Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on June 19, 2009

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20090619

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

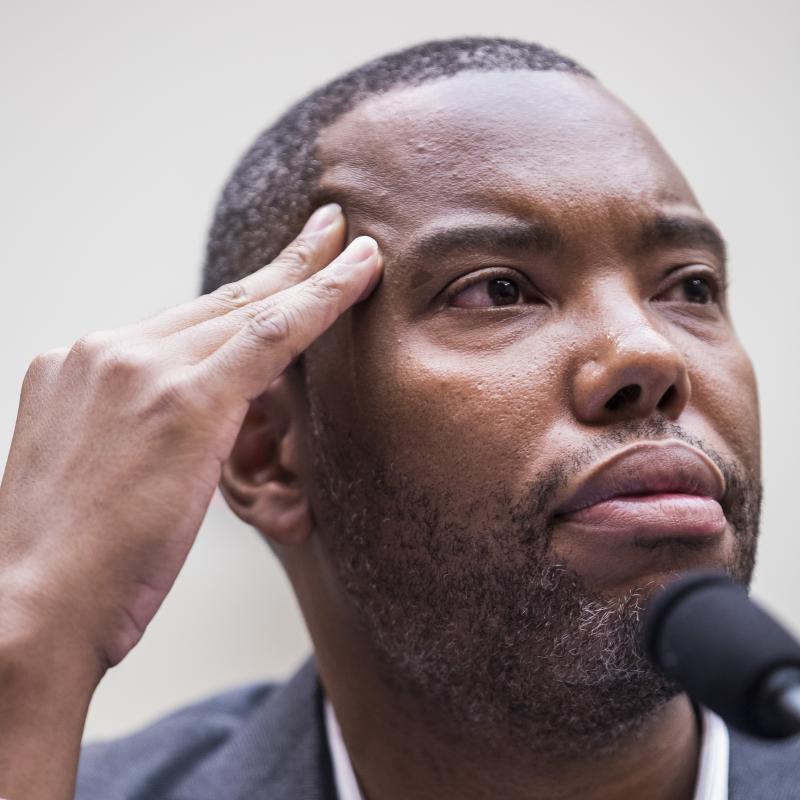

Ta-Nehisi Coates' 'Beautiful Struggle' To Manhood

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. Iâm David Bianculli of tvworthwatching.com, sitting

in for Terry Gross. Fatherâs Day is on Sunday, but why wait? Today,

weâre playing excerpts from some of Terryâs interviews that had sons or

daughters talking about their dads.

Weâll start with journalist and author Ta-Nehisi Coates. One of the

things that made Coates different from a lot of other kids in West

Baltimore, where he grew up, was that his father was a former Black

Panther.

His dad ran a small afro-centric publishing company called Black Classic

Press that was in the basement of the house. Upstairs, he presided over

a family of seven kids. Coates writes about his childhood in his memoir,

âThe Beautiful Struggle: A Father, Two Sons and an Unlikely Road to

Manhood.â

Coates is now a contributing editor and blogger for The Atlantic

magazine. His article about Michelle Obama was published in The Atlantic

in January, which is when Ta-Nehisi Coates spoke with Terry Gross.

TERRY GROSS, host:

You came from a very unusual home. Your father raised seven children

with four mothers, and they were all, including the four women,

considered your family. Would you describe the arrangement?

Mr. COATES: Yeah, well, the first to understand is it wasnât planned.

Thatâs the biggest thing. Itâs not like â and it certainly wasnât a

situation in which it was a polygamist household.

My dad was a young man. Being a young man, not necessarily always being

particularly careful, and Iâm quite thankful for that now, he had

relationships with four different women at various points, and in each

of those cases, there were kids yielded. In two of the cases, it was

multiple kids - with my mother, there were two kids. The first woman he

was married to, first wife, there were three kids.

My dad hated the term step-brother. He hated the term step-mother, step-

father, all that. We really didnât do that. He hated the term half-

brother. There were no halfs. We were raised to be really, really close,

and basically, most of the kids lived with their mothers for the most

part. If a kid was having trouble in school, particularly the boys were

going through hard times, my dad has five boys, they would come and live

with my dad. And my dad was, as many dads are across the country, the

disciplinarian who would get the kid back on track.

They would, you know come over on weekends. So there might be different

combinations of kids. It might be my sister Kelly(ph) and you know, my

sister Chris(ph) and me, or it might be my brother, Big Bill(ph) as he

was called at that time, My brother Malique(ph), my brother John(ph) and

me. It could be any combination of kids.

It was a very interesting thing. I have to tell you, though, I didnât

consider it particularly unusual because, quite frankly, there were a

lot of kids in the neighborhood who had a similar situation except in

most cases, the father was not there. And so I actually didnât

necessarily feel I was blessed, but I knew I was blessed.

GROSS: Did your father live in your home?

Mr. COATES: Yes he did, yes. I lived with my father all my life, until I

was 18, at least.

GROSS: Your father had been a Black Panther. Was monogamy one of the

institutions he was opposed to?

