meet this top person or that top person. And all that's right. That's proper I guess. But it's not the fun it was when you were standing out there trying to get people in like you were standing outside of a strip joint, you know, and say, hey, you want to come in and see this movie?

GROSS: Listening back to my 2013 interview with Robert Redford, who stars in the new film "The Old Man & The Gun." After a break, we'll talk about his childhood, his early acting career on episodic TV shows and the film that made him a star, "Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid." I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my 2013 interview with Robert Redford. He stars in the new film "The Old Man & The Gun." We're looking back on his early years when he got his start as an actor.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: You did a lot of episodic TV early in your career in the early 1960s - "Maverick," "Rescue 8," "The Deputy," "Playhouse 90," "Perry Mason," "Naked City," "The Twilight Zone"...

REDFORD: Hey, now Terry - Perry Mason - Now, look...

GROSS: (Laughter).

REDFORD: Do you know what the title of that - that was what, 1959? You know what the title of that was?

GROSS: What?

REDFORD: "The Case Of The Treacherous Toupee."

GROSS: (Laughter).

REDFORD: That was the name of it. I was so excited to have a job, you know?

GROSS: Wait; who had the toupee? Was it - wasn't you, right?

REDFORD: I couldn't remember now. It wasn't Raymond Burr. But somebody did, some blond - but those were your apprenticeship years. And it's always - one of the things that's sort of been weird is to see yourself characterized so often as somebody that looks - well, that has glamorous looks or is appealing physically. That's nice. I mean, I'm not unhappy about that. But what I saw happening over time was that was getting the attention. And sometime - because I always felt that I was an actor. And that's how I started. I wanted - I was a person who loved the idea of craft and that learning your craft was something fundamentally and good. And I wanted to be good at my craft. And therefore, I would be an actor that would play many different kinds of roles, which I did. I played killers. I played rapists, really deranged characters. But most people don't know about that because that was in television.

So suddenly you're seeing yourself kind of in a glamour category, and you're saying, well, wait a minute. You know, the notion is that, well, you're not so much of an actor. You're just somebody that looks well. And that was always hard for me because I always took pride in whatever role I was playing. I would be that character. Like, you know, if you look at, say, "Jeremiah Johnson" - you know, the character in the wilderness. And within the same year, I was doing "The Candidate." And you put those two together, and you would hope that somebody would say, well, somebody is acting here.

GROSS: I wanted to play a clip from your early episodic TV years and was thinking, well, I'm a big fan of "Route 66." I have the box set.

REDFORD: Oh, really?

GROSS: Oh, yeah, I love that show. I loved it as a kid, and I love it looking back at it.

REDFORD: As a kid - thanks a lot. What were you - 10? - when I did my segment?

GROSS: Hey, I was alive then. A lot of people weren't.

(LAUGHTER)

REDFORD: What I liked about "Route 66" was not so much the show as it was the route because I remember hitchhiking as a kid back and forth on Route 66 because there were no freeways then. There were no turnpikes or anything like that. And so Route 66 was the way you got from Chicago to LA or vice versa.

GROSS: So anyway, so I figured, whoa, let's do a clip from "Route 66." And then I'm reading your biography, and I read this line on page 87 - and that you're saying to your agent, I'd rather rot than be remembered for "Route 66" (laughter).

REDFORD: I said that?

GROSS: You're quoted as saying that. What can I say?

REDFORD: Am I? I can't remember the show. Do you have a clip, you say?

GROSS: Yeah, yeah. So this is - you don't even remember doing it? - this is from a 1961 episode with Nehemiah Persoff as your father. And it's set in a mill town in a Polish-American community. And, like, you've gone off to out-of-town college, so you've gotten out of the mill town. But you're back on a college break. And the episode opens with you chasing after your girlfriend, who's running away in the woods. And you're not trying to attack her or anything. You're just trying to catch up to her and to reach her and to communicate with her.

She accidentally kind of falls off this hill and hits her head and dies. You don't know what to do. So you don't call the cops. You don't tell anybody. You try to tell your father, but your father just doesn't want to hear anything. You're having trouble communicating with him. He doesn't want to hear it. Later, the police discover her dead. You're implicated in her death. So here's you trying to explain to your father, played by Nehemiah Persoff, what was really going on with your girlfriend and what was really going on with your relationship with your father.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "ROUTE 66")

REDFORD: (As Janosh) Do you know why she ran - because she said to me, do you love me? Will you marry me? And I couldn't answer her with the truth. I couldn't say, yes, oh, boy, I want to marry you. Before God and the whole world, I do. How can I say that to her and hurt her even more? I wanted to marry her. Would you have stood for it, papa?

