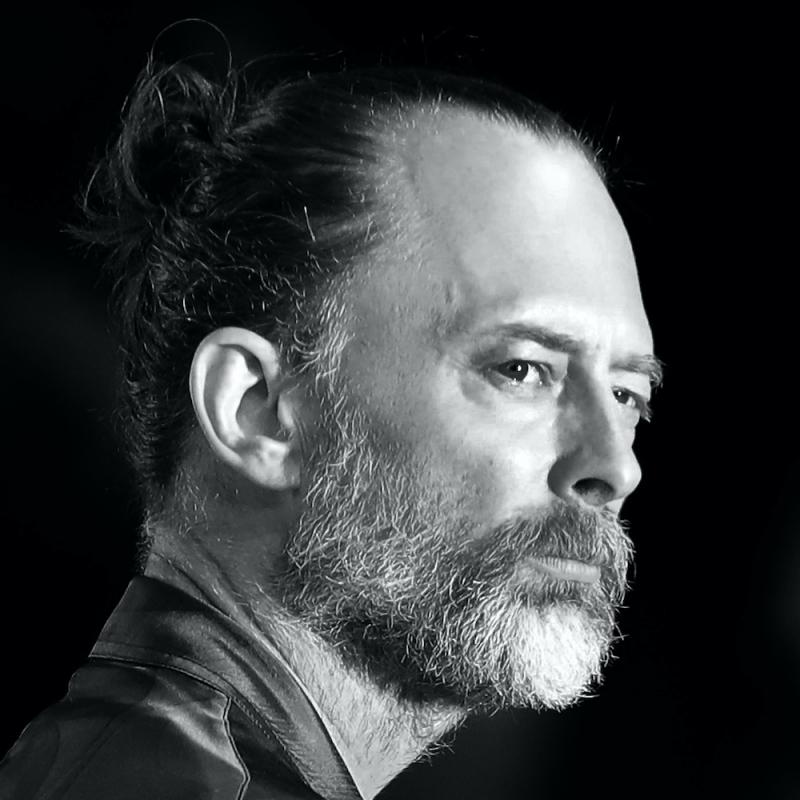

Thom Yorke, Going Solo

Thom Yorke is the lead singer and songwriter of the band Radiohead. Along with their longtime producer Nigel Godrich, Radiohead has released six critically acclaimed records and explored the boundaries between rock and electronic music. Yorke's new solo CD, The Eraser, is his first release without the band.

Other segments from the episode on July 12, 2006

Transcript

DATE July 12, 2006 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Thom Yorke of Radiohead discusses his career and

music

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

When rock critics write about the British band Radiohead, they often use the

words "best" and "greatest." A review in Time magazine was headlined

`Radiohead may just be the best band in the world.' Last year Spin magazine

named their album "OK Computer" the top album of the past 20 years.

Radiohead's last album, "Hail to the Thief," came out three years ago and

during that time the band's contract with their label ran out. They've been

trying out new material on the road the past few months and deciding if

they're going to sign with a major record company or distribute their music

themselves. This week, Radiohead singer Thom Yorke came out with an album

called "The Eraser," which he and the band's long-time producer Nigel Godrich

made largely on computers. Thom Yorke stopped by FRESH AIR for an interview.

Let's start with Radiohead's first hit. From 1993, "Creep."

(Soundbite from "Creep")

Mr. THOM YORKE: (singing)

I wanna have control

I want a perfect body

I want a perfect soul

I want you to notice

when I'm not around

You're so...(censored by network)...special

I wish I was special

But I'm a creep.

I'm a weirdo.

What the hell am I doing here?

I don't belong here, ohhhh, ohhhh.

She's running out the door

She's running out

she's run, run, run, run...

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Radiohead, "Creep."

Thom Yorke, welcome to FRESH AIR.

Mr. YORKE: Hi.

GROSS: When you recorded that, what kind of future did you think the band

had?

Mr. YORKE: Whoa. I had no idea what I was doing or no idea about the future

at all. That was the first vocal I ever did where I was--I came out at the

end of it and thought, `Oh, OK. I could do this for a living, perhaps.'

GROSS: You know, the lyric is, `You're so expletive special, I wish I were

special...

Mr. YORKE: I didn't really think...

GROSS: ...but I am a creep.'

Mr. YORKE: I didn't really think about that at the time. Not expecting

anyone to to play it.

GROSS: What was your life like when you wrote that song? And, you know, the

lyrics suggests somebody with low self-esteem.

Mr. YORKE: It was very hip around then. It was kind of written when I was

at college. I mean, we'd only just signed like a few months before that, I

think.