Mr. COATES: Yes, it was, very much so. And the Panthers had a sort of

doctrine of free love at that point, which I write about in the book. I

donât know how much my dad was, in his mind, opposed to monogamy when he

hooked up with my mother.

You know, child rearing was very important in my parentsâ relationship,

and I think it overshadowed romantic love. It was about getting those

kids together and getting them out of the house and making sure

everybody became productive members of society. And romantic love was

really, really secondary despite the fact that both of them had the

yearnings that all human beings have.

I donât know how much it was that my dad theoretically didnât believe in

monogamy at that point in time or that it just wasnât where he was, from

a romantic person, that he wasnât in love for most of the marriage.

GROSS: Your father published â had a small publishing company in the

basement and published books by African-American authors, afro-centric

books. Did you read those books growing up? Did they have an influence

on you?

Mr. COATES: I devoured them. I devoured all of them.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COATES: And you know, I felt - a way that I felt at the time and

later, you know, come back and questioned some of the stuff, at the same

time seeing the importance of having it out there.

At the time that I was coming up in Baltimore, crack had hit the city,

and guns had just flooded everywhere. I mean, Iâm talking about 10-, 11-

, 12-year-old kids with guns out on the corner selling crack. It changed

the temperature. It changed the volume. It changed how the city felt.

It was a much more violent city during the time that I was coming up.

And the thing you have to know about me is there was no religion in our

household, so there was no broader sense of what should explain where we

are. And I think just as a kid searching for answers, I was looking for

anything to explain what was going on, why young boys were being shot

over Starter jackets with the Philadelphia 76ers written across the

front, why, you know, a kid would come to school in a pair of shoes and

end up walking home in his socks because he got beat up, and somebody

took off his Air Jordans.

I didnât understand how it was that my world was like that, and yet you

would turn on the TV, and there was a completely different world,

obviously, out there were people had nice lawns, and you know, kids just

went to school. They didnât necessarily have to worry about any level of

violence.

I took to, quote-unquote, âafro-centric booksâ as a way to explain that

to myself. It was a kind of a mythology, a religion for me that

explained where I was, who I was and how I had ended up in that

particular space.

GROSS: At the same time, you also read a lot of comic books.

Mr. COATES: I did.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: You say my default position was sprawled across the bed, staring

at the ceiling or cataloging an extensive collection of âX-Factorâ comic

books. So how did your father react to you reading comics in addition to

you reading serious books, you know, what he would consider serious

books?

Mr. COATES: My dad had a position that kids reading was a good thing,

and you had to take kids where they were. You really, really did. I also

write in the book about how I played Dungeons & Dragons. Now you have to

â you know, knowing my dad and where he was in terms of black

consciousness, having a kid, you know, play a game that is based in, you

know, Tolkien and Norse mythology sounds like a weird mix, but in fact,

my dad appreciated the imagination that was inherent in the game. He

appreciated the sort of abstract level of reasoning.

There were a number of things that young black kids were doing at that

particular point in time that was not particularly healthy, and yet here

I was with my brother doing this, exploring a creativity.

My dad was very, very encouraging of that. Now we would have a whole â a

lot of conversations about how race and how race played out in those

particular worlds. But he never was, you know, a sort of people who was

like I donât want you playing the white manâs games or something like

that. I donât want you reading the white manâs comics.

That didnât really exist in my household. He was always very

encouraging. And the other thing that you have to understand about my

dad is when he was a kid, he collected comic books.

GROSS: Aha, okay.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. COATES: So that was key. That was key. And so there was, in fact, a

moment when I was younger, he talks about with my mom, you know, trying

to get me off of comic books and get me into more serious reading. He

said, you know, donât do that. Donât do that. You know, the boy is

reading. Encourage that.

GROSS: You said that your father would tell you, when you were on your

bed reading, that you had to go outside, that you had to â he said this

is your community. These are your people.

Mr. COATES: Right.

GROSS: What does that mean to you as, what I imagine, was a kind of

alienated teenager or preteen reading âX-Menâ comics at home?

Mr. COATES: I was very angry at him. I was very, very angry that he was

sending me out. Again, and this is, you know, just to put this

chronologically, this is at a period before I start reading, you know,

books about African-Americans for myself, as opposed to being assigned.

I didnât understand why my world was different. And moreover, I felt

like I had two parents, two really smart parents. I had a mother who

worked as a teacher. I had a dad who worked at Howard University. Why

were we living in West Baltimore? I didnât understand that at all. I

felt like if we could â you know, we were as good as anybody else. We

could live in the suburbs, have nice lawns, et cetera. This is my

thinking around 12 or so. Moreover, why do I have to go out and be

around kids who are of a different background than me? Now, hereâs a

lesson that my dadâ¦

GROSS: Kids who wanted to beat you up too, I might add.

Mr. COATES: Yes, yes, yes, some of them. Some of them - I developed some

great friendships, but yes, that was certainly part of it. Now my dadâs

thing was that he was raising men, as it came to me, for all seasons. He

wanted people who were comfortable in the neighborhood, people who were

exposed to things outside the neighborhood, people who could be

comfortable in many different worlds.