NEHEMIAH PERSOFF: (As Jack) If you had to marry her...

REDFORD: (As Janosh) No, I didn't have to. It was never anything like that.

PERSOFF: (As Jack) Then why should I have allowed you? Why you not come to me? Why you not come to me?

REDFORD: (As Janosh) Have I ever, ever, ever been able to come to you, papa, with anything that was my own idea? Haven't you always decided everything for me? Haven't you decided everything for me always - who I am must be, what I must be, how I must be?

I don't remember that at all. I'm not ashamed of it obviously. But I don't - God, that's so interesting. I don't remember - I just don't remember that at all. That's amazing.

GROSS: So your voice sounds, you know, so much different. It's higher.

REDFORD: Well, yeah, I was recently - J.C. and I - J.C. Chandor and I were at a festival.

GROSS: The director of "All Is Lost," yeah.

REDFORD: Director of "All Is Lost" - J.C and I were at a festival, and they ran clips of my career that I had never seen. They had clips going all the way back all the way up to now. And it was very uncomfortable, very uncomfortable. And I did the last "Playhouse 90" that was ever done. I just thought that was the best show. When I was a kid, I thought that was the best show on television. And I was fortunate enough to be in the very last "Playhouse 90" that was written by Rod Serling. And I was able to be - I played a young German lieutenant - a very sympathetic Nazi lieutenant. He gets corrupted by - or somebody else tries to corrupt him, but he resists the corruption. And Charles Laughton played the rabbi.

GROSS: Oh, acting with Charles Laughton must have been so interesting. But there's a great story that's told in your biography about the slap.

REDFORD: Oh, yeah, he was intimidating. It was one of my first parts. And there was a scene with George MacCready, who played my commanding officer. And it's during a pogrom, and they're calling out names in the street to be packed into trucks. And then after, we come up to the rabbi's apartment. And there's a tension between the rabbi, played by Charles Laughton, and MacCready. And there's a intellectual challenging involving Nietzsche and God and so forth. So I'm just there clueless. I'm this young, innocent, naive guy. And at one point, Laughton drops something. He drops his Bible. And I reached down to pick it up, which is a no-no.

And MacCready sees this and realizes, uh-oh, this kid needs some training. And the rabbi sees that my instinct is to be compassionate. I reached down to pick up the Bible. And so he looks me in the eye. And the look is like, I see who you really are. I see who you really are. MacCready says, apparently you feel like you have to be sympathetic to the rabbi. Hey says, therefore, I instruct you to slap him. So then I supposedly slap him - I am reluctantly, but I slap him.

As we were getting ready to do it - it was going to be live. It was going to be live telecast. As we're getting ready in rehearsal, Laughton comes up, and he says, dear boy, you can't give me the slap. What are you going to do? And I said, what do you mean what am I going to - he said, what are you going to do because I can't be hit. I said, you can't be hit? No, I can't be hit. What are you going to do? And I thought, oh, jeez, now what am I going to do, you know? So I go to the director, and I said, what am I supposed to do here? And he said, oh, gee, don't bother me. I've got enough troubles.

So we get on the show, and I'm sitting there. As we're getting to the moment, I'm thinking, who is this guy to tell me what I'm supposed to - what I can't do, what I can do? And I got so riled up, and I was so nervous on top of it that when it came time, I thought, who's he to tell me what I can do or can't do? So I hauled up and really whacked him. And it wasn't a slap. It was a whack. And his jaw - spit came out of his jaw. You know, and he looked at me, and tears came out of his eyes. He looked at me. And when it was over, I thought, oh, boy, you know, I'm going to get a mouthful. So I go to his dressing room to apologize. I'm really sorry. He says, no, you did the right thing. You did the right thing.

GROSS: That's such a great story. And it's so interesting that you have such a vivid memory of doing that "Playhouse 90" edition and of the Charles Laughton story and no memory of "Route 66" (laughter).