GROSS: Well, you met the other people from Radiohead when you were in high

school, right?

Mr. YORKE: At school, yeah.

GROSS: I just, like, it's amazing that you stuck together for so long, I

mean...

Mr. YORKE: I constantly think...

GROSS: That's remarkable.

Mr. YORKE: ...it's amazing.

GROSS: And part of me, like, after high--people change so much after high

school.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. Yeah.

GROSS: Have you changed in different directions and managed to stay together

in spite of that?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. I don't know how. I mean, one of the biggest challenges

recently, staying together, was actually having family and like having real

lives outside work. But I think we're kind of through the worst of that

really. It's actually kind of cool now. There's a strange shift in the

general dynamic of things, really, because you have to like reassess your

day-to-day existence, basically like every parent does.

GROSS: When you first started playing as a band when you were in high

school...

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: ...what were you playing? Were you playing original songs? Were you

doing covers?

Mr. YORKE: I used to, oh, well, we didn't really do, I mean, we didn't

really do much at school. I mean, we talked about it a lot and we endlessly

rehearsed, but we never really played any shows.

GROSS: What were you rehearsing? I mean, what kind of music was it?

Mr. YORKE: We were really into REM and, well, I mean, everyone was into

different stuff. Phil was a punk freak, and Ed was a Smiths freak, Jonny and

Colin were into Joy Division and the...(unintelligible).

GROSS: And you?

Mr. YORKE: I was the REM guy.

GROSS: You were the REM guy.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: Right. OK. What did music mean to you when you growing up?

Mr. YORKE: I came to it really quite late actually. I managed to--we didn't

have any music system in my house till I was eight, nine. And I think,

naturally enough, it started making a lot of sense when I hit puberty, which I

did fairly early. And then music was absolutely everything to me and has

remained so ever since.

GROSS: Well, I'm going to jump ahead to another CD. This is "OK Computer."

Mr. YORKE: Oh, OK.

GROSS: So this was like a huge success for you. Didn't it like go to number

one on Billboard charts?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. I'm not sure how that happened. I think it was something

to do with the record company but that may be me being cynical really.

GROSS: What do you think of as different on this CD from your preceding work?

Mr. YORKE: When we did "The Bends," we were really still figuring out, I

think, the basics even of how to make records. And in the process of doing

that we met Nigel, who was the engineer on it, who then went and did "OK

Computer" with us and has stayed with us. And then when we did "OK Computer,"

I think the difference was that it was like the kids being let loose in the

lab, you know. That's how it felt. I mean...

GROSS: What were you trying that you hadn't tried before?

Mr. YORKE: Well, we bought all our own equipment from some of the proceeds

from "The Bends." And it was transportable and so it, you know, the equipment

and the concept of recording became part of the creative process rather than

something that was happening in another room over there and we were just told

to do it again. So we were trying everything we could think of really within

limits. I guess since then that's got a little bit out of hand.

GROSS: So were your musical tastes changing at about this time?

Mr. YORKE: Well, it, I mean, they, you know, they're always changing, and

we're always listening to different things. One of the most important things

about being in a band, other than just playing together, obviously, is

actually what music you're sharing, what music you're choosing to play to each

other. And around that time there was this series of Enya, Marconi obsession

going on in the band, which really obviously fed, of course, into the way we

were recording.

GROSS: And yet there's no whistler?

Mr. YORKE: No, but there's a lot of pathetic attempts to sort of do similar

sort of things. You know, we bought an old Mellotrone and, you know, we're

using lots of those sort of soft distortion like old, you know, deliberately

trying to sort of emulate old recordings, which Nigel is especially good at.

GROSS: Mm-hm.

Mr. YORKE: Old recording techniques and stuff, you know.

GROSS: Well, the track I thought we'd play from "OK Computer" is "No

Surprises."

Mr. YORKE: Uh-huh.

GROSS: Do you want to say anything about writing this?

Mr. YORKE: Well, that's one of the songs that we refer to a lot because,

just in terms of when we're in the midst of a song and we don't know whether

we're just completely wasting our time. And "No Surprises" was like that all

the way through. It was just, `I don't know, I don't know about this.' I

mean, yes, it's a beautiful song, but it just seemed to be too much, too much.

And then gradually sort of chipping away at trying lots and lots of different

things. And then, it's amazing how as soon as you just got a little bit of

distance from it, as we were finishing the record and placing it in the

record, at how powerful it was really considering how difficult it was to

make. The nice thing about it, I think, is that you kind of forget about all

of the hard stuff. You forget about how difficult it is to do things.