You know, he had a great, great feeling that despite what was going on

in the community, you could not â and I can remember my mother, in fact,

saying this all the time - you could not be scared of your own people.

You could not. Now, you had to be smart, you had to be safe, you had to

take certain steps, but you could not develop broad, big sort of

paintbrush ideas about black people.

GROSS: Did your parents live in West Baltimore, which was largely a

pretty poor community would you say? And you say the crack epidemic had

really spread there. Did they live there for political reasons as

opposed to economic reasons?

Mr. COATES: Yeah, I think, as a child, I interpreted it as political

reasons. I think it was partially political reasons, but it was, in

fact, at the end of the day, also economic reasons. I mean, we owned our

own house. It was, you know, a good house. My dad still owns it to this

day, and it wasnât particularly expensive for the time. And I should,

just to be very clear about where I was, you know, West Baltimore, like

any sort of broad area that gets painted as a ghetto, was actually quite

economically diverse.

So the area where we were was pretty much a working-class area. I would

not call it necessarily call it a poor area. We had Section 8 housing

and that sort of thing, but it wasnât like I was raised in the projects

or something like that. It wasnât that sort of situation.

Now, you canât insulate yourself from whatâs going on in the broader

community of West Baltimore and the city as a whole, but where I was

raised, there were not a lot of fathers around. But the mothers who were

there worked, and they worked hard.

GROSS: We talked a little bit about the neighborhood you grew up in and

the impact that had on you. Youâre raising a son now. What kind of

neighborhood are you raising him in? And did you consciously choose that

neighborhood to raise a son in, or did you just end up living there and

having a son?

Mr. COATES: Right. I live in Harlem. Iâm in Harlem, which again, itâs

tough to â people think of Harlem as a ghetto. Itâs very tough to

describe Harlem as a ghetto because itâs just so diverse.

I mean, there are folks like me who are college graduates there. There

are people who have been there all their lives. You know, just the other

day, I was doing some reporting. I was riding around with a gentleman

who lives in actually the projects of east Harlem who was working on

getting his son into an elite boarding school up in New England.

We drove up there and did that. So there are all kinds of people there.

Iâm a big fan of the diversity within the black community and sort of

bringing that out and myself, you know, exploring that as a writer.

I do want Samari(ph), my son, to have some sort of consciousness about

what it means to be an African-American. Now, thatâll change by the time

heâs, you know, as an adult, and heâll have to figure some of that out

for himself. But I donât want him in a situation, as I think sometimes

happens with certain people, in which he perceives African-Americans as

alien to him.

I donât want him learning about African-Americans from watching TV. I

donât even necessarily want him learning about African-Americans

strictly from listening to music. I want it to be a lived experience.

I think Barack Obama said something really great in the campaign. I

think about this always in regards to my son. He said: Iâm rooted in the

black community, Iâm not limited by it. And if I could do anything for

the kid, I mean, that would really be what it was.

GROSS: Well Ta-Nehisi Coates, thanks so much for talking with us.

Mr. COATES: Well, thank you for having me, Terry.

BIANCULLI: Ta-Nehisi Coates. His memoir, âThe Beautiful Struggle,â is

out in paperback. Coming up, comedian Carol Leifer on memories of her

father. This is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

105588797

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20090619

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Carol Leifer On Life, Comedy And Finding Love At 40

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. Out next guest on this special Fatherâs Day salute is

comic, actress and writer Carol Leifer, who got an early start in comedy

hearing her father tell jokes when she was a kid. She started working

the comedy clubs when Paul Reiser, Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David were

getting started, and they became her friends.

She later wrote for the NBC series, âSeinfeld,â and has starred in her

own TV comedy specials. Terry Gross spoke to Carol Leifer earlier this

year upon the publication of her memoir called âWhen You Lie About Your

Age, the Terrorists Win.â

TERRY GROSS, host:

Carol Leifer, welcome back to FRESH AIR.

Ms. Carol Leifer (Author, âWhen You Lie About Your Age, the Terrorists

Win: Reflections on Looking in the Mirrorâ): Thank you, Terry.

GROSS: Your opening essay in the new book is about your father, who

recently died at the age of 86, and you write that heâs the reason you

wanted to be funny because he was funny. And in this piece, you tell one

of the jokes that he used to tell. Itâs a, quote, âdirty jokeâ that you

didnât get when you were a kid. Itâs such a great joke, so I have to

start by asking you to tell it.

Ms. LEIFER: Okay, well a guy goes to the movies with his pet chicken.

And he buys two tickets and the person says, whoâs going in with you?

And he goes, well, my pet chicken here. And the ticket person says hey,

you canât bring an animal in the movie theater. So the guy goes around

the corner. He stuffs the chicken down his pants, goes into the movies,

and the movie starts, but the chicken is starting to get a little hot.

So the guy unzips his fly to let the chicken stick his head out and get

a little air.

So a little bit of time has passed by and a woman nudges her friend and

says, you know, this guy next to me just unzipped his pants. And the

woman goes eh, look, you know, youâve seen one, youâve seen them all.