REDFORD: Well, I think it's because "Playhouse 90" was such a big deal as a kid. There were two shows on television - the "Sid Caesar Show" - I forgot the name of it...

GROSS: "Your Show Of Shows"?

REDFORD: "Show Of Shows," yeah. And it would come to Los Angeles via kinescope I think. And "Playhouse 90" - those two shows were the top of the line on drama and comedy. And it made a huge impact on me as a kid. You know, I just thought they were wonderful shows. And the idea that I could be in one and particularly since it was going to be the last one - it was a big honor. It was a real thrill for me.

GROSS: We're listening back to my 2013 interview with Robert Redford, who stars in the new film "The Old Man & The Gun." We'll hear more of the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my 2013 interview with Robert Redford. We've been talking about how he got started acting.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: So skipping ahead to 1969, you make "Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid" with Paul Newman. And this is the movie that makes you kind of iconic. Had you - did you already know how to ride horses? Did you like Westerns when you were making this?

REDFORD: Yeah. Yeah, I knew how to ride horses. I loved horses. I liked doing my own stunts when I could. When it first came up, because of the age difference between Paul and I, which was like 12, 13 years - and he was really well-known. I was not well-known. I had just done I think the film "Barefoot In The Park." But he had a career obviously that was very high. And so the studio did not want me. The director, George Roy Hill, and I met in a bar on Third Avenue.

And they were putting me up to play Butch Cassidy because I'd done this comedy on Broadway so - you know, nobody thinks very deep about stuff like that. They said, well, if he did a comedy, maybe he should go up for Butch Cassidy. And so we're sitting in this bar. And I told him at the time - I said, yeah, I can do that, but that's not the part that interests me. The - I'm more interested in the Sundance Kid. I feel more comfortable in that role. I feel more - I could connect more to that character. And that surprised George. And then he got kind of sold on that idea.

But the studio didn't want me. And they tried everything to keep me out of the film at that time. It was 20th Century Fox. And I think it was Paul Newman and William Goldman, the writer, and George that stood up for me against the studio. But the one that really pushed to the side of course was Paul. And when I met Paul, he was very generous. And he said, I'll do it with Redford. I never forgot that. That was a gesture that I never forgot. I felt that I really owed him after that. And then he and I in the course of that film became really, really good friends. And that friendship carried on to the next film, and then it carried on into our personal lives.

GROSS: He was originally supposed to be the Sundance Kid, and you were supposed to be Butch Cassidy.

REDFORD: Yeah, that's right. The original title of the script was "The Sundance Kid And Butch Cassidy." That was the original title that Goldman had written. And Newman was to play Sundance. But he had played that kind of part before. And George was a guy that saw Paul - he saw a side of Paul that many hadn't seen because he had worked with him on television and he knew him personally. He says, no, this guy - he's very nervous. He talks light, tells bad jokes. He - I think I see him as Butch Cassidy. And he saw me as Sundance. So he had to fight for that. So when it was finally done, then they changed the title to "Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid."

GROSS: Would you mind if I played a scene?

REDFORD: Mmm mmm.

GROSS: OK. So this is kind of a famous scene where, you know, you're both bank and train robbers. And at this point, you're not exactly surrounded, but you're cornered. You're on...

REDFORD: A ledge.

GROSS: A ledge, yeah. And on top of you on this, you know, rocky ledge is the posse that's hunting you down. You got no place to turn. You've got no place to go except for the water that's underneath. And that's - you're up really, really high, and it's a very rocky...

REDFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: ...River or stream. But anyways, as Butch Cassidy is trying to figure out what their options are, what you want to do is, like, shoot your way out. And so you speak first.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID")

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) Ready?

PAUL NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) No, we'll jump.

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) Like hell we will.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) No, it'll be OK if the water's deep enough and we don't get squished to death. They'll never follow us.

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) How do you know?

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) Would you make a jump like that if you didn't have to?

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) I have to, and I'm not going to.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) Well, we got to, otherwise we're dead. They're just going to have to go back down the same way they come. Come on.

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) Just one clear shot - that's all I want.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) Come on.

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) Uh-uh.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) We got to.

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) Nope. Get away from me.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) Why?

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) I want to fight them.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) They'll kill us.

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) Maybe.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) You want to die?

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) Do you?

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) All right, I'll jump first.

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) Nope.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) Then you jump first.

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) No, I said.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy) What's the matter with you?