Nigel's very fond of reminding me of that.

GROSS: On "No Surprises"...

Mr. YORKE: Mm.

GROSS: ...was there anything that--any moment where you realized, `OK, this

is actually a good track. This works.'

Mr. YORKE: It was, as often happens, it was actually sort of finally getting

a vocal that made sense, because it was so slow and we had to do sort of--we

ended up, we physically couldn't play it that slow. So it's--we used the old

Beatles technique of record it at the natural speed you want to play it at and

slow it down, and get this sort of strung-out effect. And then singing to

that was a really quite a weird experience.

GROSS: Wait. So you slowed down the instrumental track?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. Yeah.

GROSS: With...

Mr. YORKE: We recorded everything and then slowed it down, and then I sang

to it.

GROSS: Oh, I didn't realize that.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. I mean, you can hear it. You can hear it in some of the

words, especially where the drums play. And this is what they used to do with

Ringo all the time. That's why his fills used to--God, I'm Beatle obsessive.

Sad, but true. That's right. Yeah, they used to get the most amazing drums

fills on those Beatles records. They used to make them play lots faster and

then it would sound really strung out.

GROSS: Now, is the pitch different though, if you...

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: If they're playing on a pitch and then it's slowed down, it's going to

change the pitch.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: So does that, as the singer who's trying to sing...

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: ...on key with the record, put you in a strange position?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, but, you know, being in constant pitch has never been a

problem for me. I mean, as I have no idea what it is. So, you know, I just,

it doesn't matter if it's a little bit out of tune.

GROSS: All right. Well, let's hear the results. This is "No Surprises" from

"OK Computer."

(Soundbite of "No Surprises")

Mr. YORKE: (singing)

You look so tired-unhappy,

bring down the government

they don't, they don't speak for us

I'll take a quiet life,

a handshake of carbon monoxide

with no alarms and no surprises

no alarms and no surprises,

no alarms and no surprises

Silent silence.

(End of Soundbite)

GROSS: That's "No Surprises" from the Radiohead album "OK Computer," and my

guest is Thom Yorke.

Mr. YORKE: Hi.

GROSS: I'm wondering if--I've read this and I know it's no secret that you've

had--

Mr. YORKE: I have no secrets.

GROSS: ...an issue with depression...

Mr. YORKE: Oh, right.

GROSS: ...over the years.

Mr. YORKE: Oh, that secret.

GROSS: That secret, yes. So how do you think that has affected you as a

songwriter, a singer? Just in terms of like, you know, your subject matter or

your tempos, or, you know...

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: ...the kind of mood you're going for?

Mr. YORKE: I think it's most--both destructive and highly creative. And in

some ways it's a blessing because when you're in the midst of it, you hear

things and see things in a different way. I mean, actually, some people do

literally see things in a different way. Some people, the things actually do

actually get darker and sounds actually change and blah-blah-blah. And I find

that it's, in a way, it's, you know, my brain is set to receive other things.

And, you know, the trouble with it is really that it's debilitating as well

because you haven't any--you don't have energy. You don't have--in order to

do--especially in a band, actually, but just generally to be creative, you

need to have a lot of energy. You can't just, you know. And so you can be

extremely negative unnecessarily.

And I think over the years as I grew older and got gray hair, I realize that

there's times when I just have to sort of like chill out and go away, and sort

of just get my head straight. So it's just about dealing with it and managing

it now, which is good, you know. Ultimately it's a good thing.

But it's really not a big deal but at the same--I mean, I choose to talk about

it publicly because I've always had a problem with the fact that people call

our music depressing because it's like, `What, you don't get depressed? What,

your whole life is roses, is it?' You know, that's to me is like, `You are in

denial and you are the one with the problem.' I mean, I, yeah, I want to go

out. And I listen to disco music, I go, you know, I do this stuff, but it

just so happens I'm built to do this. This is what I do. I mean, that's

fine. But, you know--and I think that's why I, you know, that was why I chose

to make a thing out of it, because it was just really annoying me.

GROSS: My guest is Thom Yorke of the band Radiohead. He has a new solo CD

called "The Eraser." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Thom Yorke of Radiohead. His solo CD "The Eraser" was

released this week. When we left off, we were talking about dealing with

depression.

I know that after or during the "OK Computer" tour, which ended up being like

a really long tour, and it sounds like you had real trouble toward the end of

it. That...

Mr. YORKE: That was just a general madness going on, and it started out as

being fun. And then it ceased to be fun and ceased to be relevant to the

music. People started projecting all this...(censored by network)...onto me

which was just, `No, no, no.'