And the woman goes, yeah, I know, but this oneâs eating my popcorn.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: I love that.

Ms. LEIFER: Yes, hilarity ensues, but I remember as a kid, you know, my

father telling this joke a lot and getting big laughs. And I was young

enough that I didnât really understand it, you know, because all I heard

was a chicken and, you know, a zipper, and it didnât really make sense.

I found out, you know, what the joke meant later, and that just might

have been the thing that pushed me into lesbianism, butâ¦

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Which weâll get to later.

Ms. LEIFER: Yeah, but I really â you know, my father was the king of the

joke-tellers. And I was so impressed as a child watching him hold people

in rapt attention with these stories and it had a big impact on me.

GROSS: So did he actually collect jokes?

Ms. LEIFER: He did. My father, he was the kind of guy that, you know,

heâd always say, throw out any subject and I got a joke on it. And he

really â one of the high points of his life was - my mom is a Ph.D. in

psychology and she went to one of her psychology conventions and the

scheduled entertainment for that night had cancelled. And the

psychologists, knowing that my father was a big joke-teller, asked if he

would mind stepping in and telling some jokes.

And as I hear it, you know, he was thrilled and delighted. And he I

think told about a half an hour or 45 minutes of jokes, and he killed.

And it was really a fantastic night for him. I think to my fatherâs

generation, to have a career in show business was not something that was

accessible or something that someone actually did, you know. And Iâm

really happy that he lived long enough to see a lot of my success and

was so happy for me. So itâs â you know, itâs nice that he left this

earth, you know, having seen that and shared that with me.

GROSS: When your father died, the family found a list of jokes that he

kept in his wallet. Did you know that he had that?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. LEIFER: I did know that he had that list of jokes. We all did, my

brother, sister and I, because you know, it ties back to that evening

that he entertained the shrinks at their convention. I know that he

thought if they ever asked him to perform again, he wanted to be

prepared. So he had his list of jokes there.

GROSS: So when the family was dividing up his possessions, you got the

paper with the jokes that you say you now keep in your wallet.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. LEIFER: Yes, I do keep it in my wallet. And if Iâm ever stuck at a

show, Iâm certain I will have no problem whipping it out and going

through the list. I - you know, I did a special many years ago. I think

I spoke about it the last time I was on the show, called âGaudy, Bawdy

and Blue,â which was a tribute to these bawdy, dirty comediennes of the

â50s and â60s. And I had asked my father to put on tape every dirty joke

he knew, and I think itâs about two hours worth of jokes. And Iâm so

happy that I kept it so that I really feel like I have my fatherâs

legacy with me because he wasnât a pro, but he had excellent timing.

He was an amazing comedian. And people who knew him, the first thing

they always said about him was that he was so funny. And I talk about

that in a piece that I think if my father knew that being funny was the

first thing that people said about him, that would be enough and make

him happy, not having had a professional career.

GROSS: What he did for a living, he was an optometrist.

Ms. LEIFER: Yes, he was, he was. But you know, he always shared funny

stories about, you know, being an optometrist. You know, people would

come in, and heâd say, heâd ask them, you know, can you please read the

eye chart? And they would ask, out loud? No, sir, you know, why donât

you mime it for us.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. LEIFER: Of course out loud. Or he would have people that would read

the eye chart and go capital E, capital F â you know, itâs like theyâre

all capitals, okay?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Ms. LEIFER: So yeah, we â I miss him so much.

GROSS: Now you pointed out that your father and his friends never

thought that a show-business profession was anything that was in reach,

but obviously you did and you did it. So what made you think when you

were young that it was within reach for you, that you could go, you

know, be a professional comic?

Ms. LEIFER: I think because I started so young, it was a dream that

seemed possible to pursue. You know, I started doing stand-up comedy as

a junior in college. You know, my mother had said, I thought it was

something that youâd get out of your system, you know. But I clearly

remember my father saying, you know, dad I passed the audition at this

comedy club and I want to transfer to Queens and try to become a

comedian.

My fatherâs like, you know what? You got to strike while the ironâs hot,

and I think that was great advice. I think it was an opportunity not to

be missed. But I do think the fact that I had still finished my college

degree, that was important to my parents. And I think to my generation

of comics, it was within reach. I think to â certainly to my dadâs

generation, I remember asking him why he had never pursued it, and he

said well, you know, someoneâs got to make a living. And you know, that

generation, it was a really far-off dream and not within the realm of

possibility.

BIANCULLI: Carol Leifer, speaking to Terry Gross earlier this year. Her

memoir is called âWhen You Lie About Your Age, The Terrorists Win.â

Hereâs a great song Loudon Wainwright III wrote about for his daughter.

Iâm David Bianculli, and this is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

105586861

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20090619

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Jimmie Dale Gilmore: In Song, A Eulogy For Dad

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. Iâm David Bianculli in for Terry Gross.

For the second half of our Father's Day show, weâve got three musical

sons telling stories about their respective dads.