REDFORD: (As the Sundance Kid) I can't swim.

NEWMAN: (As Butch Cassidy, laughter) Why, you crazy, the fall will probably kill you.

GROSS: How reassuring.

(LAUGHTER)

REDFORD: Yeah, right.

GROSS: So that's my guest, Robert Redford, with Paul Newman from the 1969 film "Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid." Were you surprised at how famous that scene became?

REDFORD: Yes, I was. I mean, that - I was surprised at the whole thing. I remember when I saw the rough cut - I mean, I loved making the film. I had a lot of fun. I've never had so much fun on a film as I have that one. But when I saw the rough cut of it, I said, wait a minute; what's that song doing in it?

GROSS: Oh, "Raindrops Are Falling On My Head," the background song.

REDFORD: Yeah. I said, wait a minute; what's that all about? I said, what in the hell? I said, raindrop - first of all, it's not raining. Secondly, what's that got to do with anything? I thought, well, that - they're - this killed the film.

GROSS: (Laughter).

REDFORD: It made no sense to me. You know, how wrong can you be? I had to listen to that song on the radio for six months.

GROSS: (Laughter).

REDFORD: But the film - also, Terry, another thing that's interesting about how - I guess the value of word of mouth. I remember when the film came out, George Roy Hill and William Goldman were very upset and depressed because the reviews were mixed to negative. And word of mouth is what made the film build. But when it first opened, it had these mixed reviews. I didn't read them. I remember they were very upset and depressed.

And one of the reasons the reviews - some of the reviews were negative was that - the anachronism of the dialogue, like modern-day talk then. I found that pretty inspiring and fun. It was just fun. But apparently, that - that's what some of the negative response was. But it was - I guess - overridden by the acceptance of the whole film.

GROSS: By the way, I had the same reaction about "Raindrops Are Falling On My Head" in the middle of the film. I thought...

REDFORD: (Laughter) Did you really?

GROSS: Yeah. (Laughter) I mean, it made absolutely no sense to me.

REDFORD: Well, it's you and me, then. There's two of us.

GROSS: (Laughter) Well, unfortunately, our time is up. It's really been a pleasure to talk with you. Thank you so much for coming back to FRESH AIR.

REDFORD: Well, thank you, Terry.

GROSS: It's been such a pleasure.

REDFORD: Yeah. And your voice is a lot more pleasant than mine.

GROSS: Oh, I wish (laughter).

REDFORD: No, it is. You have a beautiful voice.

GROSS: (Laughter) I wish. Oh, thank you so much. (Laughter) I'll play that back in my mind.

REDFORD: (Laughter) OK.

GROSS: I actually occasionally do that. That was Robert Redford, recorded in 2013. His new film is called "The Old Man And The Gun." This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. The new film "Monsters And Men" tells the stories of three Brooklyn men, played by Anthony Ramos, John David Washington and Kelvin Harrison Jr., whose lives are impacted by the shooting of an unarmed black man by a white police officer in their neighborhood. The movie won a Special Jury Prize at this year's Sundance Film Festival for Reinaldo Marcus Green making his feature writing and directing debut. Film critic Justin Chang has this review.

JUSTIN CHANG, BYLINE: The opening scene of the haunting new drama "Monsters And Men" immediately sets a mood of slow-building tension and silent outrage. An African-American man named Dennis played by John David Washington is driving around New York, singing along to Al Green on the radio. A white police officer pulls him over and asks to see his license. Dennis quietly complies and also shows his badge. He's a cop too. The interaction ends without further incident, but the damage is done. As Dennis will later note, this isn't the first time he's been pulled over by a cop for the crime of driving while black.

What we are watching is just a prologue, an introduction to a trilogy of stories set in Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. The writer and director, Reinaldo Marcus Green, has structured "Monsters And Men" as a daisy chain of loosely connected narratives. We will return to Dennis later. But first, we meet Manny, a young Latino man played by Anthony Ramos of "Hamilton" fame. He has a wife, a young daughter and a job working security at a sleek Manhattan office building.

But everything changes when Manny witnesses a black man named Darius, or Big D, being confronted by police on a street corner in Bed-Stuy one night. Manny whips out his cellphone and records the incident, which ends with Big D getting fatally shot. The police will later erroneously claim that the victim was lunging for an officer's weapon. But Manny's video footage, which he posts online, reveals a different story. Manny's brave actions reap some unpleasant personal consequences.