GROSS: People were projecting things onto you?

Mr. YORKE: Well, yeah. People would sort of, yeah, I mean, like when people

come up and start talking to you and, in a certain way, which is--I found

really disturbing, you know. I'm a musician. I sing songs. That's it. I'm

not taking any of this whatever weirdness you've giving me. It's not my

responsibility, you know. And suddenly there was this responsibility to live

up to this thing that was nothing to do with anything. I mean, you just--it

was some sort of feedback thing: feedback noise, media noise, blah-blah-blah,

you know, cultural crap. I don't really understand why exactly it was a

problem, but it was. I should, you know, I should have been enjoying it.

What happened ultimately was a good thing, you know. Ultimately it was really

quite amazing time.

GROSS: From what I read, it sounds like there were times on stage during that

tour when you...

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: ...when you were kind of unraveling.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, that was weird. I mean, I don't know quite why. I think a

lot of the shows were very big and it was not interesting, and mostly it was

just not interesting. It just got boring> Which sounds incredibly selfish

but, why would you just carry on just playing these tunes? I mean, you know,

the trouble with it was that by the time we'd done that record, we were so

sick of those tunes. And then you're faced with the prospect of like having

to play them for another year and a half, which, you know, you've got to do

because you've got to let people know what it's about. And one of the things

that we're good at is playing the tunes and blah-blah-blah. But, you know,

there just sort of comes a point where it's like this is--you're going through

the motions. And as soon as you realize, `I am going through the motions,

this is sounding tired.' That's it, you know? You--there is kind of no point.

This is--it's rock 'n' roll. There's no point in you being there. It's like,

it ceases to be rock 'n' roll and just becomes some sort of dodgy circus.

GROSS: So did you feel like you were basically forced into the position of

being phony because you were no longer feeling the songs with the same

intensity, and yet you had to play them as if you did?

Mr. YORKE: Well, that was the thing for me. I refused to still stand on the

stage and pretend I was really into it when I wasn't. So I would stand there

on the stage about half a minute looking out into the audience

going...(sighs)...`I'm not really into this.' Because that was me trying not

to be fake about it.

GROSS: But, of course, that's a real insult to the people who paid a lot of

money to come hear you.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. Except but it's like, but then, well, what do you want?

Do you want me to be genuine or do you want me to just pretend? Which do you

want, you know? The genuine thing for me to do at this point would just to

get on a train and go home.

GROSS: I want to play another track, and this is from the latest Radiohead

album. It's called "Hail to the Thief."

Mr. YORKE OK. Cool.

GROSS: And the track I want to play is "We Suck Your Blood."

Mr. YORKE: Right. "We Suck Young Blood." Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah. Oh, would you want to say anything else about this song?

There's hand claps in it and...

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. It's long. It's very long. The band says it's too long.

I still really like it, though. But anyway.

GROSS: This is--this really stands out as being like very different, I think,

than other songs you've recorded. They're just...

Mr. YORKE: Really?

GROSS: Yeah. I just think it's like a different...

Mr. YORKE: I mean, yeah. I really...

GROSS: Something.

Mr. YORKE: It's--I think the reference points, there was like a lots of

Bowie in that, which you probably can't hear. But lots of Mingus, as well.

That whole--my absolute favorite Mingus track is the first one on the "Town

Hall Concert." It's called "Freedom," "Freedom Part I." And it has that sort

of slow handle. It's like--it's the deliberate, sort of kind of slave ship

rhythm, you know, the tortuously slow, like the whip being cracked

to--whatever it is--the drum being hit. You know? That sort of thing that's

kind of what the whole vibe of it was really.

GROSS: OK. This is "We Suck Young Blood" from Radiohead's latest album,

which is called "Hail to the Thief."

Mr. YORKE: Mm.

GROSS: And my guest is Thom Yorke.

Mr. YORKE: Hey.

(Soundbite of "We Suck Young Blood")

Mr. YORKE: (singing)

Fleabitten, motheaten?

We suck young blood

We suck young blood

Won't let the creeping ivy

Won't let the nervous bury me.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Radiohead. Thom Yorke's new solo CD is called "The Eraser."

He'll be back in the second half of the show. I'm Terry Gross and this is

FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. We're talking with Thom Yorke of

Radiohead. The band was described by critic Jon Pareles as rock's most

experimental top 10 band. It's been three years since the band's latest

album, but Yorke has a solo album of his own that was released this week

called "The Eraser." Here's a track from it.