First up, Jimmie Dale Gilmore. Gilmore is a singer from West Texas who

writes songs that would be described as alternative country. But in

2005, five years after his father died of ALS, Gilmore recorded an album

of classic country songs called "Come On Back." It was dedicated to his

late father and featured songs his father loved, including one by Jimmie

Rodgers for whom Jimmie Dale Gilmore was named. Gilmore visited Terry in

the FRESH AIR studio in 2005. He brought his guitar, and also brought

guitarist, Robbie Gjersoe who accompanies him on the "Come On Back" CD.

GROSS: Welcome everyone to FRESH AIR. It's really a pleasure to have you

here. Jimmie Dale Gilmore, this new CD is dedicated to your father who

died a few years ago. I want you to start with a song, "Pick Me Up On

Your Way Down," and what did the song mean to your dad?

Mr. JIMMIE DALE GILMORE (Singer-songwriter, musician): Well actually it

represents and entire style that I really associate with him. It's just

old, itâs honky tonk dance music it's what it amounts to and it's a, it

is one particular one that he really loved. I just, I have this memory

of him just, you know, with his kind of head tossed back and with his

eyes closed just grinning when this kind of music was on.

GROSS: Would you play it for us?

Mr. GILMORE: Yes. One, two, a one-two-three...

(Soundbite of song, "Pick Me Up On Your Way Down")

Mr. GILMORE: (Singing): You were mine for just a while. Now you're

putting on the style and you never once look back at your home across

the track. You're the gossip of the town, but my heart can still be

found where you tossed it on the ground, pick me up on your way down.

Pick me up on your way down when you're blue and all alone, when their

glamour starts to bore you, come on back where you belong. You may be

their pride and joy, but they'll find another toy, and they'll take away

your crown. Pick me up on your way down.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. GILMORE: All right. That's the way we fake being the band playing

the song.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: That's Jimmie Dale Gilmore on guitar, and singing, Robbie Gjersoe

who's singing harmonies and playing guitar. And that song is from Jimmie

Dale Gilmore's new CD "Come On Back." That sounded really great. As I

mentioned before, the CD is dedicated to your father who died of Lou

Gehrig's disease. Did he introduce you to country music?

Mr. GILMORE: Oh yes. Yes, for sure. He was from my very, very earliest

memories that music was always pervasive. It was radio. We didn't have

phonograph until I was actually in high school.

GROSS: Wow. That's pretty late.

Mr. GILMORE: And we - but my dad - we always had the radio going you

know. And my dad played, so he'll be sitting around the house playing

his guitar along with the radio or actually, you know, sometimes playing

that with bands for dances.

GROSS: And you quote a great advertisement for a dance that he was

playing where apparently he was one of the first musicians in West Texas

to use a solid body electric guitar.

Mr. GILMORE: That's right.

GROSS: So would you describe that ad?

Mr. GILMORE: Yes. It said - at this time, when I was very small, we live

I Tulia, Texas from the time I was from the time I was, until I was

about five-years-old and - on a dairy farm. And my mom recently, you

know a few years ago found a little clipping from the Tulia Herald, a

little tiny ad that said, dance at the VFW Hall featuring - with the

Swingeroos, featuring Brian Gilmore and his electric guitar.

GROSS: That's great. This...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. GILMORE: It's was such a novelty.

GROSS: So did your father teach you guitar or did you learn that on your

own?

Mr. GILMORE: He taught me just a little bit. He actually, he taught me

how to play "Wildwood Flower." And, but I, the thing is that I fell in-

love with the acoustic guitar and my dad was an electric player, and I

never did, to my regret now, I never did really learn to play the

electric well. I can fumble through with it. But I just learned - my dad

taught me a tiny amount and then I kind of went off in the really more

in the folk and blues direction as I was learning to play.

GROSS: I want you to do another song from your new CD, "Come On Back."

And the song I'm going to ask you play is a Johnny Cash song called,

âTrain Of Love." But tell us first how you first heard Johnny Cash and

what he meant to you.

Mr. GILMORE: Well, I may have heard a few of his recordings on the

radio, a little bit. This was when I was very young. But my first real

memory of it was my dad took my sister and I to see Johnny Cash with

Elvis Presley. And I was about 12. I think she was about 10. And it was

a - I've often said that I suspect at that night completely determined

that...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. GILMORE: ...the rest of my - at think at - I think that was one of

those places where a little...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. GILMORE: ...a little deflection happened - that I loved that music

so much. I loved the both of them.

GROSS: Well I wish I was at that concert. It must've been really early

in their career, right after they both signed with Sun Records...

Mr. GILMORE: Yes. It...

GROSS: ...at that concert with Presley and Cash. Wow.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Well, would you do that song for us, "Train Of Love"?

Mr. GILMORE: Yes. I will.

(Soundbite of song, "Train Of Love")

Mr. GILMORE: (Singing) Train of love's a-comin', big black wheels a-

humminâ. Sweetheart's waitin' at the station, happy hearts are drummin'

oh. Trainman tell me maybe, ain't you got my baby. Every so often

everybody's baby gets the urge to roam. But everybody's baby but mine's

comin' home. Train of love's a leavin', leavin' my heart grievin' but

early and late I sit and wait because I'm still believin' oh we'll walk

away together though I might wait forever. Every so often everybody's

baby gets the urge to roam. But everybody's baby but mine's comin' home.