But before we can see them play out, the movie whisks us back to Dennis, the cop we met earlier. He too is unnerved by the shooting in his precinct and also by the anger of black friends and neighbors who suddenly regard him as an enemy rather than an ally. Washington recently played a cop torn between his racial identity and his professional duty in Spike Lee's "BlacKkKlansman." But his work in "Monsters And Men" is quietly superior, a seething slow burn of a performance.

Before long, the story shifts focus once more, now settling on a black high school student named Zyrick, played by Kelvin Harrison Jr. Zyrick is a smart, shy kid who normally keeps his head down and who's close to securing a college baseball scholarship. But he's rattled by the heightened police presence in his neighborhood, especially after he's stopped and frisked by cops while walking home one night. Zyrick begins attending protests against the warnings of his father, played by Rob Morgan, who just wants him to focus on baseball.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "MONSTERS AND MEN")

ROB MORGAN: (As Will Morris) Hey, Zyric, where you think you're going?

KELVIN HARRISON JR.: (As Zyric) I'm going downtown.

MORGAN: (As Will Morris) Downtown?

HARRISON: (As Zyric) I mean, can't see you what's happening out there?

MORGAN: (As Will Morris) And you want to do what exactly?

HARRISON: (As Zyric) I thought you'd...

MORGAN: (As Will Morris) Thought I'd what?

HARRISON: (As Zyric) I'd thought you'd understand.

MORGAN: (As Will Morris) This happens every day, man. You better start listening to what's going on around you.

HARRISON: (As Zyric) But I am listening.

MORGAN: (As Will Morris) Z, I mean, you've got a hoodie on for Christ's sake. Come on, Z. You're going out at night to some damn march on the night before the biggest day of your life, son. some. Work with me, man. Cities are going to keep burning. Kids are going to keep getting shot. And cops are going to keep getting off. And I don't like that neither, son, but I know it's a reality, all right. But my reality right now is that you have a ticket out.

CHANG: The echoes of real-world headlines are unmistakable and in some cases deliberate. Big D was inspired by Eric Garner, the Staten Island man who died in 2014 after being placed in a chokehold by police. Another plot point clearly references the shooting deaths of two New York police officers from later that year. But there's more to "Monsters And Men" than it's carefully engineered topical parallels. Green has made a politically urgent, emotionally layered portrait of how a single violent act can send tendrils of shock, anger and anxiety outward into a vulnerable community. There are a few on-the-nose scenes when the script runs the risk of stuffing talking points into its characters' mouths. But the power of the movie lies in its silences - those moments when it shows its characters thinking, reflecting and then taking quick decisive action.

The cinematographer Patrick Scola keeps the camera in motion - sometimes trailing the characters from behind, sometimes framing them from across a street or a park. The movie is somehow both meditative and propulsive - pushing and pulling the characters toward moments of moral clarity. Notably, Green doesn't show us the video of Big D's shooting almost as if he were unwilling to sensationalize his own narrative. Instead, he shows us Manny, Dennis and Zyric all watching the video in private. And in their expressions, we can see rage, grief and a helplessness verging on paralysis.

But if "Monsters And Men" begins in despair, it moves slowly but surely toward a note of bracing hard-won optimism. It's fitting that the movie climaxes with Zyric's story, in which we see nothing less than the dawning of a young man's social and political consciousness. I won't give away the thrilling tracking shot that ends the movie - except to say that even after the screen goes dark, you can still feel the camera hurtling forward almost as if it were still looking for its next subject. After passing the narrative baton from one character to the next, Green ends by passing it to us.

GROSS: Justin Chang is a film critic for the LA Times. Monday on FRESH AIR, we'll talk about the journalistic challenges of investigating Russian interference in the election and connections between the Trump campaign and Russia. My guest will be Washington Post reporter Greg Miller, who broke several related stories and shared a Pulitzer Prize this year. Now he has a new book called "The Apprentice: Trump, Russia and the Subversion of American Democracy." I hope you'll join us.

FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our engineer today is Adam Staniszewski (ph). We have additional engineering support from Joyce Lieberman and Julian Herzfeld. Our associate producer for digital media is Molly Seavy-Nesper. Thea Chaloner directed today's show. I'm Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.