(Soundbite of music from "Skip Divided")

Mr. YORKE: (singing)

Without appropriate papers or permissions

I'm in a mighty tight situation

But then I head into your french windows

I thought there was this big connection

They only got my name

They only got my situation

I just need my number and location

The wall keeps telling me

Hey hey, hey hey

Hey, hey, The devil may

Hey hey, hey hey, hey hey

You are a fool, you are a fool

for sticking 'round, for sticking 'round

Yeah you are a fool, you are a fool,

for sticking 'round, for sticking 'round

I've tried every trick in the book

I've tried to look at...

(End of soundbite

GROSS: That's "Skip Divided" from Thom Yorke's new CD "The Eraser." Let's get

back to our interview with Yorke.

If you don't mind, I'm going to ask you a couple of questions about your eye.

Mr. YORKE: OK.

GROSS: I know when you were young you had five or six operations on your eye.

Mr. YORKE: Mm.

GROSS: And for what? What was the problem?

Mr. YORKE: Oh, it was shut when I was born. There was no...

GROSS: It was shut? The eye was shut?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. Which apparently, you know, happens quite a lot. Not that

much, obviously. But it is known to happen.

GROSS: So can you see out of your eye now?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, kind of. They kind of messed up the last operation, so

it's a bit messy.

GROSS: So did people give you a hard time because of your eye? Kids pick on

kids for anything that's different.

Mr. YORKE: One. Not really, y no. I was a bit psycho when I was a kid.

GROSS: Were you really? How was that expressed?

Mr. YORKE: Throwing other kids around and, you know.

GROSS: Really?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. So I wasn't any shrinking violet by any description.

GROSS: I want to play another track and this is from your album "Kid A."

Mr. YORKE: Rah.

GROSS: And I thought we could play "Idioteque."

Mr. YORKE: Hurrah. I like that one.

GROSS: And you got a real like electronic thing going on here. When did you

start getting interested in electronic instruments? And I've been really

wondering if you went back and listened to a lot of, like, the early

electronic avant garde music of say the '60s?

Mr. YORKE: I did actually. Yeah, when did I do that? I mean, I didn't

really know much about it until I guess I started really collecting it up and

during the band's "OK Computer." I mean, my--the things I was really, really

into at college was electronic music. I was massively into it.

GROSS: Like what kind? Were you...

Mr. YORKE: The Detroit techno stuff that was coming out, and I was

getting--criminy, I don't know what it was half of it, you know. And there

was all these--there was all this British answer to it, as well as the Warp

label and Sheffield. And they were coming out with just amazing stuff, I

mean, the reason it was amazing was because I was deejaying every Friday at

college. And the stuff that sounded the most exciting coming out of the

speakers was not the rock music. It was this minimal techno. It was just--it

just sounded fantastic coming out of your Technics 1200s that the needle is a

bit damaged and the speakers are kind of blowing up, and you've had a little

bit too much to drink and some twit is asking for the Pogues again. So you

just whack on like some Warp record really loud and just clear the dance

floor. But you were having the best time and that's--that was my sort of

formative thing, the electronic. It wasn't actually sort of craft work. And

I knew that was the reference point. And I had...(unintelligible)...but I

didn't know, you know, the real history behind craft work at all. You know?

I came to it all backwards as one does.

And then I got really heavily back into it after "OK Computer," because I'd

absolutely had enough of rock music, predictably enough, you know. I

didn't--I hadn't had enough of being in the band, but I'd had enough of those

sounds. I mean, like, I "OK Computer" was a very consciously acoustic record,

using acoustic spaces very, very deliberately, hardly using any fake reverbs,

using real reverbs, and real groove sounds, putting mikes in the wrong ends of

the room and all this sort of stuff.

We'd all read this--me and the Greenwoods anyway--we'd read this book on how

recording music had changed the way music was. And it was like this thesis on

different techniques and how actually writing music and recording music had

changed since it was coming out with speakers, and it wasn't live. And the

logical conclusion of this book was electronic music, to me, was it was like,

you know, if you put a microphone in front of something, and then you play it

out the speaker, there's all this extra distance between what's really

happening and you. And what was so exciting about electronic music was it was

like literally there's no distance between the music and the speaker. It's

just straight out the speaker. There's no nothing else there at all.

GROSS: Now I could see you being really interested in this and then you could

create this, you know, like, electronic environment that you could then sing

over.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: What about the guitarist and the bass player in your band?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, it was...

GROSS: How did they feel about it?