Mr. GILMORE: (Singing) Train of love's a goin' and I got ways of knowin'

you're leaving other people's lovers but my own keeps goin' oh. Trainman

tell me maybe, ain't you got my baby. Every so often everybody's baby

gets the urge to roam. But everybody's baby but mine's comin' home.

Every so often everybody's baby gets the urge to roam. But everybody's

baby but mine's comin' home.

BIANCULLI: Jimmie Dale Gilmore visiting Terry Gross in the FRESH AIR

studios in 2005. The CD, dedicated to his father is called, "Come On

Back."

In a moment, we'll come on back with another country music father-son

story about Darrell and Wayne Scott. This is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

105599073

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20090619

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Wayne And Darrell Scott: Father-Son Country

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

Here's another musical father-son story for Father's Day. Darrell Scott

is an alternative country singer-songwriter who won an ASCAP Songwriter

of the Year Award in 2002 and plays with Steve Earle's Bluegrass Dukes.

Darrell's father, Wayne, is in his 70s and installs chain link fences.

When Darrell Scott became successful enough with his country music

career to start his own record label, the first thing he did was pay

tribute to his father. He produced an album of Wayne Scott singing

mostly his own songs, the songs that Darrell heard his father sing when

he was growing up. The album is called "This Weary Way." Terry spoke

with Darrell Scott and his father, Wayne Scott in 2006.

GROSS: Darrell Scott, Wayne Scott, welcome both of you to FRESH AIR,

pleasure to have you here. Darrell, when you started your record

company, the first album you released was by your father.

Mr. DARRELL SCOTT (Singer-songwriter): Mm-hmm.

GROSS: Now you know you're pretty well-known in the world of country

music.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: So why did you want your first record to be your father's music?

Mr. D. SCOTT: Well I just thought it was important. His music is

important. I know I'm his son and all that and there's that going for

it, but I really feel that his music is important just because itâs so

pure and true, especially to the form of really country music or

mountain kind of music. And I just, I heard these songs all my life and

I know them backwards and forwards and it was just time to finally get

him to come and record these you know with a bunch of my friends here in

Nashville or in some cases, we went to him up in Kentucky in his living

room and it was - I just thought it was time.

GROSS: You said that you used to think that all the songs he sang were

by Hank Williams, and Johnny Cash and other venerated songwriters. When

did you realize a lot of those songs were his own?

Mr. D. SCOTT: Well yes, they kind of blended together because around the

house he would do all of that. He'd do Johnny Cash, and Hank, and Merle

Haggard and all that, and his own. And there was a time where I didn't

know which was which. It was just all blended in as what I thought were

great songs. I'd say probably somewhere in my mid to late teens I

started catching on that okay, that's the Hank stuff and there's the

Johnny Cash stuff and really starting to see his songs which were his.

And actually it took - there was one song which is the title of the

record, "This Weary Way," I didn't know that that was not a Hank

Williams song until my late 20s. It just seemed so perfectly Hank in

terms of style, in terms of structure, and that might be my, from my

opinion, my dad's best song. So that's one that took me an extra 10

years...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SCOTT: ...to figure out that it wasn't Hanks.

GROSS: Wayne Scott, why didn't you make it more clear to your sons that

you were writing songs?

Mr. WAYNE SCOTT (Singer-songwriter): I decided to try to be a singer

instead of a writer. I've tried write - singing my songs once and I

didn't like the cold feet and cold shoulder I got singing them.

Mr. D. SCOTT: And he's talking about a club. I mean we used to play

clubs like when I was a teenager.

(Soundbite of laughter)

MR. D. SCOTT: So he's talking about a night playing in a bar you know

where they come to dance and drink and play five sets a night as far as

the band is concerned. So that's what he's referring to, you know, that

he did his songs one night and you know, of course, they wouldnât know

the songs and wondering why he's not doing you know the top 10 of the

country music at that time. So I think that was his brush with...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. D. SCOTT: ...trying out new you know, his material out in public.

And he take...

GROSS: Did you give up after one shot at it?

Mr. W. SCOTT: Yes.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. W. SCOTT: I never done it again.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. W. SCOTT: Now that's all I do and it's great. I'm glad that he

talked me into doing it and I'm, it's a new experience to me and people

actually listen to me too.

GROSS: Well youâve very generously offered to perform a duet for us, so

I'd like to ask you to do a song that Wayne Scott, you do on your CD,

and itâs called, "Sunday With My Son." And itâs a song that you wrote.

Let me ask you to tell us what you're talking about in the song. It

seems to be a song that directly comes out of your life.

Mr. W. SCOTT: Every word of it's the truth. That's the only way I can

write. I only have inspiration. I don't have no education. Not that it's

a gripe.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. W. SCOTT: I chose it. But, my son was - the youngest one - I hadn't

seen him in a long time and I had him one Sunday afternoon for three

hours. And we chose - I just love nature so we went out into the woods

to gather leaves and pinecones and things like that. And it was so

beautiful. The song started going and I had to keep turning my back to

him to not let him see the old man crying. And I come up with that song.

So by the next morning I had (unintelligible) of it and it said exactly

what I wanted it to say and this is it.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: So...

Mr. W. SCOTT: Do you want to hear it now?

GROSS: I absolutely want to hear it now. Yes.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. D. SCOTT: That's right.

Mr. W. SCOTT: Okay.

Mr. D. SCOTT: One-two...

(Soundbite of song, "Sunday With My Son")

Mr. W. SCOTT: (Singing) As I look back on some better years and things

don't mean a thing. Like chasing women, writing songs, riding trucks and

old freight trains. When I reach back for happy thoughts of things Iâve

done, one thing that I remember most is a Sunday with my son.

(Unintelligible) truth and honesty and this I kept remembering as we

gathered autumn leaves. When memory feeds up on the past of things that

Iâve done, one thing that I remember most was a Sunday with my son. I

fill his heart with happiness the way that he fills mine, but he just

canât make up 10 lost years in just three hours time.

Reflections call for happy thoughts when it does what Iâve got one, one

thing that I remember most was a Sunday with my son. (Unintelligible)

truth and honesty. And this I kept remembering as we gathered autumn

leaves. When memory feeds up on the past of things that I have done, one

thing that I remember most was a Sunday with my son. When memory feeds

up on the past of things that I have done, one thing that I remember

most was a Sunday with my son, Sunday with my son, Sunday with my son.

GROSS: Oh, thank you for doing that. Thatâs Wayne Scott singing and

playing on guitar and his son Darrell Scott accompanying him on banjo.

And Darrell, thank you for bringing your father to our attention.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. D. SCOTT: Absolutely, truly my pleasure.

GROSS: By recording him and pushing him, pushing him forward like that.

Mr. D. SCOTT: It's truly my pleasure.

GROSS: So, Darrell, you are â you have actually been able to make your

career in music both as a performer and as a songwriter. I mean as a

song writer you've had a several hits on the top of billboard country

chart.

Mr. D. SCOTT: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: Watching your father when youâre growing up, watching him perform

but making a living all kinds of other ways, from working in the steel

mill, I think, andâ¦

Mr. D. SCOTT: Mm-hmm. Steel mills and fence construction.

GROSS: Fence construction.

Mr. D. SCOTT: Filtering oil and all sorts of things.

GROSS: And moving around the country. So watching him do that and just

kind of playing on the side, did you think, well, me, I want to really

play professionally and make my life playing?

Mr. D. SCOTT: Yeah, I think I kind of knew that even as a kid. It just

was, I wouldnât say easy for me but it came naturally. It was like a

natural thing for me to gravitate towards and to play and because I grew

up in a family band. My dad of course played and sang and wrote. And I

had older brothers who played and younger brothers and, you know, itâs

just what you do as a family, have some - camping or fishing or into

baseball or whatever. And our thing really was to play music, and so I

was kind of, you know, online for that, really from the age of six I

started playing.

And you know, because our family business was fence construction, which

is really hard labor out in the sun kind of thing - I also learned, you

know, at about 11 or 12 that it was better for me to stay home, and

while the others were working, you know, someone needed to answer the

phone and cook. We were a bunch of bachelors. Basically my brothers and

I lived with my dad. And so I was the cook and so I found a way to get

out of hard labor actually pretty early.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. D. SCOTT: And I just kind of kept that up. Iâm still not into hard

labor.

GROSS: Wayne Scott, when your sons were born, did you look at them one

by one and think this is going to be my band?

Mr. W. SCOTT: Yeahâ¦

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. D. SCOTT: He absolutely did.

Mr. W. SCOTT: They are Ds.

GROSS: Yeah, all your sons. Their names all started with the letter D.

Why is that?

Mr. W. SCOTT: Yeah, that was for that reason, and they'reâ¦

GROSS: What, so you could start a band with them?

Mr. W. SCOTT: Yeah. And that their introduction to music was when they

come home I laid them in the bed and stood over them and played Hank

Williams, Johnny Cash, played with them about an hour or so. So you

wouldnât wake up when you heard me singing it to them in the morning

(unintelligible).

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. D. SCOTT: We were used to it.

GROSS: Thatâs funny.

Mr. W. SCOTT: They can sleep right through country music or they can

play it. Darrell, you knew he was a musician Iâd say at three. Well, all

the boys are professional, but Darrellâs the best. I mean, he â if itâs

got strings on it, he can play it. And at three years old, it was vivid

that he wouldnât be no fence builder.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: So how did having sons whose names each start with the letter D

help you in playing music or creating a band? I mean, I don't get that

part.

Mr. W. SCOTT: I was going to name them the two Ds, three Ds, four Ds, or

however many Ds it took, I said they're all going to be Ds, you know?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. D. SCOTT: So (unintelligible) the four Ds, five Ds, yeah.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. W. SCOTT: Thatâs the way it came. And honestly, that was the reason.