Mr. YORKE: It was a bit of a brain mash. They were definitely not into it

to begin with. But at the same time, you know, the recordings didn't really

end up like that. I mean, both "Kid A" and "Amnesiac" were lots and lots of

different stuff. There's been a bit of focus on, `Oh, that's when they went

all electronic.' Well, OK, you could say the first song on "Kid A" "Everything

in It's Right Place," is electronic. But, you know, we'd actually tried it

every other way and it didn't work. And that's how it worked. So that's

that, you know. It wasn't like, `Yes, now we are making electronic record.

You are either with me or against me.' It wasn't really like that but...

GROSS: What about with "Idioteque," did you intend for that to be electronic?

Mr. YORKE: "Idioteque" wasn't, I mean, this is the good thing about being in

a band. "Idioteque" wasn't my idea at all. It was Jonny's. Jonny handed me

this DAT that he'd gone into our studio one afternoon. And the DAT was like

50 minutes long. And I sat there and listened to this 50 minutes, and some of

it was just, `What?' But then there was this section about 40 seconds long in

the middle of it that was absolute genius, and I just cut that out and that

was it.

GROSS: And you wrote the song around it?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. And that's, to me, that's my most exciting time is when

someone just hands me something and goes, `Listen to this.` And it has nothing

to do with me, and I just respond to it immediately like that. I don't have

to pick up a guitar. I don't have to do this and this and this. It's just

there.

GROSS: Is that how you write a lot of the songs?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. It's still how we write. I mean, you know, obviously it's

still--it's fun crafting songs using chords and stuff. But when it's like

sort of found, like that. Like, you weren't there when it happened, you were

just given it. I find that really--it's a really pure sort of response to

whatever it is.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear "Idioteque" from "Kid A." This is Radiohead and

my guest is Thom Yorke.

(Soundbite of "Idioteque" from "Kid A")

Mr. YORKE: (singing)

Who's in a bunker?

Who's in a bunker?

Women and children first

And the children first

And the children

I laugh until my head comes off

I'll swallow till I burst

Until I

Who's in a bunker?

Who's in a bunker?

I have seen too much

I haven't seen enough

You haven't seen it

I'll laugh until my head comes off

Women and children first

And children first

And children

Here I'm allowed

Everything all of the time

Here I'm allowed

Everything all of the time

Ice age coming

Ice age coming

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Radiohead from their CD "Kid A."

So we were talking a little bit about your kind of electronic or

electronica...

Mr. YORKE: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...yeah, influence there.

Mr. YORKE: Yes.

GROSS: And you have a new solo CD. It's not Radiohead. It's a Thom Yorke

CD...

Mr. YORKE: That's right. Yeah.

GROSS: ...coming out soon.

Mr. YORKE: It's got my name on it, which is a bit weird.

GROSS: So you have a new Thom Yorke CD and that's very electronica...

Mr. YORKE: Yes.

GROSS: ...influence. So did you feel freer to head in that direction

without...

Mr. YORKE: I thought...

GROSS: ...without the other musicians?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, I wanted to do--doing electronic music is a very--or can be

a very mono experience. It's like you just sitting there and you're looking

at the computer, blah-blah-blah. I mean it's not fun for a group of musicians

to sit in a room and watch a screen. It's not very interesting really. And

if you work--well, I mean, in this case it was very much a collaboration

between me and Nigel. But when you're just sort of sitting there and there's

only two of you, there was very little discussion going on. You're just doing

it, which, you know, when it's electronic music seems to make quite a lot of

sense really. I mean, even that, I mean, that was the case when we were doing

"Kid A," as well. You know, a lot of the stuff on that was just, well,

there'd be one or two people involved. And it's just in this particular

instance we were taking a break and said, `I really wanted to just go off and

try doing something on my own. Just, I want to know what it feels like, you

know.' And everyone was cool with that.

GROSS: And how does it feel?

Mr. YORKE: It was--the coolest thing about it is it's really got my

confidence back, and I was suffering from serious lack of confidence at the

end of sort of "Hail to the Thief.'

GROSS: What, as a songwriter, as a singer?

Mr. YORKE: Everything. Yeah, about all that stuff.

GROSS: As a father, a man and a human being, too?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, that too. Absolutely. Yeah, you know, usual stuff.

And, yeah, it was just--it was something I was burning to do. I really,

really wanted to do it. And it was like, you know, when it came up I think

there was a sort of sense of relief that I was going to get it out of my

system, to be honest. Which doesn't mean--that doesn't necessarily mean like,

`Yeah, yeah, go off and do your techno record. Get it out of your system.' It

was like, `Whatever it is, just go and get it out of your system.' I mean,

that doesn't mean we're never going to do that stuff again either.

In fact, I think, one of the interesting things about it was just how, you

know, you have to work on intuition. And it was done very quickly and very

fast, and you get your sense of instinct sort of back and things, and I feel

that will feed well into working with the band. Well, it is doing already

really.

GROSS: On the first track of your new CD...

Mr. YORKE: Yes.

GROSS: ...it sounds like you did something to electronically process the

piano.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, it's called--it's called a...

GROSS: I'm wondering what you did.

Mr. YORKE: Well, I mean, that's just, I mean, those are Jonny's chords. I

sort of recorded them on the Dictaphone. I don't know if he ever remembered

me doing it.

GROSS: On a Dictaphone?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, like one of those 20 quid Dictaphones that you get and then

just processed it. Not much really. I mean, it sounded so bad anyway I had

to process it. But I couldn't--I had absolutely no idea what the chords were.

I couldn't emulate them so it was like, well, we had to use that. And then,

when we were sort of putting together the basic ideas that I'd got on the

laptop with Nigel--Nigel was--one of the things he responded to initially with

the ideas was the fact that it was kind of small sounding and it wasn't, you

know--it was--they were very--they were not elaborate. It was very sort of

out of a box, although there are some big sounds on there. I quite like the

fact that occasionally it just goes bang, and you get all those huge sounds

coming in, and then it shuts down again. It's kind of cool.

GROSS: Well, Thom Yorke, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. YORKE: Thanks, Terry. It was cool.

GROSS: Thom Yorke of Radiohead. His new solo CD is called "The Eraser."

Here's another track from it.

(Soundbite from "The Eraser")

Mr. YORKE: (singing)

Please excuse me but I've got ask

Are you only being nice

Because you want something

My fairy tale arrow pierces

Be careful how you respond

'Cause you'd not end up in this song

I never gave you any encouragement

And it's doing me in

Doing me in

Doing me in

Doing me in

The more you try to erase me

The more, the more

The more that I appear

Oh the more, the more

The more you try the eraser

The more, the more

The more that you appear

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's the title track of "The Eraser."

Coming up, Maureen Corrigan reviews the new novel "The Abortionist's

Daughter." This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Book critic Maureen Corrigan reviews "The Abortionist's

Daughter" by Elisabeth Hyde

TERRY GROSS, host:

Book critic Maureen Corrigan says that she's just read an odd new novel called

"The Abortionist's Daughter" by Elisabeth Hyde, whose mix of light-heartedness

and danger would be a perfect tonal match for those sunny, hot days at the

beach when you can't swim because jellyfish are in the water.

Ms. MAUREEN CORRIGAN: There I was in the local organic supermarket the other

day, when I had this odd flare of fury. I'd just finished loading my

groceries on the conveyer belt and had pushed my cart up to be closer to the

cashier, when a movement caught my eye, and I turned around. The woman in

back of me was touching my groceries. She'd obviously already nudged my olive

bread farther along the conveyer belt so that she could begin loading her

stuff. But I caught her in the act of lifting up my angel food cake so that

she could get a look of the ingredients label affixed to the bottom of the

plastic container.

I stared at her, and she smiled. `It looks good,' she said. `I hope you

don't mind.' I gave her a tight smile back because in fact I did mind.

Irrationally, I minded a lot, and the fact that I was experiencing this spurt

of grocery road rage while smack in the middle of this food store with its

slogans about "No Animal Testing" and "Saving the Rainforest" made the moment

all the more ludicrous.

Chalk it up to the heat or the fact that I'd just finished reading Elisabeth

Hyde's darkly witty new novel, "The Abortionist's Daughter." Mundane moments

of weirdness abound in that book, and after reading it, I felt that I was

under its off-kilter influence, that people around me were behaving strangely

by a degree or two, and so was I. From the title and the book jacket

synopsis, I'd expected a literary novel of ideas about the moral and political

conundrum of abortion. Instead, "The Abortionist's Daughter" accordions out

into a suspense story and a comic noire, a novel of manners and an improbable

romance. And when I'd finally got accustomed to this pattern of the

unexpected, the novel surprised me at the end by settling down and getting,

well, a little soppy.