I was determined theyâd been musicians.

GROSS: Well, I want to thank you both so much for talking with us, thank

you.

Mr. W. SCOTT: Thank you.

Mr. D. SCOTT: Thanks, Terry.

BIANCULLI: Wayne Scott and his son, Darrell Scott, speaking to Terry

Gross in 2006. The fatherâs album, produced by his son, is called âThis

Weary Way.â Coming up, another musician, Branford Marsalis talks about

his father. This is FRESH AIR.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

105654880

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20090619

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Branford Marsalis: On Jazz Fathers And Sons

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. Weâre concluding our Fatherâs Day salute with jazz

saxophonist Branford Marsalis, brother of Wynton and son of the great

jazz pianist and teacher Ellis Marsalis. As a kid, Branford spent more

time listening Elton John and Led Zeppelin than he did checking out the

music that his dad was into. But Branford now has a long string of jazz

albums to his name as well as some genre-busting efforts including his

group Buckshot LeFounque, which combines jazz and hip-hop. In the pop

world heâs performed with Sting, The Dead and Bruce Hornsby, and for a

few years led Jay Lenoâs âTonight Showâ band. Terry spoke with Branford

in 2002.

TERRY GROSS: You grew up in what is now Americaâs probably most famous

jazz family - the Marsalis family. Your father, Ellis Marsalis, is a

pianist. When you were growing up, liking the music that you liked, did

you feel about his music the way, say, I felt about my fatherâs old

Benny Goodman records?

Mr. BRANFORD MARSALIS (Singer): I felt about my fatherâs music the way

that my next-door neighbor felt about his father the chauffeur driver.

That was just what he did.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. MARSALIS: How did you feel about you fatherâ¦

GROSS: Oh yeah (unintelligible) I really disliked them until about much

older, till in my 20s, anyways.

Mr. MARSALIS: Jazz is not for kids. You know, thereâs an argument. My

brother says jazz can be for kids. I donât think - jazz has a level of

sophistication thatâs just too hip for kids. It's not a music for kids

and it certainly wasnât the music for me. But it wasnât like heâd

playing and Iâd go, arrhhh! I would just leave the room.

GROSS: You just didn't care.

Mr. MARSALIS: I turned on the television in the other room until it was

my turn to listen my music and then I play on Cheech and Chong and Elton

John and James Brown and whatever I wanted to put on. And my father

would stay out, and then when James Brown came on heâd come in and say,

yeah kid, yeah Jack, I like that.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARSALIS: And he would always dance to it. When he danced to it he

would snap his fingers on two and four (unintelligible).

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Thatâs great. Yeah, yeah.

Mr. MARSALIS: âCold Sweat'sâ going on, you know.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. MARSALIS: (Singing) Like a cold sweat down, duh duh duh.

(Speaking) My fatherâs going, yeah. Da-da-da-da-di-da. And Iâm, no dad.

Just funny.

GROSS: (Unintelligible)

Mr. MARSALIS: Oh yeah, it was classic, it was classic.

GROSS: Oh, great. So - what was your first instrument?

Mr. MARSALIS: My first instrument was the piano. And then when I was a

freshman, when I was in the first grade or second grade, went and

started playing the trumpet. And I wanted to play an instrument. So I

said I want to play the trumpet. And my father says, no, weâre not going

to have two people playing the same instrument in the same household. So

you have to pick something else. Okay, clarinet. Okay, fine, you get the

clarinet. And I played the clarinet for seven years until I was a

sophomore in the high school and then I switched to the alto saxophone

because I wanted to be a funk band.

GROSS: Yeah, thatâs the thing. There are no clarinets in funk bands.

Mr. MARSALIS: If there were, it would be really bad.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARSALIS: It wouldnât work. It wouldnât be a good vibe at all.

GROSS: So tell me, is your father, has your father been really pleased

over the years that youâve come to love jazz and play it?

Mr. MARSALIS: Now he does. But my whole career to him is just one -

because my dad is, he has two words. I mean he always said, in typical

for Ellis Marsalis fashion (unintelligible) because he went into

concrete sequential and youâre a random abstract â I actually named a

record âRandom Abstract.â

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARSALIS: I said, whatâre you talking about, man, just talk to me

like Iâm your son. Whatâs this concrete sequential crap, you know?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARSALIS: And he went through it, you know, Winton does things like

A,B,C,D,E,F, and youâre like A,F,B,Z. And he just didnât understand that

because if you have that really - he is the concrete sequential.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. MARSALIS: So it just seems like - it seemed just rampant, just like

a pell-mell kind of thing, like what in the hell is he doing? I mean, I

just confused the hell out of my poor dad.

BIANCULLI: Branford Marsalis, speaking to Terry Gross in 2002. He

concludes our special Fatherâs Day salute. So on behalf of fathers

everywhere, and of daughters and sons who love them, Happy Fathers Day

this weekend.

You can download podcasts of our show at freshair.npr.org.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

105657986

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.