The novel's first cued sentence gives fair warning that this is going to be a

wayward tale. Hyde writes, `The problem was Megan had just taken the second

half of the ecstasy when her father called with the news.' Megan is the

college-aged abortionist's daughter of the title and the news her father is

calling with is that her mother, Diana Duprey, a doctor who runs an abortion

clinic in a small Colorado town, has just been found floating dead in her

in-home exercise pool. It doesn't look like an accident. Diana had been the

target of plenty of death threats from anti-abortion zealots, but why, the

police want to know, would a woman who routinely wears a bullet-proof vest not

fix the lock that's been broken for days on her back door. More curious

revelations and red herrings emerge as the investigation proceeds. A young

cop and Megan fall in lust. Megan's father, the local DA, refuses to account

for his whereabouts for three hours in a blizzard during the time period that

Diana was murdered.

But it's really Hyde's zest for misbehavior, the inappropriate emotion, the

surprising word choice, that makes "The Abortionist's Daughter" so striking.

Here for instance is a flashback in which she describes Diana meeting her

daughter Megan's prom date.

`Diana eyed Bill up and down. She had delivered him into this world, actually

back before she opened the clinic. She'd also circumcised him, she recalled

now. Involuntarily, she glanced at his crotch.'

Or take this description of Megan's reaction to a key break in the case.

`She looked truly perplexed as though she'd switched on the radio midstory and

heard the word `assassination' or `smallpox.''

I'm still not quite sure what to call "The Abortionist's Daughter." Its

cockeyed sensibility and plot detours certainly carry it out of the realm of

both straight literary fiction or pure suspense. Like that annoying woman

behind me in the socially conscious grocery store, I find myself reflexively

picking up the book and looking for a label. Nothing organic in this literary

concoction. Rather, it's the heightened artificiality of its ingredients, the

way they don't mesh with each other, that gives this novel its distinctive

tang.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. She

reviewed "The Abortionist's Daughter" by Elisabeth Hyde.

Coming up jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews a new CD by a clarinet trio.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews "The Clarinets" album

from the clarinet-playing trio of Anthony Burr, Oscar Noriega and

Chris Speed

TERRY GROSS, host:

Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead says there are lots of good improvising clarinet

players all over the planet nowadays, working in jazz and out of it. There

have been records by clarinet trios, quartets and larger ensembles, but Kevin

says a new clarinet trio record stands out for what it does and doesn't do.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. KEVIN WHITEHEAD (Jazz Critic): Chris Speed and Oscar Noriega on

clarinets and Anthony Burr on bass clarinet, from their album "The Clarinets."

Together, the trio encompass a wide stylistic background. Chris Speed has

been in umpteen jazzy, rocky, Balkan style and in-betweeny bands in New York,

but began by studying classical clarinet. Like Speed, Oscar Noriega is a busy

Brooklyn improviser. But he started out in a Mexican band with his brothers

back home in Tucson, and he now plays in a hip downtown group that does

Charles Ives covers. He switches here between clarinet and bass clarinet, so

sometimes we get two low horns deployed against a high one.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. WHITEHEAD: Australia-born bass clarinetist Anthony Burr has played

complex chamber music by the likes of Richard Barrett, whose pieces are

informed by the sounds modern improvisers make.

Borders between genres get trampled all the time, but this trio shows how the

sounds of painstakingly composed and spontaneously improvised music grow

closer together. There's so much attentive interaction and so many pieces

develop one specific idea, these improvisations seem to spring from one mind.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. WHITEHEAD: The improvised music on the clarinets, which is on the new

Skirl label, is often notable for what it isn't. It's not sweet and lyrical

and swingy in a jazz clarinet kind of way. There are no melodies or pretty

harmonies to speak of. It's more about texture and slowly unspooling lines

that may spread from one instrument to another. The trio mostly stick

together. They revel in the interference pattern set up when all three horns

converge on a narrow range of pitches.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. WHITEHEAD: That glacial pace is typical of much of this music, at times,

so slow it's spooky. That does give the clarinetists time to make minute

adjustments in a long note's timbre or pitch. The result may sound less like

woodwinds than electronic music or feedback or running a wet finger around the

rim of a glass. The lack of vibrato, that human twitch, can play tricks on

your ears.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. WHITEHEAD: The CD "The Clarinets" is austere and devoid of frills, right

down to its cover, which sports a barely readable font you could mistake for a

new alphabet. The oversized format makes the sleeves stand out in a literal

way. The cover's even too cool to list the titles. For their part, the

players bypass useful strategies improvisers have developed to keep the music

flowing. Each avoids the temptation to break out on his own, to disrupt an

established pattern or trigger a fresh episode or just take a solo for the

hell of it. The amazing thing isn't just that they trust each other not to

blink. The amazing thing is nobody blinks.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Kevin Whitehead teaches English and American Studies at the University

of Kansas, and he's a jazz columnist for eMusic.com. He reviewed "The

Clarinets" by the clarinet trio.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.